Friday Freakout: Does Supporting School Choice Mean Hating Public School?

Does the Arizona legislature hate public schools? Arizona Republic columnist Laurie Roberts says it does. Her proof: Senate Bill 1434, which would expand eligibility for Arizona’s education savings accounts (ESAs) to include students on district and charter school waiting lists.

Under Arizona’s ESA law, the state takes 90 percent of the funds it would have spent on a given child at her assigned district school and, upon her parent’s request, deposits those funds in an account that can be used for a variety of educational expenses, such as private school tuition, tutoring, textbooks, online learning, homeschool curricula, and more.

So, how does supporting school choice through ESAs entail “hate” for district schools? According to Roberts, “SB 1434 is aimed at enticing more kids to leave public schools.”

Contrary to Roberts’ insinuation, these families aren’t like The Little Rascals following around a dollar on a string that’s being secretly pulled by school choice supporters. These parents were already seeking options and solutions. After all, the waiting lists existed before this expansion was ever proposed. ESAs are in response to parent demand.

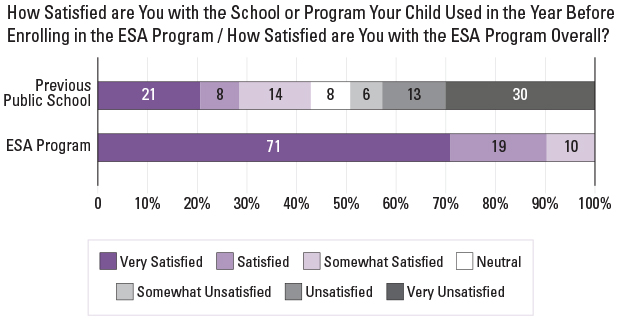

It should come as no surprise such families are more satisfied when they can choose the options that work best for them—especially when they can completely design their child’s education, which ESAs allow.

Currently, ESA eligibility is limited to students with special needs, students assigned to a district school labeled D or F by the state, foster children, and children of active-duty military personnel and those killed in the line of duty. SB 1434 would expand eligibility to include any child who “was previously denied admission to a district school or charter school that is operated within 25 miles of the child’s residence within the previous 12 months.”

Roberts fears allowing “virtually any parent” to “siphon money” away from district schools to customize their child’s education would effectively “dismantle traditional public education.” Her concern raises three valuable questions more states and communities should be discussing:

Question #1: Should public education support schools or students?

It’s the opinion of this and other school choice supporters that public education exists to fund the best possible education for every child, whether that’s at a district school, private school, parochial school, home school, or other service provider. And the evidence shows that model benefits students.

The conclusion of 13 out of 14 randomized controlled trials—the gold standard for social science research—is that school choice programs raise participating students’ academic performance, and increase their likelihood of graduating high school and enrolling in and graduating from college. One study found no statistically significant difference and none found any harm.It should come as no surprise such families are more satisfied when they can choose the options that work best for them—especially when they can completely design their child’s education, which ESAs allow.

In 2013, Jonathan Butcher and I conducted a survey of Arizona parents who were using ESAs to customize the educational experiences for their children with special needs. Whereas only 43 percent of the parents were satisfied with the district school to which their child had been assigned, an astounding 100 percent were satisfied with the education their child was getting with the ESA.

That said, Roberts has a legitimate concern about the potential impact educational choice laws have on the students who remain at their assigned district schools. It’s great if choice students benefit, but do their enrollment decisions harm others?

Question #2: Does school choice harm district schools?

One oft-repeated concern about school choice is that—in the lexicon of the great developmental economist Albert O. Hirschman—granting families an “exit” option would come at the expense of using their “voice” to improve those schools. If the families who care most about education were also those who are most likely to avail themselves of school choice options, then the district schools would be left with the families who were generally less educated and less demanding. The remaining families would therefore be less likely to provide the critical feedback necessary to address problems and improve the school.

