Friday Freakout: School Choice Passes the Rotary Four-Way Test

Surprisingly, three Texas politicos recently argued that school choice policies fail all four aspects of the Rotary test. Instead, former Texas Lt. Gov. Bill Ratliff and two of his sons, Texas State Board of Education member Thomas Ratliff and Public Education Committee member Bennett Ratliff, claimed that assigned district schools are “the only answer that passes the 4-way test.”

However, an evidence-based examination of these questions yields a very different conclusion.

The Truth About Why Kids Need School Choice

The Ratliffs begin by testing the accuracy of what they claim is the central argument for school choice.

“Kids are trapped in low performing schools” is typically used as the biggest selling point for private school vouchers. Quite simply, this isn’t true. Under current Texas law and TEA rules, if a school district is ranked low performing for three years, that district’s students can transfer to any other school in the district or a nearby school district, free of charge, as long as the chosen district has space available. This program has been in place for almost 20 years and is called the Public Education Grant Program (PEG). Last year, students at 892 campuses across Texas could have transferred from their home school under this provision at no charge to the parents. How many left their district? 1,694. That’s 1.9 students per campus.

They conclude “Strike 1 on the 4-way test.”

However, the Ratliffs misconstrue the central argument for school choice. The problem isn’t that children are trapped in failing schools, it’s that they are trapped in schools that don’t work for them.

A school that is generally high performing and works well for most children might nevertheless not be a good fit for some children. Unfortunately, students are assigned to district schools based on where they live—but we shouldn’t expect any one school will be able to meet all the diverse needs of all the children who just happen to live nearby. Most low- and middle-income families are unable to afford a home in expensive districts with high-performing schools or cover full tuition at private schools, leaving them no viable option besides their assigned district school.

The Ratliffs point to the number of Texas students who transferred to other district schools as evidence that parents are satisfied with their assigned schools, but that is a poor proxy for parental demand of additional schooling options for several reasons. First, the Texas district school choice program is only limited to schools that are designated as low performing, so students in most districts don’t have access to it even if their school isn’t working for them.

Second, students assigned to failing district schools can transfer only to other district schools that are participating in the open enrollment program. And even then, as Ratliff notes, the student can transfer only if there is space available. As a Texas Tribune article found, parents who wanted to participate in the open enrollment program have discovered their options were quite limited.

Third, even assuming that parents actually know about the program and have found participating schools with open seats, the parents might see a lack of substantive difference among other district schools. In that case, they may decide to keep their children closer to home.

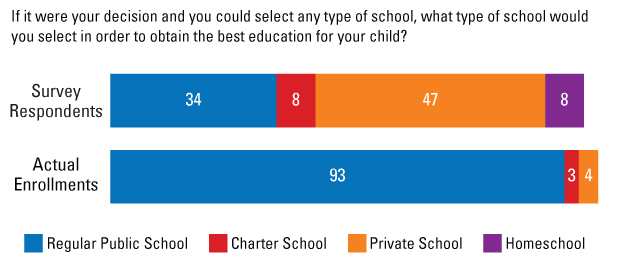

To measure parental demand for additional educational options in a system that lacks school choice, it’s best to ask parents directly. Fortunately, in a 2013 survey of a representative sample of Texans, the Friedman Foundation did just that. When asked what type of school they would prefer for their children, 47 percent of Texas parents responded that they would choose a private school first. However, only 4 percent of Texas students actually attend private school, indicating more than 4 in 10 families would like to send their children to a private school but are unable to do so.

It’s no wonder then that 75 percent of Texan parents surveyed expressed support for tax-credit scholarships and 71 percent supported education savings accounts.

The truth is parents want more educational options for their children.

School Choice Is Fair to All Concerned

The Ratliffs claim school choice also fails the Rotary’s fairness test:

“If two students are given a $6,000-$8,000 voucher to take to the school of their choice, do they both have the same opportunity to use that voucher? The short answer is ‘no,’ they don’t.”

They point to the differences in the “economic resources available” to different families—but this is evidence that life tends to be unfair, not that school choice isn’t fair. Indeed, traditional district schools would certainly not pass the Ratliff interpretation of the Rotary’s fairness test because students from well-off families can afford to live in higher-performing districts than low-income students.

And it’s not funding that’s the issue, otherwise, at $30,000 per pupil, Washington D.C.’s district schools would be achieving the best proficiency scores in the country instead of some of the worst. Wealthier parents have other options, so schools have to be responsive to their needs or they will vote with their feet. Lower-income families are a captive audience.

School choice policies cannot eliminate all of life’s inequalities, but they vastly expand the opportunities available to the most disadvantaged children relative to the current establishment.

School Choice Fosters Goodwill and Strengthens Communities

Based on their mistaken assumption that school choice policies would widen inequality rather than narrow it, the Ratliffs then err in concluding such policies fail the Rotary’s third test:

“While the smart, rich kids use their voucher to go to the elite private academy of their choice, those with special needs, economic limitations or other barriers have no choice. How will that build good will [sic] or better friendships?”

