Defining Market Failure (with Examples)

Introductory courses in economics usually focus on perfect competition and why markets are more efficient than other institutional arrangements, such as monopolies or oligopolies. Under certain conditions, markets will generate the best outcomes for consumers and society. In the words of economists, markets achieve equilibrium when the quantity consumers demand of a good or service equals the amount of a good or service supplied.

But markets aren’t always perfect, and certain conditions may prevent market equilibrium. Market failure is an economic term applied to a situation where consumer demand does not equal the amount of a good or service supplied, and is, therefore, inefficient. Under some conditions, government intervention may be indicated in order to improve social welfare.

The main types of market failure include asymmetric information, concentrated market power, public goods and externalities.

Though there are other types of market failure, in this piece I discuss the four most common types of market failure with examples from various industries. Then I discuss market failure in K–12 education as an example.

Information Asymmetry

Efficient markets require high levels of transparency and free flow of information. When one party in a transaction has better information than the other party involved, then there’s opportunity for exploitation. A classic economic example is the “Lemon problem.” In the market for used automobiles, information asymmetry occurs when sellers know more about what they are selling than consumers do. The consequence is that buyers may unknowingly purchase cars with defects (lemons) at a higher price than they would have been willing to pay if they had information about the defects. Today, warranties and online information services, such as Carfax for the auto market, help address these problems and mitigate the “Lemon problem” for consumers.

Concentrated Market Power

In markets with high levels of competition, companies and organizations have an incentive to produce goods and services that consumers value, at low cost. If they do not meet consumer demand or fail to keep prices low, then the company or organization will lose money or go out of business because consumers can easily find substitutes elsewhere. Agricultural crops, such as corn or soybeans provide an example of highly competitive markets. Many farmers produce similar crops. Farmers who produce bad-tasting corn or who price their corn too high will likely lose customers because those customers can easily find other corn that’s better or cheaper elsewhere.

In contrast, a monopolist is the only producer of a good or service, and market power is concentrated in the hands of a single producer. There are no other producers, no other appealing substitutes and the single organization has so much power, no other competitor can gain footing in the market without help from some other intervention (economists refer to this as “barriers to entry”). As a result, consumers are in a weak position to influence the monopolist’s behavior because they have nowhere else to get that good or service. The monopolist has weak incentives to cater to consumers’ demands. Under a monopoly, the company or organization will produce too little or poor quality goods or services while pricing them above marginal cost. Markets like this will operate inefficiently, too.

The case of Martin Shkreli is a good example of monopolistic behavior in the real world. Forbes described Shkreli’s business model like this:

“There’s a number of pharmaceuticals out there that are well out of patent but still have small and useful markets. FDA regulations (no, we’ll not go into the details of how or why this happens) mean that it’s not as easy as one might think to produce generic versions of these out of patent drugs. So, as a business plan, buy up the rights to the permit-ed (as in, with a permit, not just those allowed, as in permitted) generics and as a result of the difficulty someone else will have in getting into the same market, some pricing power is available. You can then raise the price and start to bank your considerable profits.”

Shkreli raised the price of Daraprim, a kidney drug that has been around for decades, by 5,000 percent, from $13.50 to $750, sparking widespread outrage. But instead of government intervening in this case, another pharmaceutical company created a close substitute that provides patients relying on Daraprim with a potential alternative. The case for government intervention in the face of market failure may be more nuanced than what some may perceive. Forbes also reported:

“If a monopoly is contestable we need do nothing about it. It’s not enough, further, for us to observe that someone appears to have a monopoly or near monopoly on something. Because it’s entirely possible (this forms the basis of one strand of Paul Krugman’s Nobel-winning work) that the efficient scale of a producer can be the dominant global producer. What we need to prove, before we try to regulate, is that not only is there exploitation of that market power, there’s no possibility of contesting it.”

Many also point to public K-12 schools an example of a monopoly, discussed more below. Milton Friedman often pointed this out.

When a market with many buyers has limited competition and market power is concentrated in the hands of only a few producers, you have an oligopoly. In nearly every real-life instance of oligopoly, the providers may ultimately collude with one another, agreeing not to compete and raising prices collectively to increase profits at the expense of buyers who have no other choice. An example of oligopoly from recent history is the oil and gas industry. Governments, in turn, have responded to oligopolies by creating laws against price fixing and collusion.

