New Research on School Segregation Shows Startling Trends

Six decades after the landmark decision of Brown v. Board of Education, many students still attend schools that are segregated by race or class. And this isn’t just a problem because greater integration is, in and of itself, a worthwhile goal for society. It’s a problem because research shows that African-American students, especially males, concentrated in schools with large proportions of African-Americans tend to have worse outcomes than similar students in more integrated environments.

So what is the state of school segregation today? And how might school choice policies affect integration in schools? In my new study for the Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice—The Integration Anomaly: Comparing the Effects of K–12 Education Delivery Models on Segregation in Schools—I endeavored to answer those questions and more.

Is the US Public Education System Promoting Interracial Contact in American Society?

Given that a large majority of public school students attend schools that are determined by their neighborhood location, information about sorting across neighborhoods is warranted. The study notes the following trends:

- From the late 1960s to 1980, American neighborhoods became more racially integrated, as did public schools.

- After 1980, there was a puzzling divergence in those trends: Neighborhood racial segregation decreased, while segregation in public schools increased.

- Between 2000 and 2010, neighborhoods in almost all metropolitan areas experienced increases in interracial contact, but public school integration lagged behind.

- Between 1970 and 2009, American neighborhoods became much more segregated by income. That trend toward more income segregation across American neighborhoods has accelerated since 2001.

- The current public school system ties public schools’ attendance to residential location. As long as neighborhoods are segregated by race—regardless of the reason—public schools also will be segregated by race. This same reasoning applies to income segregation as well.

That said, more research needs to be done as to why the trends in neighborhood and public school segregation have diverged since 1980. While the end of court-ordered desegregation measures has caused a modest increase in segregation within public school districts, a large majority of racial segregation occurs across district lines.

Other possible reasons why public school segregation increased as neighborhoods became more integrated include gerrymandering of public school attendance zones by race or class and other decisions made by local public school boards.

How Does School Choice Promote Integration in Schools?

Some opponents of school choice believe that choice programs would allow parents to choose to segregate their children by race or income level. However, many aspects of American life—marriage, adoption, neighborhoods, etc.—have become more racially integrated in recent decades when individuals have had freedom to choose. The one glaring anomaly is public education, where families, except for the affluent, have not had the means to choose freely.

The cost of changing from one public school to another is typically quite high because school assignments are tied to housing. Greater school choice, however, lowers parents’ costs when changing schools for their children. That is, it allows parents to live in one public school attendance zone, but send their children to another school—public or private—located anywhere convenient to their residence or their place of employment.

With school choice, school integration is less directly tied to neighborhood integration, as parents can use school choice opportunities to access a wider variety of schools, not just the single public school for which their residence is zoned.

Universal school choice, in particular, would promote the increase of school integration by family income. Scholarships to higher- and middle-income families would give them more incentive to live closer to employment centers in what we now know as lower-income communities. Scholarship programs would allow new, high-quality school options to open in these areas. Universal school choice would also empower low-income families to send their children to schools located in neighborhoods only higher-income families may currently access.

The research on American school voucher programs indicates they promote integration in schools and tend to foster greater tolerance among students. Seven of the eight studies reviewed by the Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice found that giving parents vouchers to attend private schools led to increased racial integration in Milwaukee, Cleveland, and Washington, D.C.

The other study, which did not have ideal data, could not detect significant effects of the Milwaukee voucher program on segregation across Milwaukee schools. However, the Milwaukee voucher program had a very large impact on the distribution of students across sectors. In 1994, 75 percent of Milwaukee private school students were white, and in 2008 only 35 percent of Milwaukee private school students were white. Of this evidence, study author Greg Forster concluded, “This seismic shift was the result of the voucher program.”

