What We Can Do About School Choice’s Supply-Side Problem

If you build it, they will come.

A memorable line, a memorable scene.

But what happens if you know they’ll come, and you just can’t get it built in a timely fashion?

In one of our recent reports, The Private School Landscape, we tested the theory that educational choice programs that increase access to private schools will, in turn, increase both the number of students in those schools and the number of seats available overall.

Our theory was wrong.

Or at least it hasn’t taken hold yet in the way Milton Friedman predicted it would back in 1955 when he first laid out the merits of school choice.

Why haven’t we seen noticeable growth in private school populations and capacity? There are a number of possibilities, including limitations on the number and type of students participating; less funding for private school choice students than public school students; and unreliable funding from year to year.

Let’s also remember that public schools have a built-in population pipeline that’s projected to grow by 3 percent by 2025. In places where choice is limited by income, access or the number of private schools, the public school becomes the default option for most families.

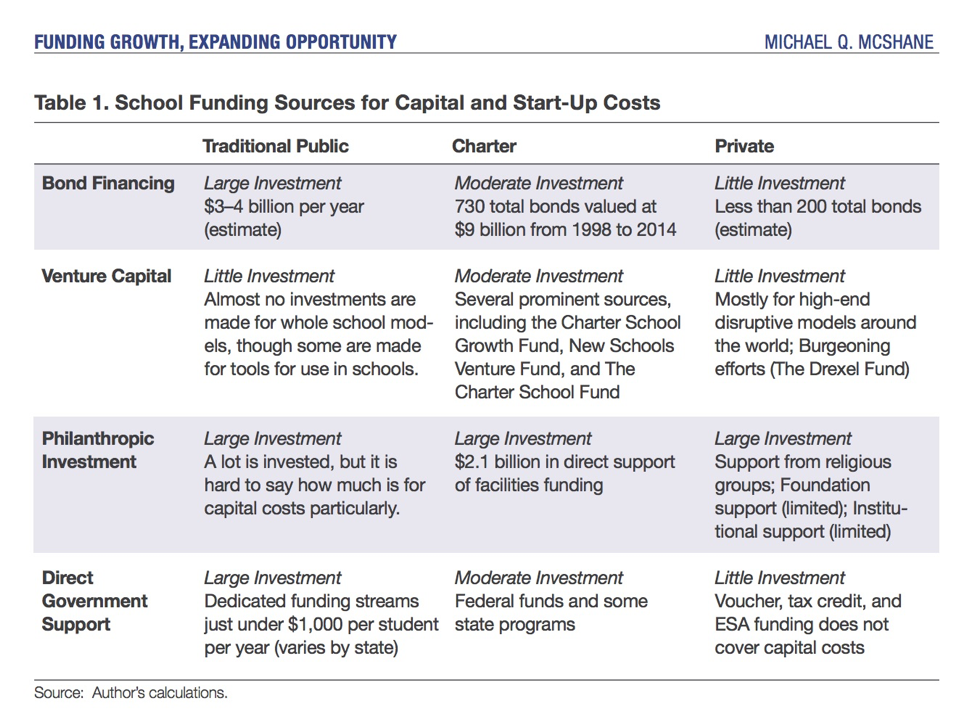

Another reason for slow growth may be the inability for private schools to expand quickly because they lack access to the low- or no-interest capital that’s available to traditional public and charter schools for infrastructure needs.

As Director of Education Policy at the Show-Me Institute and former American Enterprise Institute Scholar Dr. Mike McShane noted in his 2015 report, Funding Growth, Expanding Opportunity, “Because private schools in the vast majority of instances will never be able to access public dollars, venture finance is not in a great position to solve some ongoing needs. Private schools have generally looked to more traditional avenues of philanthropic support when they have needed a new building or wanted to start fresh.”

In other words, school choice programs have begun to level the playing field for students, but private schools are still behind the curve when it comes to the way they have to build new schools or expand existing facilities to educate additional students. Meanwhile, their counterparts in the public and charter sectors have access to municipal bonds, low-interest loans and venture capital.

You might ask why we would want to grow the supply of private school seats in America when it seems like there already are so many options available. Three reasons:

- There’s a tremendous imbalance between the percentage of people who would prefer a private school education and the number of students who actually are accessing a private school education.

- Once families have access to a private school, they are overwhelmingly satisfied with their choice and their experience there.

- There’s an enormous and ever-growing body of evidence showing that private school educational choice programs improve academic outcomes for students and schools, save taxpayers money, reduce segregation and improves students’ civic values.

If you prefer to focus instead on the economic arguments behind educational choice, a fourth and highly compelling reason—the driving force behind Dr. Friedman’s school choice vision—is that a diversity of school types within a competitive environment will help all families find the best option for their students.

But as our study showed, the private school landscape has a supply-side problem.

As we noted above, capital funding is just one possible component of that slow growth; private schools have many other reasons—inconsistent per-pupil funding, burdensome regulations, mandatory testing—not to take part in educational choice programs.

Still, it’s clear the playing field is not level when a public school district can ask the voters to remedy a longstanding deficit via public referendum despite decades of declining student enrollment, but a private school must spend years raising money—even if there’s an immediate demand for more seats.

An interesting side note: There are those who oppose educational choice on the grounds that many of the private schools that receive vouchers or tax-credit scholarships are religiously affiliated. A recent study out of Milwaukee found that vouchers have, indeed, been a strong source of revenue for Catholic schools in that city, though the funding has had limited effect on the churches with which those schools are affiliated.

Knowing that demand for non-public education is high, perhaps those who wish to see more secular private schools would support making it easier for them to start up or expand by increasing access to low-cost loans instead of forcing them to engage in years-long capital campaigns before they can even break ground.

Of course, there’s an argument to be made that all types of schools should consider new solutions to their real estate needs, pushing beyond the typical bricks-and-mortar ownership model. Online schooling requires very little square footage, and charter schools have long been pushing the envelope when it comes to facility reuse, leasing space or putting schools in non-traditional settings.

In other words, we may not have to build it for them to come, but overall, we need to pay closer attention to what families want versus what’s currently available to them.

If we know that parents would overwhelmingly choose private schools if they could, it follows logically that we should make it easier, not harder, for those schools to start up or expand to meet that demand. That includes avoiding burdensome regulations and providing a steady stream of funding for educational choice programs. It should also include making sure those schools have access to capital that would help them serve more students.