Public Goods

A public good has two features: It is nonrival and nonexcludable. What does that mean?

Nonrival means that consumption of a good or service by one party does not prohibit consumption of the same good or service by another party. The broadcast of a TV series is an example of a nonrival good. If I watch an episode of The Office, you could also watch that same episode of The Office. A rival good means that consumption of a good or service by one party prevents its consumption by another party. An apple is one example. If I ate an apple, you could not eat that same apple.

A nonexcludable good is one where nonpaying consumers cannot be prevented from accessing the good. A classic example is national defense. Taxpayers fund national defense, but it is impossible to prevent individuals who do not pay taxes from accessing it. A mural is another example of a nonexcludable good, where anybody who happens to look at it may enjoy it. A good is excludable if it is possible to prevent nonpaying consumers from accessing it. Some examples of excludable goods would be HBO, a premium Spotify subscription, a Starbucks frappuccino or anything you might buy at a retail store.

The delivery of public goods by private companies or organizations can lead to the “free-rider” problem. The free-rider problem can happen when enough people can enjoy a good or service without paying for the cost to supply it that there’s a danger that, in a free market, the good will end up under-provided or not provided at all by a private company. The assumption is that private companies and organizations won’t supply something if they know they will lose money on it. In that case, many economists believe there is a role for government, rather than private companies, to provide or subsidize those goods or services using taxpayer dollars.

Let’s take police protection as a service. If only 25 percent of the citizens in a district pay a private company to provide them police protection, by nature of the work, all of the citizens in that area would benefit from the safety that company was able to provide the paying customers’ neighborhood. So the private company would theoretically be giving away free protection to the nonpaying 75 percent of citizens. Because that isn’t in the best interest of the private company’s bottom line, it would theoretically find ways to limit its services or abandon the venture. It makes sense in this case for government to use taxpayer dollars to provide police protection to all citizens.

Externalities

Externalities, sometimes called “spillovers” or “neighborhood effects,” occur when a transaction generates a benefit (positive externality) or cost (negative externality) on a party not directly involved in the transaction.

A classic example of a negative externality is pollution that results from the production of a good in a factory. Individuals living around the factory are exposed to the pollution and may cause them health issues. An example of a positive externality may include workplace CPR or First Aid training. This could save lives outside of the workplace without requiring potential beneficiaries to pay for the training.

Externalities pose problems for markets because the price of a good or service associated with an externality do not reflect the total societal benefits or costs from those goods or services. As a result, companies or organizations will produce too many or too few goods or services, depending on the externality. There may be a role for government to subsidize goods or services that generate positive externalities—often via tax breaks—because of the positive effect a company or organization is having on a community, whether inadvertently or intentionally. There might also be a role for government to tax or fine negative externalities to influence companies to reduce that harmful spillover. The basic idea is that the government can help influence a market to make more choices that will help society and fewer that will hurt society.

Tying It All Together

To tie it all together, market failure can occur under certain circumstances, including when:

-sellers in the market have access to important information that would affect a buyer’s decision-making that buyers do not

-the market lacks competition because one or few providers have a disproportionate amount of power within that market

-an individual’s consumption of the goods and services provided in the market doesn’t affect another’s ability to access that good or service and taxpayers and non-taxpayers alike ultimately benefit from the good or service being provided

-costs and benefits are unbalanced for providers in the market (In other words, providers in the market are producing too little of their goods and services because they aren’t bringing in the right amount of money to compensate for the value they are providing OR they are producing too much of their goods and services because some negative externality goes unchecked and ultimately makes it easier for them to produce that good or service.)

An Example: Market Failure in American K–12 Education

When discussing the role of government in K–12 education, it is crucial to make a distinction between education and schooling.

Nobel prize-winning economist Milton Friedman once said, “Not all schooling is education nor all education, schooling.” It’s possible for someone to receive a lot of schooling without learning much. There are many ways to deliver education and build human capital. Students can learn, yes, by attending brick-and-mortar schools, but education also happens online, in trade schools, when working with special needs therapists, at museums, in a theater. The list goes on, but the point is traditional schooling as we know it today is evolving because the needs and demands of parents and their children are evolving.

What does America’s K–12 public education market look like today?

Broadly speaking, education meets the narrow definition of a public good. It is nonexcludable and nonrival.