Racial Segregation in Schools

| Author(s) | Year | Positive Effect | No Visible Effect | Negative Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Louisiana | Egalite and Mills | 2014 | X | ||

| Milwaukee | Greene, Mills, and Buck | 2010 | X | ||

| Milwaukee | Forster | 2006 | X | ||

| Cleveland | Forster | 2006 | X | ||

| D.C. | Greene and Winters | 2005 | X | ||

| Milwaukee | Fuller and Greiveldinger | 2002 | X | ||

| Milwaukee | Fuller and Mitchell | 2000 | X | ||

| Milwaukee | Fuller and Mitchell | 2000 | X | ||

| Cleveland | Greene | 1999 | X |

Note: This table shows all empirical studies using all methods.

Sources: Greg Forster, A Win-Win Solution: The Empirical Evidence on School Choice, 3rd ed. (Indianapolis: Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice, 2013), p. 21, http://www.edchoice.org/Research/Reports/A-Win-Win-Solution--The-Empirical-Evidence-on-School-Choice.aspx; Anna J. Egalite and Jonathan N. Mills, “The Louisiana Scholarship Program: Contrary to Justice Department Claims, Student Transfers Improve Racial Integration,” EducationNext 14, no. 1 (Winter 2014), pp. 66-69, http://educationnext.org/files/ednext_XIV_1_egalite.pdf.

The ideal analysis with regards to school segregation would also analyze segregation within schools. Research on North Carolina public schools found substantial segregation between classrooms—even within the same public school. Also, African American students were more likely to be assigned novice teachers relative to white students, and a significant amount of that disparity was due to the assignment of teachers within individual public schools. Two additional studies have compared within-school segregation between public and private schools. Both find private schools are more integrated within the school walls as compared to public schools.

Researchers have also studied the effect of school choice on students’ levels of tolerance. Five studies found students who were offered vouchers tended to express more tolerant views toward their “least favorite” groups—relative to public school students who were not offered vouchers in a randomized lottery. That is, these students who won the lottery and were offered a voucher tended to be more tolerant of the rights of those they considered undesirable. Two studies found no effect of voucher programs on political tolerance

While the evidence from the U.S. suggests a positive relationship between school choice and integration and tolerance, the evidence from overseas is mixed. The evidence from other countries indicates that school choice program design is essential. After reviewing those international programs’ effects on segregation in schools, I was able to suggest specific “Do’s and Don’ts” with respect to school choice policy design in The Integration Anomaly .

How Can School Choice Improve Educational Outcomes for African American Students?

Although the movement to prevent the government from forcibly segregating African American students away from “white” public schools was about personal liberty and integration for integration’s sake, it was also about improving outcomes for African American students.

School choice has been around long enough, now, that we have data showing that such programs can and do improve educational outcomes, especially for African American students.

The District of Columbia Opportunity Scholarship Program Increases Graduation Rates

The District of Columbia Opportunity Scholarship Program, created by Congress and signed into law by President George W. Bush in 2004, is a federally-funded school voucher program for low-income students living in our nation’s capital. Under the original law, students enrolled in public schools whose families earned 185 percent of the poverty level or less were eligible for scholarships of up to $7,500.

The voucher funds were created to offset tuition payments and other costs of attending a private school. Students assigned to lower-performing District public schools were given priority. The program used a lottery system to assign scholarships in the event that more families applied than scholarships were available. During the time period under study, $7,500 was less than half of what was spent per student in D.C. public schools.

Congress required that this program be subject to rigorous evaluation. Patrick Wolf of the Department of Education Reform at the University of Arkansas was the lead researcher on the evaluation, which was published in 2010. This random-assignment study followed students who applied for the scholarships: some who won the lottery and used their scholarships, some who won the lottery but did not use their scholarships, and others who applied but did not win the lottery.

