ESAs are Key to Improving Ed, Attracting Talent in Detroit

It has been sad to watch the spectacular fall of the once great American city of Detroit. From 1950 to the present, the population of Detroit has dropped from 1.85 million to fewer than 700,000 residents. Once home to the highest per capita income among metropolitan areas in the United States, Detroit now has:

- a 38 percent poverty rate—compared to national poverty rate of 14.5 percent,

- the highest murder rate in the nation—with 45 murders for every 100,000 residents,

- an unemployment rate over 20 percent—compared with the national unemployment rate of 5.7 percent.

- filed for bankruptcy with more than $18 billion in debt. That translates to about $26,000 in debt for every man, woman, and child in Detroit, and it is by far the largest municipal bankruptcy in American history.

Despite those seemingly insurmountable challenges, Detroit turned an important corner in recent months when the city government emerged from bankruptcy by shedding $7 billion in debt. Still, the city remains on rocky ground.

Basic services are lacking. For example, the fire department has too few arson investigators and inspectors. Despite its high crime rate, Detroit’s police presence is one-third the size of Los Angeles.’ And, according to a 2014 piece in the Detroit Free Press, 40 percent of streetlights do not work, and 40 percent of city buses are broken.

In addition to those government issues, Detroit businesses cannot find workers with the skills they need. And because of a lack of funding and coordination in transit systems, low-skilled Detroit workers find it difficult to access jobs that would allow them to earn a living and pay municipal taxes.

The local business community knows they need more wealth-producing, taxpaying residents if Detroit is going to rebound, pay its bills, and provide for its citizens’ needs:

Imagine if we could repopulate the city. But the challenges are enormous for security and schools.

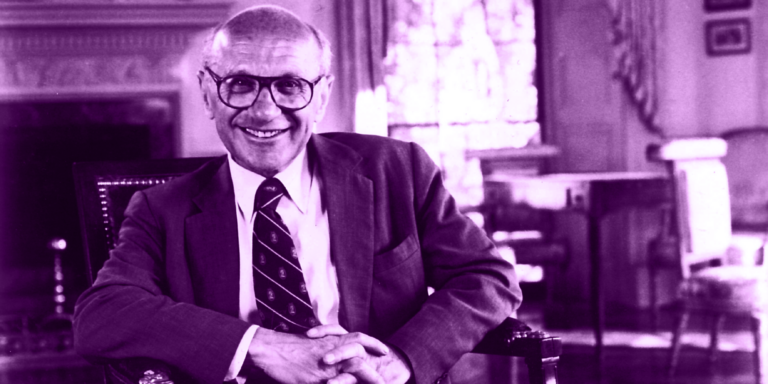

-Martin Manna, President of the Chaldean American Chamber of Commerce

Former Detroit Mayor Dave Bing agrees:

All of us want the end game to be the same thing: a safe city, a vibrant city. You get there with resources—people and money.

It’s necessary that Detroit leaders focus on improving the present economic situation for job-seeking adults. But they also must look to the future—and not in some abstract way. They can do so literally by improving the educational opportunities available to Detroit’s youth; i.e., the city’s future residents, employers, and leaders.

Sadly, one statistic tells the grim tale of the educational challenges facing Detroit going forward. According to a 2011 report funded by nine foundations plus the U.S. Department of Labor, 47 percent of Detroit adults age 25 or older are functionally illiterate. That means 47 percent of Detroit adults cannot “use reading, speaking, writing, and computational skills in everyday life situations.” The 47 percent of adults do not possess those minimal life skills are at a severe disadvantage in participating in the economy or civil society and at passing on human capital to their children.

The Cato Institute’s Andrew Coulsen highlighted the report’s devastating indictment of Detroit’s K-12 education system:

The report notes that half of the illiterate population has either a high school diploma or a GED. That’s beside the point. Virtually the entire illiterate population has completed elementary school, the level at which reading is theoretically taught. That’s seven years of schooling (K-6), at a cost of roughly $100,000 [per child], for…nothing.

Over the years, Detroit leaders have proposed myriad solutions to solve the city’s educational ills—and that clearly hasn’t worked. So, perhaps they should go in the opposite direction: Keep it simple.

Accordingly, one policy change can start to meaningfully address the city’s issues—if Detroit and Michigan leaders are willing to be bold. That policy change is called education savings accounts, or ESAs.