The student receiving an education experiences most of its benefits. For example, more education increases the likelihood of getting the dream job, earning a higher income and of being civically active.

As a public good with positive externalities, others also benefit from the student’s education. For instance, a higher income means more taxes to fund public programs, and a more active citizen means more voting and volunteering. We all generally agree a society where more citizens participate in democracy is a better society.

As such, economic theory predicts that private markets alone will produce a suboptimal level of education.

Public schooling, on the other hand, is one of several mechanisms or settings for delivering education. It does not meet the definition of a public good. It is excludable because classroom space is limited and because school district lines keep some students in and others out.

Unless families can afford tuition for a private school, to home school or to move to a different district, they have few or no alternatives to their residentially assigned district school.

Those who claim that public schooling is a public good with positive externalities are actually conflating public schooling with public education. In reality, private schools, home schools and other learning providers, such as special needs therapists and tutors, also deliver education that benefits the public.

So should K–12 schooling be left alone to be a completely free market, or are there market failures government can help address?

Because America does not have a system of public education but rather a system of public schooling, its education market clearly has some market failures to address. A lack of competition and information asymmetry most egregiously affect the experiences of too many students, the consumers.

America’s system has been built such that only wealthy families may access alternative education providers to their ZIP Code-assigned public school. They can pay for private school or moving to a different neighborhood with public schools that fit their needs better. Socioeconomically disadvantaged families don’t have those options, more often than not.

Because of that, public schools not only have a monopoly on public funding for the education they provide, but they also have a captive audience of consumers who lack the power to choose alternatives.

