Breaking Down “The Achievement Checkup”

More than 40 years ago, Stevie Wonder sang a plea for impoverished city kids in his hit “Living for the City,” in which he called for the larger community to work for a better day for those kids.

The plight of America’s low-income, urban children has been well-documented, through films, such asWaiting for Superman and popular books like Jonathan Kozol’s Savage Inequalities and Alex Kotlowitz’ There Are No Children Here. As a society, we are continually sent messages about a hopelessness experienced when growing up poor in an American city.

Now that our new century is 15 years old, it’s time we ask: Are our kids in poverty still only “living just enough for the city?”

For certain, children in poverty are facing tough situations, made even tougher by steep drops in employment and wages that accompanied the early 21st Century recession and slow economic recovery. In Baltimore, for example, 29 percent of children are living in families with income below the poverty line, compared to 11 percent statewide. That is a dramatic statistic, given that Maryland was identified as the wealthiest state in the country in 2013 and 2014.

City school systems face huge challenges today partly because of the many needs of the low-income families they must serve. Most have very low high school graduation rates compared with school systems outside of the cities—as much as a 50 percent difference. And many of the children who do graduate rarely attend or succeed in college after graduation. Philadelphia, for instance, has only a 10 percent college graduation rate among its public school students, 40 percent of whom live in poverty, and 80 percent of whom are eligible for free school lunch.

An image has developed in our society of poor kids with parents who have been rendered helpless by their lack of education and lack of access to resources. But, is it true that low-income parents are uneducated, have “given up,” or are altogether unaware of how to change their circumstances? Or are there places where those families have found a way to live more than “just enough” for the city?

In the Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice’s latest research, The Achievement Checkup, I examined the long-term academic outcomes of one of the programs attempting to help low-income families beat the odds—The Children’s Scholarship Fund Baltimore (CSFB), an organization that provides need-based K-8 scholarships to low-income families.

The privately-endowed scholarship fund is open to all children from low-income families in kindergarten through eighth grade without other requirements or restrictions. CSF National has provided more than $600 million in scholarships to more than 145,000 students. Because of their unique donor structure, 100 percent of every donation made to the program goes directly to funding a child’s attendance in a tuition-based school—a school chosen by the parent. Parents must in-turn pay $500 of their children’s education costs. CSF Baltimore has provided more than 6,000 scholarships to students to attend more than 100 schools at a cost of more than $12 million.

The “village” surrounding those students has come to include not just their parents and friends, but also the schools that educate them and that often find additional funds for the families, the team at CSFB, and the private donors who make the scholarships possible.

What has become of some of those students since they received their scholarships? How did they perform in high school? What was their post-high school experience like? In a cross-sectional survey of seven cohorts who were eligible to graduate high school by the time of the study (334 scholarship recipients in the high school class cohorts of 2008 to 2014), our firm sought to answer those questions.

Here’s what we found.

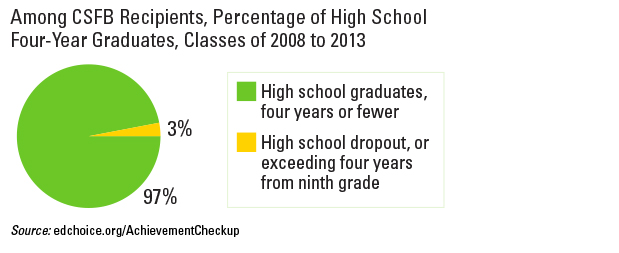

1. The CSF Baltimore scholarship recipients were graduating high school at a rate of 97 percent—a much higher rate than their peers in Baltimore public schools (between 40 and 60 percent), and a higher rate than students across Maryland (84 percent on average).

This high rate of graduation for need-based scholarship students is consistent with other CSF programs we have studied (CSF Philadelphia, CSF Charlotte, Northwest Ohio Scholarship Fund) and those that others have studied, which generally range from 95 percent to 98 percent. Not only are larger percentages of CSF Baltimore scholarship recipients graduating “on time” in four years, many are graduating “early” in fewer than four years (18 percent). Compared to the percentage of students who graduate in fewer than 4 years nationally (2.9 percent), that’s huge. (Note: CSFB survey response rate was 67 percent).

2. The CSFB alumni survey found scholarship recipients enrolled in college at a higher rate than either the Baltimore City Public School (BCPS) ninth graders or the BCPS high school graduates who were tracked in two local studies.

