Educational Choice’s Blurred (Political) Lines

K–12 education can be a touchy subject. We’ve all experienced it, and many of us have children depending on it right now. Because so many of us are stakeholders in the school system’s success, debates about it can get intense, emotional and divisive.

But there are some ideas that receive support from all sorts of people. If a policy solution can meet different kinds of needs and align with different sets of values, support can cross even political party divides. Whether educational choice is one of these bipartisan issues has major implications for advocates determining political strategy.

At EdChoice, we’ve been conducting nationally representative surveys of public opinion on educational choice for years. Our annual Schooling in America (SIA) survey has tracked public opinion on educational choice policies since 2013, and it focuses on Americans’ educational priorities, satisfaction with K–12 education and opinions on educational choice policies. We also ask people taking the SIA survey whether they usually consider themselves a Republican, a Democrat, an Independent or something else. Altogether, this information makes SIA a valuable resource for learning how people of different political affiliations view educational choice and other K–12 matters.

Though we find people with different politics can have different perceptions of what problems exist in American K–12 education, we find a lot of unity behind educational choice as a policy solution.

A House Divided

How a person identifies politically heavily affects how optimistic they are about the overall direction of American education. In the SIA survey, each respondent faces a very broad question: Do you think K–12 education in the United States is headed in the right direction, or is it off on the wrong track? This question captures a person’s disposition and instincts toward American education rather than beliefs and policy preferences.

In the most recent wave, Democrats were far more optimistic about the direction of K–12 education than Republicans.

With 58 percent stating they felt K–12 education was heading in the right direction, Democrats were more optimistic in 2021 than either party has been since EdChoice began fielding SIA. In fact, Democrats in 2021 were the first group to break the 50 percent mark. Republicans, on the other hand, were the most pessimistic they have been since 2016. After peaking in 2020, when half of Republicans said they felt K–12 education was heading in the right direction, optimism plummeted to 28 percent in 2021. Together, there is a 30-point gap between Democrats and Republicans who feel good about the direction of American education, the widest gap seen in SIA’s history.

Over the eight years of SIA data, trends appeared to morph the year following a presidential election.

In 2013, the shares of Democrats and Republicans who felt positive about the direction of K–12 education were essentially the same. Through 2016, optimistic Republicans declined. Between the presidential elections of 2016 and 2020, positive Republican responses skyrocketed 35 percentage points. After the 2020 presidential race, both Democrats and Republicans shifted dramatically to produce the massive gap we see today.

Nontraditional forms of education can be especially appealing to people disillusioned with the traditional schooling system. The most recent SIA numbers indicate what some educational choice advocates have noticed, that conservative Republicans are more likely to have a pessimistic disposition toward K–12 education in the United State right now. As recently as the year prior, however, Republicans were substantially more likely to feel positive about the direction of education than Democrats. Only after the 2020 election, which saw Democrats claim the White House and the House of Representatives, did the tide pull so heavily negative again.

These findings suggest that negativity toward the K–12 education system may be at least somewhat dependent on the political climate of the time. While COVID-19 likely also plays a role in people’s perspective on education, it is notable that Republicans grew more positive about education in the first summer of COVID-19 but more pessimistic in 2021 than they had been since the Obama administration in 2016. Similarly, while Democrats were slightly less optimistic about K–12 education a few months into the pandemic, they were more positive in 2021 than they have been in any other SIA survey. While causality is impossible to determine, it seems there is more going on in the data than simply responses to COVID-19. The different political climates may have induced different responses to the pandemic.

Red or Blue, People Really Like Educational Choice

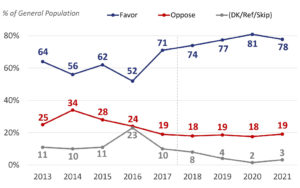

Although Democrats and Republicans can differ in their overall perception of K–12 education, they unify when it comes to educational choice policies. Each year of the SIA survey, majorities of Americans supported education savings accounts (ESAs), private school vouchers, charter schools and tax-credit scholarships (TCSs). We’ve seen record levels of support for each of these educational choice policies over the last two years. Most notably, more than three out of four (78 percent) of people supported ESAs in our 2021 SIA survey.

One might assume most of the support for educational choice to be concentrated among Republicans and most of the opposition to come from Democrats. In fact, Americans who identify on either side of the political spectrum are very likely to support each of the four private educational choice policies we present in the SIA surveys. Survey respondents who self-identify as Democrats have indicated majority support for every educational choice policy every iteration of the SIA survey.

More specifically, in the 2021 SIA survey, 83 percent of all self-identified Democrats supported ESAs. In comparison, 70 percent of self-identified Republicans supported ESAs. This survey marked the second time in three years that Democrats favored ESAs at a greater rate than Republicans.

While Republicans usually support the other forms of educational choice at greater rates than Democrats, the differences are rather small. In the 2021 SIA survey, 67 percent of Republicans and 65 percent of Democrats supported private school vouchers, 70 percent of Republicans and 69 percent of Democrats supported tax-credit scholarships, and 71 percent of Republicans and 62 percent of Democrats supported charter schools.

While bipartisan public support for educational choice—and especially ESAs—is clear, specific educational choice legislation can be more complicated.

Some educational choice programs are somewhat limited in scope (eligibility is limited to particular students), empowerment (a student receives a small amount of money relative to the money that would be spent on their traditional public education), or resources (budget restrictions or participation caps limit the number of students who could participate).

Our SIA polling finds Democrats are at least as supportive of expansive educational choice policies as their Republican counterparts.

In the SIA survey, we randomize whether participants see a statement suggesting ESAs should be “only be available to families based on financial need” (needs-based ESAs) or a statement suggesting ESAs “should be available to all families, regardless of incomes and special needs” (universal ESAs). There is minimal partisan difference on agreement for universal ESAs, with 83 percent of Democrats supporting universal ESAs compared to 80 percent of Republicans. Sixty-four percent of both Democrats and Republicans agreed that ESAs should be needs-based. With the exceptions of 2015 and 2019, Democrats have at least matched Republicans in favoring universal ESAs.

Conclusion

Education can be a sensitive topic that divides people. EdChoice’s SIA survey suggests as much when we observe split opinions on the direction of American K–12 education by political party. We do not observe the same splits with respect to educational choice. Though their reasoning could be different from each other—and while the current political climate may shape their motivations—people from both parties consistently support educational choice.

The story doesn’t end here.

Another wave of the SIA survey will be in the field this summer and is sure to teach us even more about the relationship between political parties, perceptions of American K–12 education and educational choice policies.

This is just the tip of the iceberg of what can be done with the thousands of responses we’ve received to our nationally-representative survey over the years. Have an idea of something else to do with the data or want to use it yourself? Email us at research@edchoice.org.