Parents and Teachers Both Want More Learning Pods

We knew parents liked learning pods. It turns out teachers might be even more excited.

When schools shut their doors in response to COVID-19, some parents worried their kids were not learning well through online instruction. Others feared a lack of social or emotional development. Among parents who transitioned to working from home, some felt they could not adequately help their kids through the school day and do their jobs simultaneously.

As a result, many families came together to form “pods.” There is some fluidity to their definition, but they all involve small groups of children, organized by parents, gathering to learn together. Parents either hire a private teacher or tutor to facilitate instruction in-person but outside of the school or classroom, often in a participating family’s home.

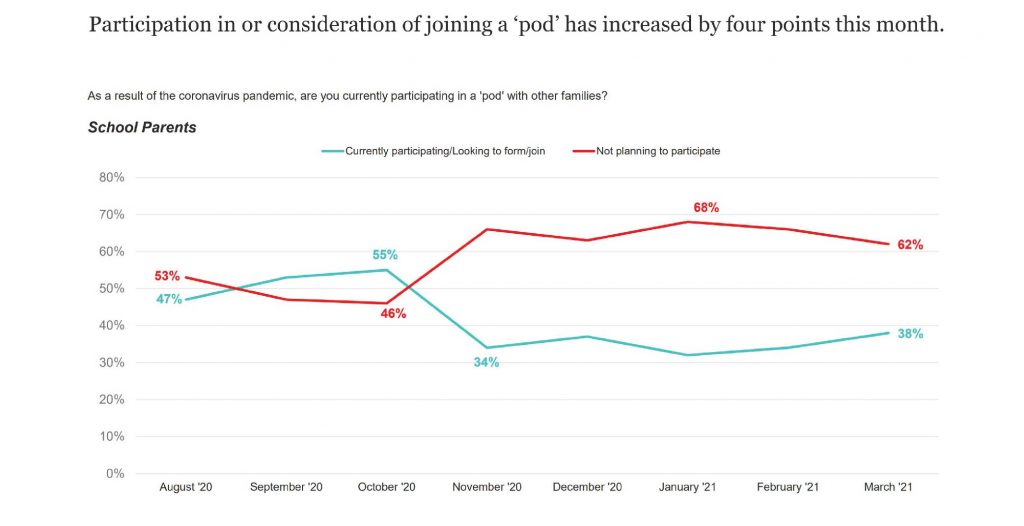

These pods were startlingly popular in early Fall 2020. According to our monthly survey of school parents conducted in partnership with Morning Consult, over half of parents indicated they were participating in or looking to join a pod. That level of popularity wouldn’t be sustained throughout the school year; still, out of every five families in March 2021, one was participating in a pod and another was looking to join one.

At least a third of parents have been interested in pods since November. The fact that pods have sustained that level of interest for the last five months hints that they might be here to stay. After all, since November, the country saw its largest spikes in COVID cases, the development and distribution of COVID vaccines, and the acceleration of school reopenings. If those massive events do not noticeably impact pod interest, it is fair to assume pods will stick around after this school year.

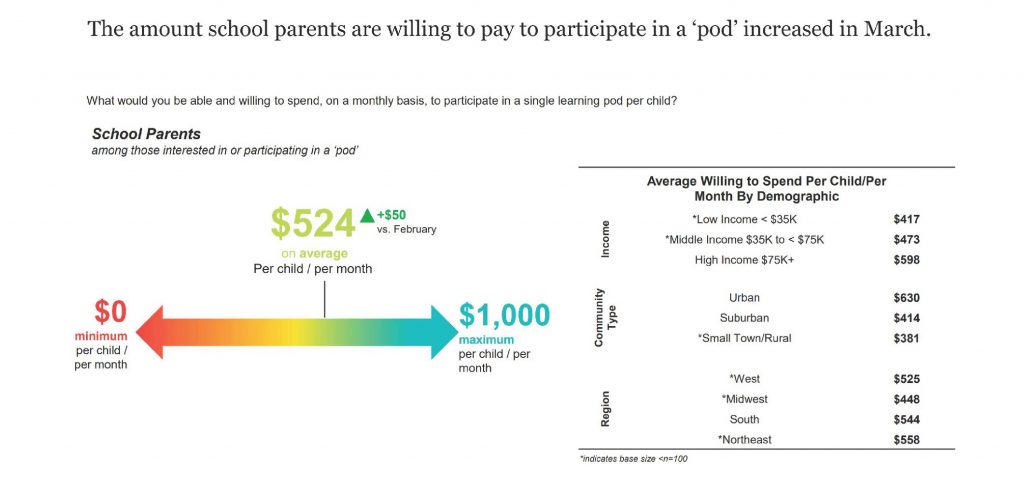

It’s one thing for survey respondents to say they’re interested in a particular schooling type, but we wanted to probe how serious that interest is. So, we asked how much parents would be willing to pay to be part of a pod. In March 2021, the average willingness to pay among those who said they’d be interested in participating was $524 per child per month. Notably, this average was $101 per child per month greater than our findings in January, which could signal that the intensity of interest in pods is rising even if the number of interested families has stabilized.

