2020 Schooling in America Series: COVID-19 Impacts on K–12 Education and Racial Disparities

K–12 education and the households in which students are raised, like the rest of the world, experienced major upheaval in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. But how did parent stakeholders within the education system feel during the pandemic-induced switch to distance learning during the spring?

As part of our 2020 Schooling in America survey, which we’ve conducted annually for the past seven years, EdChoice asked 1,605 adults, including parents, in late May and early June about the impact COVID-19 had on the education system.

By that time, coronavirus-related deaths in the United States had eclipsed the six-digit mark; schools nationwide were wrapping up spring semesters in which teachers and students had to pivot to distance learning around their midpoints; 44 private schools confirmed they would not reopen their doors due to the economic downturn; and state legislatures were grappling with how to fund, assess and safely reopen their K–12 education systems in time for the fall.

Despite these realities, a majority of the public gave good grades to local institutions, including schools (66 percent grading an “A” or “B”), on pandemic responses—which were much higher than those of national institutions like the federal government. Education Next, in a different survey of families, found a majority of parents (72%) were somewhat or very satisfied with schools’ responses.

Diving deeper into schools’ responses, parents emerged from the pandemic-intrusive spring semester feeling more inclined and prepared to facilitate virtual learning: two out of five (40%) parents were “extremely/very prepared” to facilitate their children’s distance education, with a similar proportion saying they would be likely to choose distance learning in the fall should their school district provide it as an option.

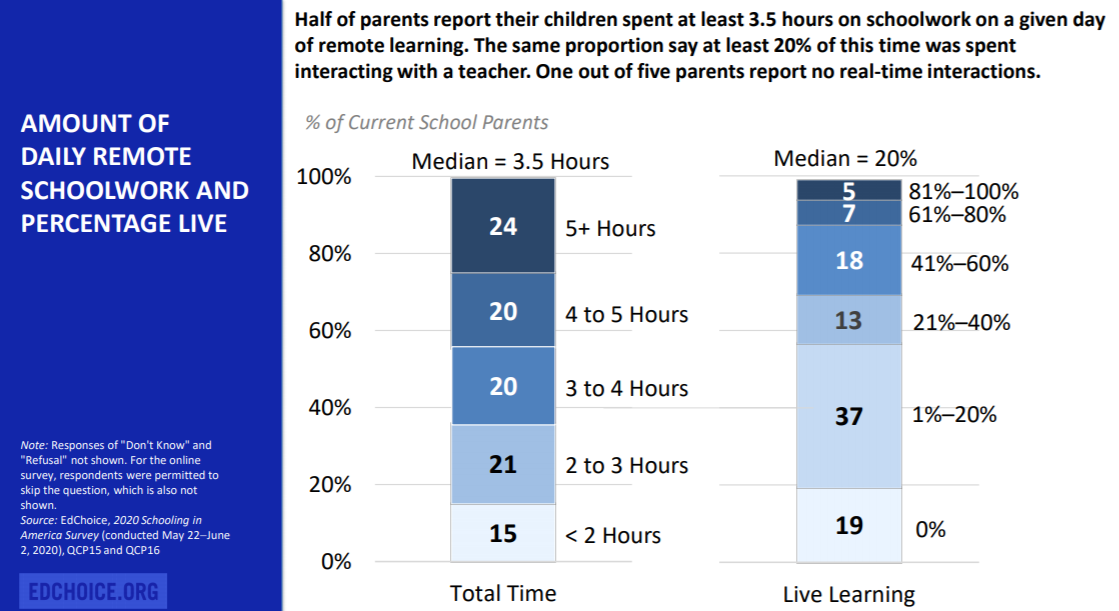

Facilitating e-learning is a lot of work, though, and parents experienced distance education differently depending on factors like home environments and school resources. The median time parents reported their children spending on coursework following the switch to virtual learning was 3.5 hours, with a surprising one out of five parents reporting no real-time interactions with a teacher following the switch.

Gauging students’ learning achievement was outside the scope of these parent-focused questions, but YouthTruth’s survey of middle- and high school students saw a large drop of those reporting they “learned a lot” during the e-learning switch (60% before, 39% after). Other polls, like AEI’s May Coronavirus Family Impact Survey, also found parents giving schools fairly positive marks on the switch to virtual learning, with half reporting receiving emailed assignments from teachers and about a third (31%) of students receiving school-issued laptops to take home for coursework.