ESAs allow families to receive their education dollars in a government-authorized savings account or debit card with restricted, but multiple, uses. Those funds can cover any combination of learning services that fit their children’s needs. Any leftover funds can be rolled over for the next year or even saved to pay for college.

Detroit wouldn’t be alone in implementing this model for delivering public education. Arizona and Florida have already tested the waters with ESAs for limited groups. There, families are using ESAs to tailor education for their kids; families are satisfied with their experience; and the built-in accountability measures are working well to prevent misuse of ESA funds. Partly because of those programs’ success for students, legislators in Delaware, Georgia, Iowa, Montana, Nevada, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, Tennessee, and Virginia are considering creating ESA programs this year.

Here’s how ESAs could work in Detroit:

Using the most recent data available from the U.S. Department of Education, Detroit public schools spend $13,416 per student. Thus, the federal, state, and local governments could pool the funds they currently send to Detroit public schools and provide all students ESAs with an average value of $10,000 per student, with low-income children and students with special needs given proportionately more funding.

Families would use the ESAs to pay to attend private schools, virtual schools, or hybrid schools that combine on-site instruction and virtual learning. Given the high levels of social distress in Detroit, funds in ESAs could be used for other services that improve student learning, such as extra counseling, educational therapies, tutoring, speech and hearing experts, dyslexia specialists, after-school activities, and more.

Perhaps most important, ESAs would provide an incentive for new educational options to come to Detroit. For example, new private schools and specialized practices could open inexpensively in Detroit with office rents being one-third less than the state average in Michigan.

For every 10,000 existing Detroit public school students whose families chose a $10,000 ESA over Detroit public schools, Detroit taxpayers would have more than $34 million in savings that could be used for needed city services like fire, police, streetlights, and bus service. Of course, any new residents moving to Detroit for better educational opportunities available under an ESA program and very inexpensive real estate would also contribute tax revenues to city and state coffers and patronize local businesses.

To a degree, state and city leaders are already encouraging such educational growth through their promotion of charter schools. But they do not go nearly far enough. Former Democratic Mayor of Milwaukee John Norquist once highlighted in the Wall Street Journal why limited school choice does not do enough to encourage job-providing, taxpaying residents to move and live in downtown urban areas.

Remember, Detroit is already investing heavily in a K-12 education system that has resulted in a 47 percent adult illiteracy rate. Of course, its public schools are not solely responsible. But, there is a way to get a better return on the $13,416 spent each year on Detroit students: Let their families decide where to send them to school and what wraparound services their children need. A significant body of research shows that—when given that opportunity—low-income parents can and do make good educational decisions for their children.

Charter schools that must conform to national and state academic mandates can be great solutions for many kids, but are not nearly diverse enough to deal with the monumental human distress in Detroit and to entice new residents to come to a struggling city. ESAs would inspire hope by allowing for different educational and social approaches that endeavor to meet the many needs of Detroit’s culture of intense poverty.

What would it take to get middle- and upper-income families to move to Detroit? What would it take to get new and existing businesses to start or relocate in Detroit?

I propose attracting families and businesses not with new funds, but with ESAs. How about this recruiting line:

If your business comes to Detroit, all of your employees’ children would receive education savings accounts that would allow them to choose among public, private, or a combination of learning options, and save leftover funds for college.

Long-term, you will have access to a diverse hiring pool educated in a vast array of innovative public schools, charter schools, private schools, career academies, virtual schools, and more.

For parents:

Your children are unique. They have different talents and aspirations. In Detroit, your children would receive education savings accounts that would allow you to choose among public, private, virtual, blended, or a combination of learning services, and save leftover funds for college.

Long-term, Detroit is changing rapidly. When your children enter the workforce, they will have access to ever-growing and diverse employment opportunities because of the diverse and safe schooling environments in which they grew.

How does moving a business or family to Detroit sound now? Highly educated millennials want to live in cities—including Detroit. But, to get them to stay there when they have children, Detroit will have to offer them basic city services, safe neighborhoods, and choices as to where their children attend school.

The state of Michigan and the city of Detroit have excellent leadership teams that have led the city out of bankruptcy. But these leaders do not have a hidden pot of money available to save Detroit. While some may be skeptical that a universal school choice program will lead to a significant in-migration of residents to Detroit, ESAs have an advantage over most others—Detroit does not need extra money to allow parents choice over where to send their children to school, it just needs the will.

High crime, a lack of basic services, and a financially struggling city government are not going to attract new residents and jobs to Detroit—but unfettered educational choice just may.