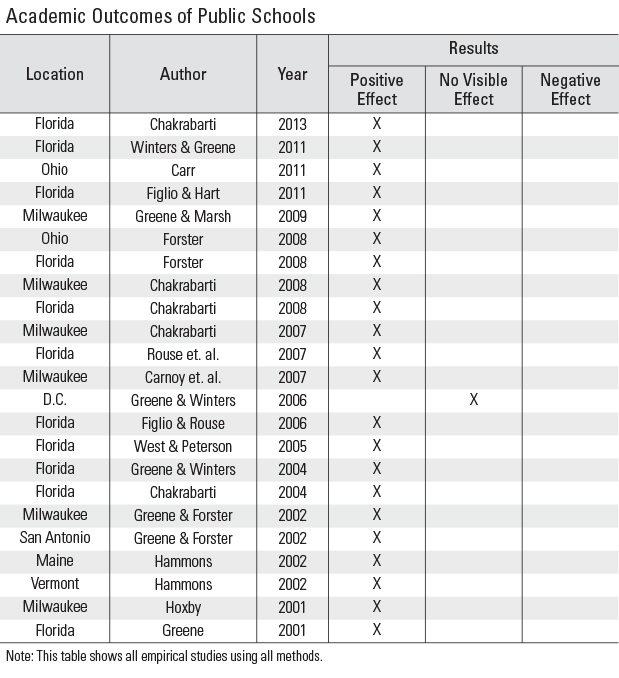

This is an empirically testable hypothesis. Fortunately there have been 23 empirical studiesinvestigating the impact of school choice laws on the students at district schools. Of those, 22 found that the performance of students at district schools improved after a school choice law was enacted. One study found no statistically significant difference and none found any harm.

District schools often operate as monopolies, particularly those serving low-income populations that have no other financially viable options. And sadly, a monopoly has little incentive to be responsive to the needs of its captive audience. Thankfully, the evidence suggests that when those families are empowered to “vote with their feet,” the district schools become more responsive to their needs, and student performance improves.

In other words, the exit option appears to enhance the voice of parents at their child’s assigned school. As Hirschman himself realized later in his life, “opening up of previously unavailable opportunities of choice or exit may generate feelings of empowerment in parents, who as a result may be more ready than before to participate in school affairs and to speak out.” Parental concerns carry more weight when the district school knows that those parents have the ability to send their children somewhere else—along with the money allocated for that child.

That leads us to the final question states and communities should address:

Question #3: Do resources alone determine a school’s effectiveness?

Schools obviously require resources to operate, but there’s no strong correlation between resources and results. If resources were what drove performance, then at about $30,000 per pupil, Washington, D.C.’s district schools would be among the best in the nation instead of the worst (though they have made significant gains since the advent of school choice laws in the city).

In 2012, education policy experts Eric Hanushek of Stanford University, Paul Peterson of Harvard University, and Ludger Woessmann of the University of Munich released a report on international and state trends in student achievement. They found that “Just about as many high-spending states showed relatively small gains as showed large ones…. And many states defied the theory [that spending drives performance] by showing gains even when they did not commit much in the way of additional resources.” They concluded:

“It is true that on average, an additional $1,000 in per-pupil spending is associated with an annual gain in achievement of one-tenth of 1 percent of a standard deviation. But that trivial amount is of no statistical or substantive significance.”

For that matter, it’s not clear that Arizona’s district schools will lose a penny as a result of the state’s choice laws. District schools would only lose money if they faced declining enrollment as a result of the choice laws—a sign that they had better change how they operate to better serve students and parents. But as education policy analyst Matthew Ladner observed recently, enrollment at Arizona’s district schools has significantly outpaced the growth in the number of students participating in choice programs in the last two decades.

From 1994 to 2012, district school enrollment increased by 176,989 students from 737,424 to 914,413. By contrast, the number of students participating in a private choice program went from 0 to only 30,587.

In other words, Arizona’s scholarship tax credit and ESA laws have barely slowed the growth in district school enrollment. Moreover, the U.S. Census Bureau projects that Arizona faces an impending surge in both the youth population and elderly population that will seriously strain the state’s education and health care infrastructure. Arizona policymakers will likely find that the lower-cost private school choice programs are necessary to reduce that strain.

Expanding Educational Choice For All

Roberts concludes by calling for a legislature “that doesn’t hate traditional public schools,” by which she means one that is focused on “giving all parents” the “choice of getting a decent education in the public schools—the ones that most Arizona students attend.”

Better yet? The choice of giving every child—not just “most” children—a decent education in whatever learning environments their parents deem best.