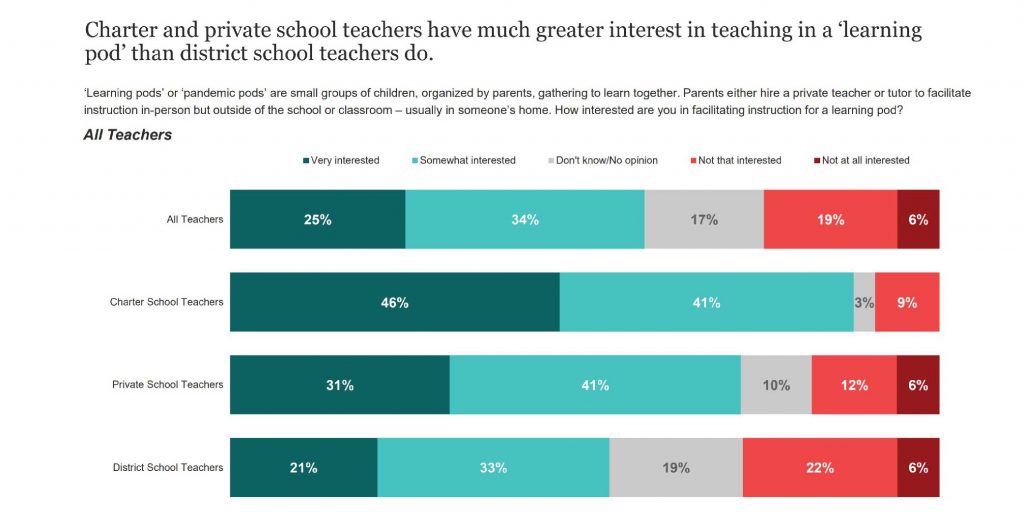

The learning pod model relies both on willing families as well as educators who want to step into a nontraditional model. We poll a representative sample of teachers every quarter, and in our most recent survey we asked them what they thought of this alternative structure. Arguably, they are even more enthusiastic than parents.

A strong majority of teachers expressed interest in teaching in a pod format, including 54 percent of district school teachers, 72 percent of private school teachers, and 87 percent of charter school teachers. One out of four teachers indicated they were “very interested” in teaching in pods, which might be a better indicator of how many teachers would seriously consider changing to this young sector if given an option. In short, there may be hundreds of thousands of teachers for whom teaching in a pod is an enticing option.

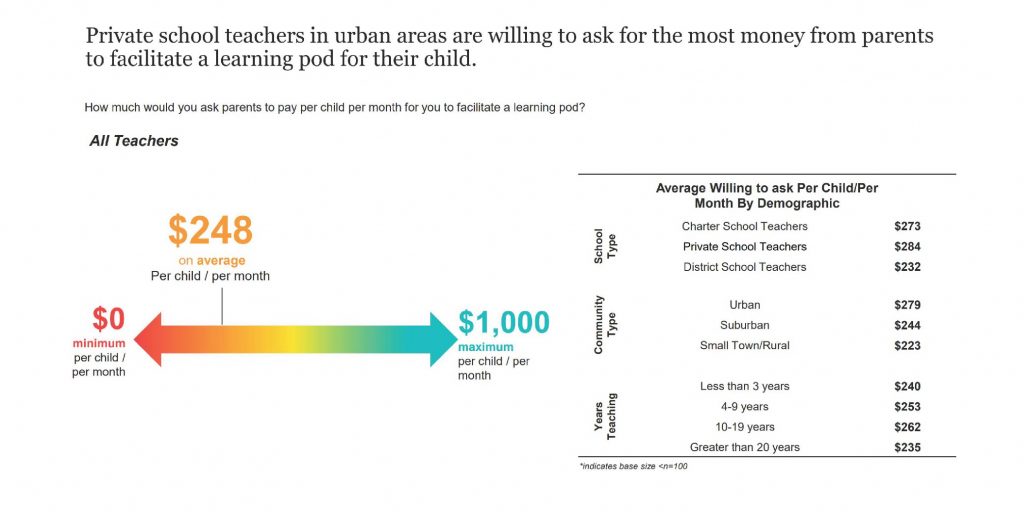

One reason teachers might not want to switch to pods could be financial uncertainty. So, we asked teachers that expressed interest in pods how much they would need to be paid to switch. Their average response was $248 per student per month. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the deeper into their career teachers are, the more compensation they demand, unless they have been teaching over 20 years. Private school teachers average the highest pay demands, and district school teachers average the lowest.

To put $248 per student per month into perspective, the average annual teacher salary in the United States was $57,282 in 2017, and the average elementary school class size was 21.6 according to the most recent data. Converting the salary to a monthly number and dividing that by the average class size, the average teacher currently makes about $220 per student per month.

Notice that the amount of money teachers would demand is less than half the amount parents are willing to pay—$248 per child per month compared to $524. Not only is there shared interest in pods between parents and teachers, but their respective financial needs appear to be complementary as well. One caveat: Parents and teachers could have had different expectations of how many kids would be served in a pod, which could throw their answers out of sync.

But the sizes of interest and the surplus of what parents are willing to pay gives us a pretty good idea that there is an under-tapped market for private teachers. Based on this data, we would expect more parents to form or find pods and more teachers to leave traditional sectors to facilitate them. Why haven’t pods grown more?

There is at least one private sector answer and at least one public policy answer. For the former, pods have far less recruitment reach than a brick-and-mortar school, so finding a good teacher could be difficult. A service that lets teachers build share interest and qualifications for parents to browse would provide tremendous value—perhaps like an Angie’s List for pods. If at least one service grows enough to develop network effects, parents and teachers could connect in a marketplace like never before.

Choice-friendly education finance policy can help, too. Right now, pods are less likely to be an option for families with lower household incomes. If public K-12 education funding followed students, the opportunity to join or form pods would expand to many more families. Establishing education savings accounts (ESAs) is a great option. ESAs allow families to take government funding already dedicated to their children’s schooling and use that money to mix and match educational resources to their children’s needs. Parents could spend as much as they needed on the pod, additional tutoring, books, certain extracurricular activities, or even save leftover funds to help pay for college.

Our survey data clearly indicate there is both demand and supply of private learning pod teachers. The market is there; it just needs a spark. With some entrepreneurial ingenuity to handle some administrative burden, along with a liberation of K-12 education funding, more kids could receive an education that’s better tailored for their success.