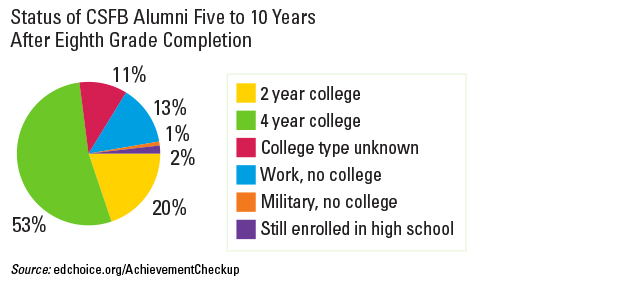

In our study, 84 percent of CSFB alumni were enrolled in some type of college five to 10 years after completing eighth grade, 2 percent were still in high school, 1 percent entered the military, and 14 percent did not attend college immediately after graduation.

Recent studies conducted by the Baltimore Education Research Consortium (BERC) found that Baltimore’s public high school graduates enrolled in two- and four-year colleges at a rate that is slightly below the national rate for low-income students, between 44 percent and 61 percent. A study by the Center for Social Organization of Schools (CSOS) followed Baltimore’s public school ninth graders and found that an average of 32 percent of the two ninth-grade classes (classes of 2009 and 2010) had enrolled in college within five years after ninth grade.

In some cases, CSFB survey responders indicated the CSFB alumni had at some point been enrolled in either a two- or four-year college but did not indicate which type. Of those for whom college type was indicated, 73 percent were enrolled in four-year colleges, and 27 percent were enrolled in two-year colleges (community colleges). By comparison, in the CSOS study, 53 percent were found to be enrolled in four-year colleges (e.g., bachelor’s degree-granting institutions) and 47 percent were found to be enrolled in two-year colleges (e.g., associate’s degree-only institutions).

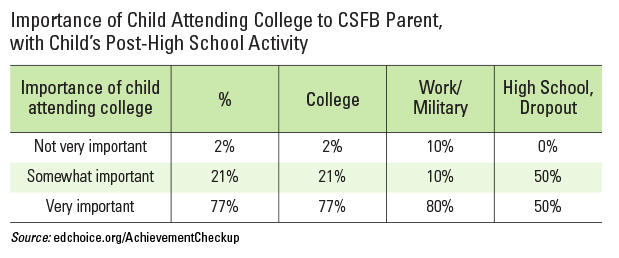

3. Overall, parents’ educational aspirations for their CSFB scholarship recipient children were very high. A number of factors are involved that mediate the relationship between a child’s educational outcomes and a parent’s educational aspirations, such as family poverty levels and the child’s intellectual talents.

The former scholarship recipients left the program and attended 61 different high schools of all kinds, including parochial schools, traditional public schools, public charter schools, secular private schools, and public magnet schools. The schools differed in their emphases on college preparation, but, for the most part, they provided a substantial amount of college preparation. After eighth grade, the parents continued to seek out and choose options that fit their desire to see their children graduate high school and attend college.

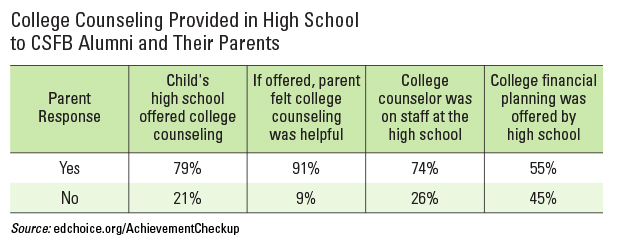

4. Our survey found 79 percent of the scholarship recipients’ high schools provided formal college counseling, although only 55 percent offered college financial counseling—a critical service for low-income families.

Our study looked at many more aspects of CSFB scholarships student outcomes, which can be examined more fully in the full report. Yet, even in the few findings presented here, we have been able to build a better understanding of a culture of low-income families that are working together with schools and supportive organizations in their communities to produce very high levels of achievement in terms of high school graduation and college attendance.

Privately-funded scholarship organizations like CSF and its affiliates are doing noble work for low-income families, but their ability to expand to reach the more than 16 million children living in povertyin America is limited. School choice programs, such as tax-credit scholarships, could greatly expand the number of low-income families who might access vital educational opportunities. In fact, 15 states are already employing such programs and seeing positive results.

Indeed, a “village” is coming together around impoverished children, and it is making a difference for their educational attainment and, very likely, their long-term socioeconomic mobility. We can say, at least, that school scholarships played a part in helping CSFB families live more than “just enough for the city”.