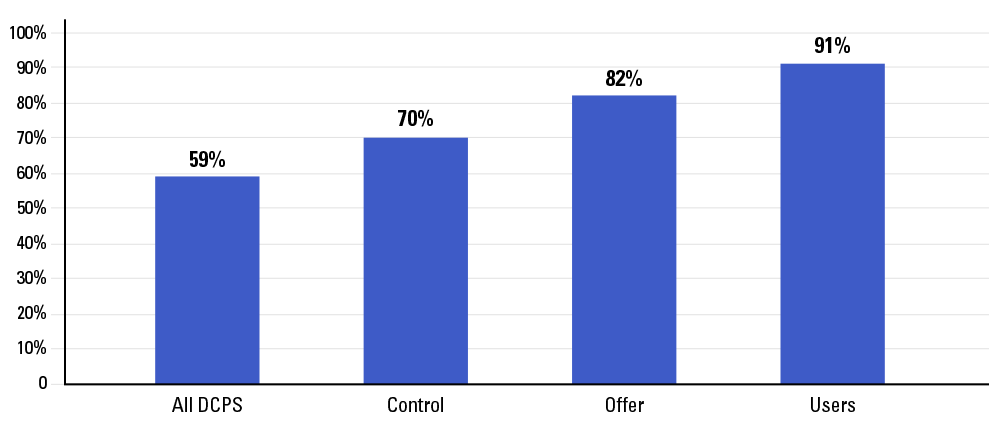

The study found students who applied for a school voucher but did not win the lottery later graduated from their public high schools at a rate of 70 percent. Of students who won the scholarship lottery but chose, for whatever reason, not to use the scholarship, 82 percent graduated from high school. Of those lottery winners who actually used the Opportunity Scholarship voucher to attend a private school, 91 percent graduated. For context, the graduation rate for all District of Columbia Public Schools students was 59 percent.

These improvements in high school graduation rates are enormous. For the 2013–14 school year, about 84 percent of D.C. scholarship recipients were African American, and 99.8 percent were nonwhite.

The New York School Choice Scholarship Fund Boosts College Enrollment

In the mid-1990s, some wealthy philanthropists created the New York School Choice Scholarship Fund. This scholarship fund provided $1,400 vouchers to as many as 1,000 low income-students per year. In an evaluation of this privately-financed endeavor, Matthew Chingos and Paul Petersen found “African Americans benefitted the most.” Based on their analysis, they also found “a voucher offer increased the college-enrollment rate of African American students by 7 percentage points, an increase of 20 percent.

If an African American student used the scholarship to attend private school for any amount of time, the estimated impact on college enrollment was 9 percentage points, a 24 percent increase over the college enrollment rate among comparable African American students assigned to the control group.” Put differently, these modestly-sized vouchers led to a college attendance rate of 45 percent for African American students who attended a private school, while African American students who were not offered vouchers had a 36 percent college attendance rate.

Greg Forster’s 2013 synthesis of the empirical evidence regarding school choice found that school voucher and other programs that allow parents to choose private schools are part of a “win-win” solution. That is, the evidence suggests that both students who exercise choice and students who remain in public schools benefit from school choice programs.

Forster noted that at the time of his report there had been twelve random assignment studies of school choice programs, including the evaluation of the D.C. Opportunity Scholarship program mentioned above. Like the D.C. Opportunity Scholarship study, these random assignment studies tracked outcomes for students who applied for school choice vouchers and were entered into a lottery; some of the students were denied a voucher, and others won a voucher via lottery.

Six of those studies found academic benefits for students exercising choice; one study found no discernable academic benefits from choice, and the remaining five of those studies found that benefits from choice were concentrated among only some students. Of these latter studies, the benefits of choice were typically concentrated among African American students and students who had previously attended relatively low-performing public schools before they were given a chance to attend schools their parents deemed better.

The vast majority of the evidence we now have shows that school choice can lead to more integration in schools—both public and private. In addition, the best studies show school choice programs create better educational outcomes for the most disadvantaged students. As I write in The Integration Anomaly, school choice may be the last, best hope for better integrating America’s schools. Perhaps giving parents more freedom to choose where their children attend school truly is the civil rights issue of the 21st century.