How Do “Bad Parents” Affect Schools?

Charges of “cream-skimming” is a favorite tactic used by some to scare away support for school choice. Skeptics say that should portable student-based funding be implemented, the most-engaged families will rise to the top (the “cream”) and private schools will separate them from the rest. Thus, public schools will be left to serve only the more educationally lethargic families—whom public school advocates call “bad parents.”

School choice supporters and researchers have questioned the validity of such claims, noting that chartered public schools, open to all, must admit students randomly while most private school choice programs are designed solely for disadvantaged families—as are many private schools. Thus, claims of cream-skimming might be more demagogic than accurate.

But let’s say cream-skimming did happen in the way critics of school choice imagine it does. Could that practice actually help not only those “skimmed” but those “left behind” as well?

If such market forces influenced the government-run system—which school choice would allow—funds would flow to where they are needed most: not supporting bureaucratic bloat but rather rewarding and properly equipping teachers.

In America’s current private school choice climate—again, in which only economically disadvantaged students are largely eligible—23 out of 24 empirical studies have found the health of public schools improves amid competitive pressure from private schools. One study found no effect; notably, the program analyzed was intentionally shielded from competition’s healthy incentives. Point being: When students leave—whether they are the cream of the crop or not—their affected public school gets better.

And why might that be?

Ignoring their backgrounds or abilities, students whose parents opt not to use school choice programs were going to be in public school anyway regardless of whether or not the school choice program exists. Now, however, those very students of presumably “bad parents” have more resources devoted to their education because the students who left took only a portion of their funding. Moreover, their teachers aren’t distracted by students who clearly didn’t want to be there in the first place.

Will impacted public schools have to make adjustments because of declining enrollments? Absolutely. But normal (private) institutions are always looking for ways to be leaner so they may offer people better prices and services. If such market forces influenced the government-run system—which school choice would allow—funds would flow to where they are needed most: not supporting bureaucratic bloat but rather rewarding and properly equipping teachers.

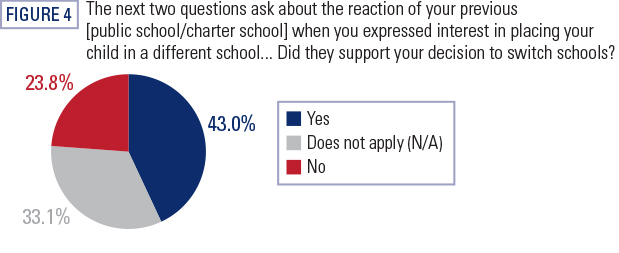

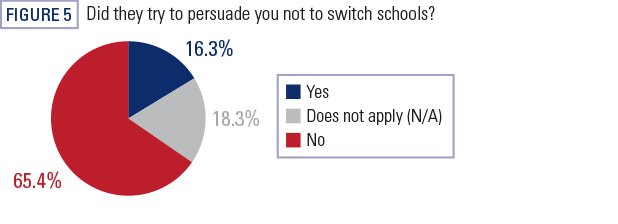

Such effects or desired outcomes may be why, in the nation’s largest school voucher program, a plurality of surveyed Indiana parents using vouchers or tax-credit scholarships said their public schools supported their decision to leave. Moreover, 65 percent of those parents said their previous public schools did not try to persuade them from leaving. If their departures were so harmful for the other children with “bad parents,” wouldn’t more public educators try to stop those parents from leaving?

Call those parents the “cream,” call them whatever you want, school choice provides the opportunity to empower those who crave empowerment. But more important, that very action also means school choice will allow public schools to focus what is now scarce time, attention, and resources on the children who need more of it. Perhaps then, those children of “bad parents” will have a fighting chance to climb to the top, too.