Yet again, we must consider the outcome of school choice policies against the backdrop of the status quo. Rich and poor kids are currently segregated in different districts based on the homes their parents can afford. They are also segregated along racial lines. In 2012, the New York Times reported “43 percent of Latinos and 38 percent of blacks attend schools where fewer than 10 percent of their classmates are white.”

By breaking the link between education and housing, school choice promotes greater racial integration. The evidence is overwhelming:

Eight empirical studies have examined school choice and racial segregation in schools. Of these, seven find that school choice moves students from more segregated schools into less segregated schools. One finds no net effect on segregation from school choice. No empirical study has found that choice increases racial segregation.

Not only did they ignore the context and the evidence regarding the impact of school choice on racial integration, the Ratliffs also ignored the central question: What sort of education system best fosters goodwill?

In the public school system, decisions are made via a political process that produces winners and losers—and in that system, minorities sadly tend to be the ones who lose. As my colleague Neal McCluskey has observed, “Public schooling politics is a zero-sum game: all people pay in, but only those with political power get control.”

Familiarizing oneself with the history of American education makes clear just how divisive public schooling has been. For instance, see the Philadelphia “Bible Riots” or the textbook war in Kanawha County, WV. And just because something is local- or state-controlled doesn’t free it from conflict. Cato’s still-under-construction public schooling “battle map” pinpoints well over 800—and growing—contemporary battles over basic values and rights fought at the school, district, and state levels. And that doesn’t include constant combat over budgets, teacher evaluations, school start times, math curricula, and on and on.

Ultimately, understanding why public schools are the source of unceasing conflict—and why it worsens the more that control is centralized—requires the simplest of logic: One government school system cannot possibly serve all, diverse people equally.

By contrast, a system of school choice empowers every parent to choose the school that aligns with their values and meets their children’s needs. When parents with different views about education can choose different schools, they have no need to fight with each other over what their schools teach. That may partially explain why students participating in school choice programs have been found to be more politically tolerant.

School Choice Is Beneficial to All Concerned

When considering the Rotary’s fourth test, the Ratliffs oddly focus primarily on the pay gap between teachers at Texas district schools and charter schools. But in a system of true educational choice, teachers could also find great opportunity. For example, one “rock star” teacher in South Korea’s vibrant education market earns more than $4 million a year. They also ignore a key factor: If teachers don’t want to work at a school that offers lower salaries, they don’t have to accept a job there. If that school leader can’t find any good, quality teachers to accept an offer, he or she will likely sweeten the offer by increasing pay or benefits.

Eventually, the Ratliffs return to the impact on children, where they assert school choice would harm those who are “left behind” at the district schools:

So, based on these facts, the bottom line question is, “Would vouchers be beneficial to all concerned?” The answer is decidedly “no, only a small handful of students might benefit, and many of those left out could find their schools negatively affected by the diversion of taxpayer funds to elite private academies.”

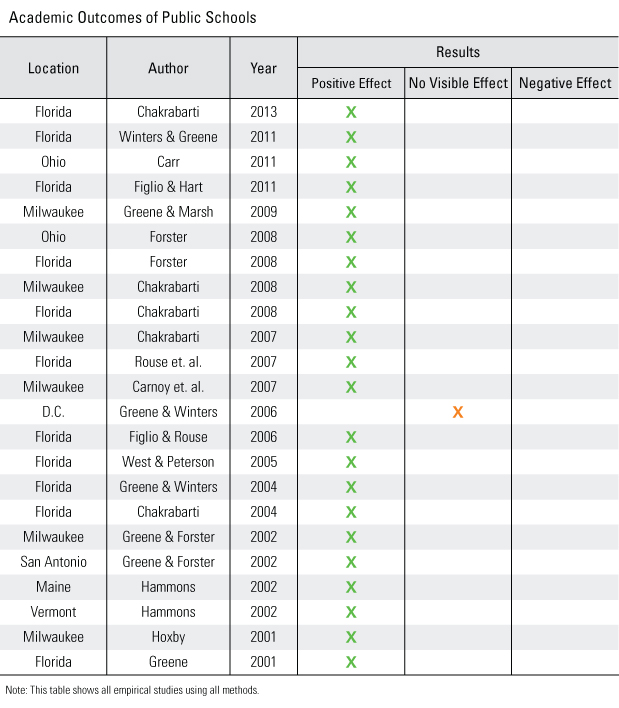

Again, however, the evidence tells a different story. Not only do students participating in school choice programs benefit, but so do the students attending the district schools that now feel a bit more pressure to compete for students.

Schools that have a captive audience of families don’t have to work hard to meet their students’ needs to keep them. After all, those families can’t walk out. But when families have the means to choose to send their children elsewhere, those schools have to be responsive or risk losing them. By empowering families with an exit option, school choice policies benefit both the students who leave and those who remain in the district school.

School Choice Passes the Rotary Four-Way Test with Flying Colors

The evidence is clear: School choice policies do a better job being fair to all, building goodwill, fostering better friendships, and benefitting all concerned than the ZIP Code-based, one-size-fits-some status quo that still exists in most of the country. Let us hope that upon studying the evidence, the Ratliffs will revise their position on school choice. After all, the Rotary’s first test demands we honor the truth.