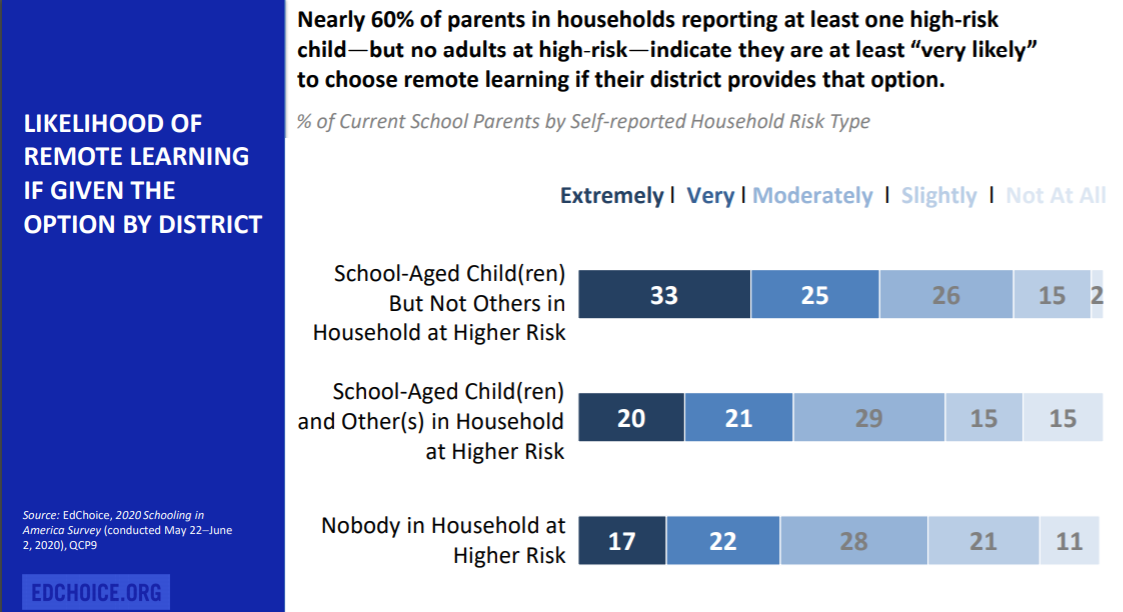

Of course, a big reason parents likely expressed preferences for virtual learning in the fall is due to safety concerns stemming from COVID-19. Nearly one-fourth (22%) of parents have at least one child who is, according to CDC guidance, at a higher risk for severe illness from the virus. About a third (31%) of parents were extremely concerned about their children contracting the virus should in-person classes resume in the fall.

Fifty-eight percent of parents in households with at least one child who is high risk said they would be extremely or very likely to choose a remote learning option compared to 39 percent of parents in households with no one at high risk.

But just because parents expressed safety concerns and were favorable to virtual options, it doesn’t necessarily follow that they don’t want the “normal school experience” for their children. Close to half (47%) of parents in the EdChoice sample were extremely or very concerned about schools not being able to open fully or on time in the fall.

Whether these concerns will come to fruition may largely hinge on safety measures schools and leaders take to ready classrooms. AP-NORC, for instance, found a vast majority of Americans saying measures like daily disinfecting (81%), mandatory facemasks for staff and students (69%), and daily temperate checks (66%) were “essential” for schools to safely reopen.

To varying degrees, parents observed changes in their children’s happiness and stress levels during the switch to e-learning. They said their children were more stressed (45%) during the pandemic than before it (34%) but that levels of unhappiness haven’t changed significantly (38% vs. 40%). It remains to be seen how, if it all, additional upheaval in the education sphere may affect these indicators in the fall.

When breaking out these results among racial and ethnic lines, we found some interesting results among subgroups. Hispanic parents were more likely to report the pandemic leaving their students unhappy (46%) and stressed (52%) than white parents, and a third of parents indicated they were “not at all” comfortable with their children returning to schools this fall; however, Black parents were also more likely to report their children’s social and emotional well-being was in a better place than before the school closures in the spring.

Black parents (26%) were also more likely than white (20%) and Hispanic (20%) families to say they were “extremely likely to choose remote learning in the fall This may make sense when considering Education Next found Black and Hispanic parents were more satisfied than white parents with their e-learning experiences.

We hope you’ll take a look at the complete results from this first wave of Schooling in America survey data. We’ll have additional results available in the coming weeks about school choice policies, K-12 schooling preferences and the education landscape in America, as well as data about views on homeschooling.