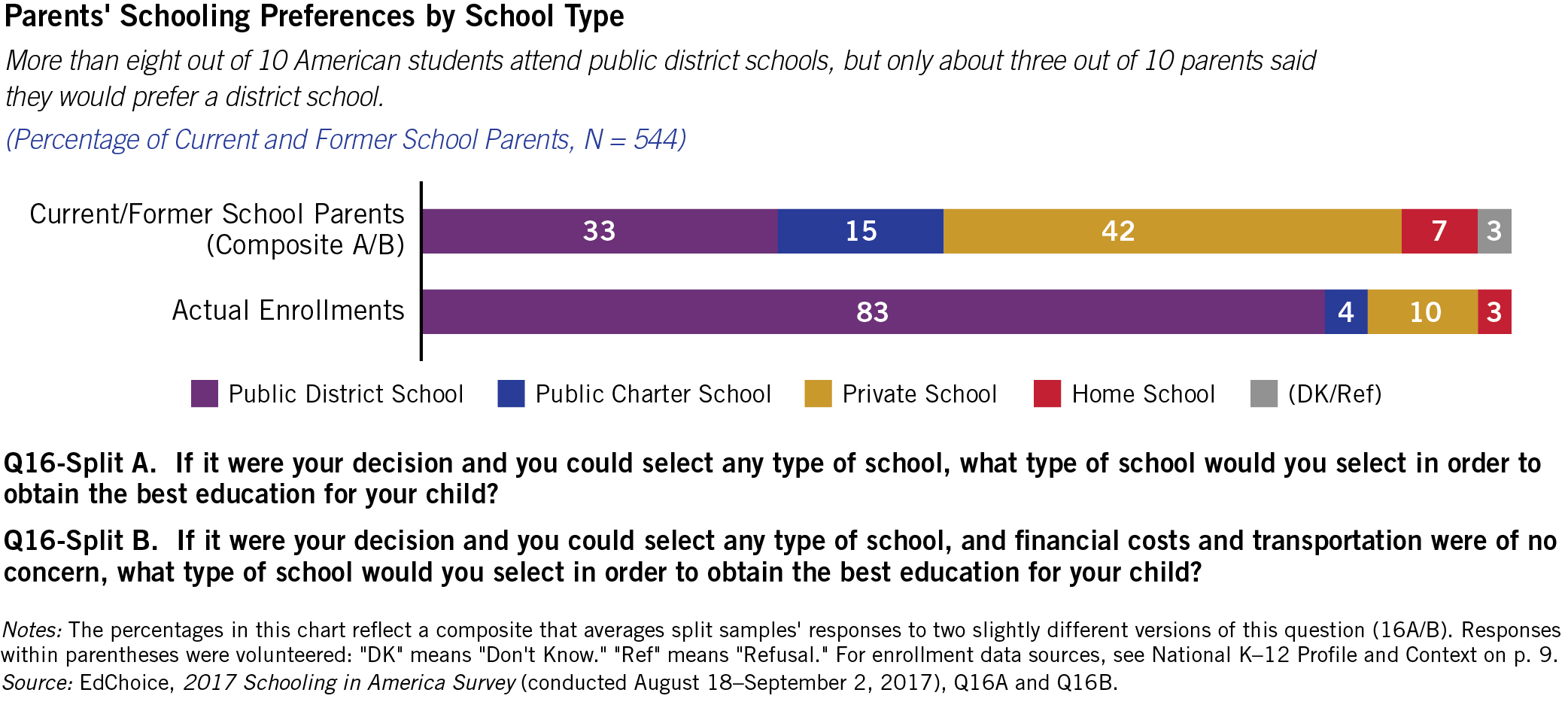

And there is evidence to support that this market failure—concentrated market power—isn’t just a theoretical presence in our education system. Today, more than 80 percent of America’s students attend public district schools, yet a recent national survey shows education consumers would actually prefer to choose within a more competitive education market.

Moreover, imperfect information, or information asymmetry as we defined it above, is another factor that produces sub-optimal outcomes if education is left solely to private enterprise. As Joshua Goodman, an economist at Harvard University, noted:

“Here’s what I think the biggest problem in thinking of schools as a classical market. Econ 101 models assume consumers observe product quality. But schools are complicated goods, and quality, particularly a school’s long-run quality, is hard to judge for many parents. It takes a lot of time to figure out whether this school and these teachers are serving my child well. Unlike restaurants or supermarkets, where quality can be judged at the moment of the purchase, school quality reveals itself later.”

What should the government do to intervene in K–12 schooling market failures and what shouldn’t it do?

In treating schooling, rather than education, as a public good, government has transformed public schooling into a monopoly over many decades.

Corey DeAngelis, policy analyst at the Cato Institute, argued:

“Since schooling fails both parts of the public good definition, the free rider problem does not exist, and we do not need the government to operate schools. If government is not necessary for the operation of schools, we should not promote policies towards that end.”

This idea isn’t new.

Milton Friedman, who popularized the idea of school vouchers in the 1950s, argued that government has a role to fund education, but it can do so without being the sole provider. If there’s a role for government today, he said it should be to treat public schooling as it would any other monopoly.

Because education, broadly speaking, meets the definition of a public good and schooling does not, government can provide parents opportunities in the way of publicly funded programs that allow them to access all of the educational providers in the schooling market rather than allocating all of the available public funds to itself so it may operate schools, a systemic shift that Friedman originated and many other economists support.

States are increasingly offering a relatively new way of funding education that empowers parents: education savings accounts (ESAs). With ESAs, parents can access tutoring, pay for tuition or enrollment fees, access online courses and purchase other education-related goods and services. These innovative educational funding mechanisms mean that public education can be unbundled, so families can access a more customized learning experience for their children.

Information asymmetry persists in the K–12 schooling market, but recent work by Michael Lovenheim of Cornell University and Patrick Walsh of St. Michael’s College suggests school choice may be part of the solution to this problem.

They studied how parents collect information on school quality, and their results suggest that the information parents have about local schools comes from the environment they face, “and that parental information depends not just on the availability of data but also the incentive to seek and use it.” In other words, parents with few educational options beyond their ZIP Code-assigned public school face weaker incentives to seek information about their children’s schools than parents who have more educational options.

The government can take steps to incentivize education department administrators, schools and other providers to publicize information so families can make informed, holistic decisions about their educational choices.

Though not a panacea, government can play an integral role in preventing education market failures by increasing families’ access to educational options.

As states continue to change their education systems, we at EdChoice will continue to analyze these developments and communicate the evolving state of K–12 education in America to our audience. To learn more about school choice programs in the states, visit our School Choice in America Dashboard.

References and Other Market Failure Resources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Free-rider_problem

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Market_failure

http://econlog.econlib.org/archives/2008/08/public_goods_ex.html

https://www.edchoice.org/school-choice/types-of-school-choice/education-savings-account/

http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/bios/Pareto.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Market_for_Lemons

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barriers_to_entry

https://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/10/18/the-gap-between-schooling-and-education/