Why Shaming School Choice Parents Will Hurt Your Community

I find myself this year in the interesting position of kindergarten shopping for my 5-year-old daughter. Besides the expected “I can’t believe she’s this big already” nostalgia, there’s an element of confusion—even angst—as we try to find her best educational fit.

This does not stem from a lack of good choices. We have at least five options, including public magnets, a charter, a private school and even our neighborhood school, that could work well. My personal struggle is balancing the line between giving my daughter the absolute best and being an integral part of my largely low-income community.

I believe in educational choice for all kids. But I also know there are many kids in my neighborhood whose families can’t yet make these choices. They might not know all the options available or be able to provide transportation, and there are not enough seats at the district’s “highest-performing” schools, even in the choice-rich environment of Indianapolis, the capital of a state once dubbed the “reformiest” in the nation.

Perhaps that’s why a recent New York Times article resonated so much with me, despite my disagreement with many of the author’s points. In it, Nikole Hannah-Jones writes, “Democracy works only if those who have the money or the power to opt out of public things choose instead to opt in for the common good. It’s called a social contract . . .”

I believe in this social contract and in acting for the common good. It’s why my family moved to a developing part of town and renovated a home on a block filled with crumbling duplexes. It’s why we send our kids to a local daycare, where racial and economic integration is key. And it’s why we’re striving to find a diverse local school for our soon-to-be kindergartener.

Hannah-Jones is right that investing in the public good is essential for the wellbeing of any community. But when it comes to education, I disagree that only funding traditional district schools is the singular way to do that.

Hannah-Jones writes that “the guiding values of public institutions, of the public good, are equality and justice.” But this isn’t always or only true of public institutions. Segregation and resource-inequality are huge issues in the Indianapolis Public Schools. Yes, the district is working to remedy those problems. But one local private school beat the district to the punch when it comes to both economic and racial integration.

The fundamental problem with Hannah-Jones’ argument is highlighted in the final paragraph of her opinion piece: “If there is hope for a renewal of our belief in public institutions and a common good, it may reside in the public schools. Nine of 10 children attend one, a rate of participation that few, if any, other public bodies can claim, and schools, as segregated as many are, remain one of the few institutions where Americans of different classes and races mix.”

There are three flaws with her logic.

The “Community” Paradox

The first falsehood in Hannah-Jones’ reasoning is that to believe in a common good, one must also believe in public institutions as the sole contributors to the common good. The idea that families who live in a district but opt out of its school are not invested in their community is ludicrous for two reasons. 1. Private schools and charter schools are not islands. They’re part of a community, and they contribute to the common good, too, by educating children and future citizens. And 2. No one has the right, or the power, to define what “community” means and doesn’t mean for another person.

We see families across the nation, especially in states with robust choice programs, who are deeply invested in their non-public schools. Many are not wealthy, as the author suggests, but they find in their experience a richness of community and a commitment to a shared mission.

Indeed, we know from our research that private school parents become more involved in a variety of activities, including communicating with teachers, participating in school activities and volunteering and community service.

I would argue that the ability to choose—not the type of school chosen—is what drives investment in a school and community.

Many of my friends in our neighborhood send their kids to downtown magnet schools, which adds significant time to their commutes. At least five families have chosen to opt out altogether by homeschooling their kids. A few send their kids to private school. They are all committed to those choices, and their schools benefit from that commitment.

The “Enrollment = Demand” Fallacy

The second flaw is one that’s even more easily disprovable with data: her reasoning that we must believe in public schools as an institution because they are well attended.

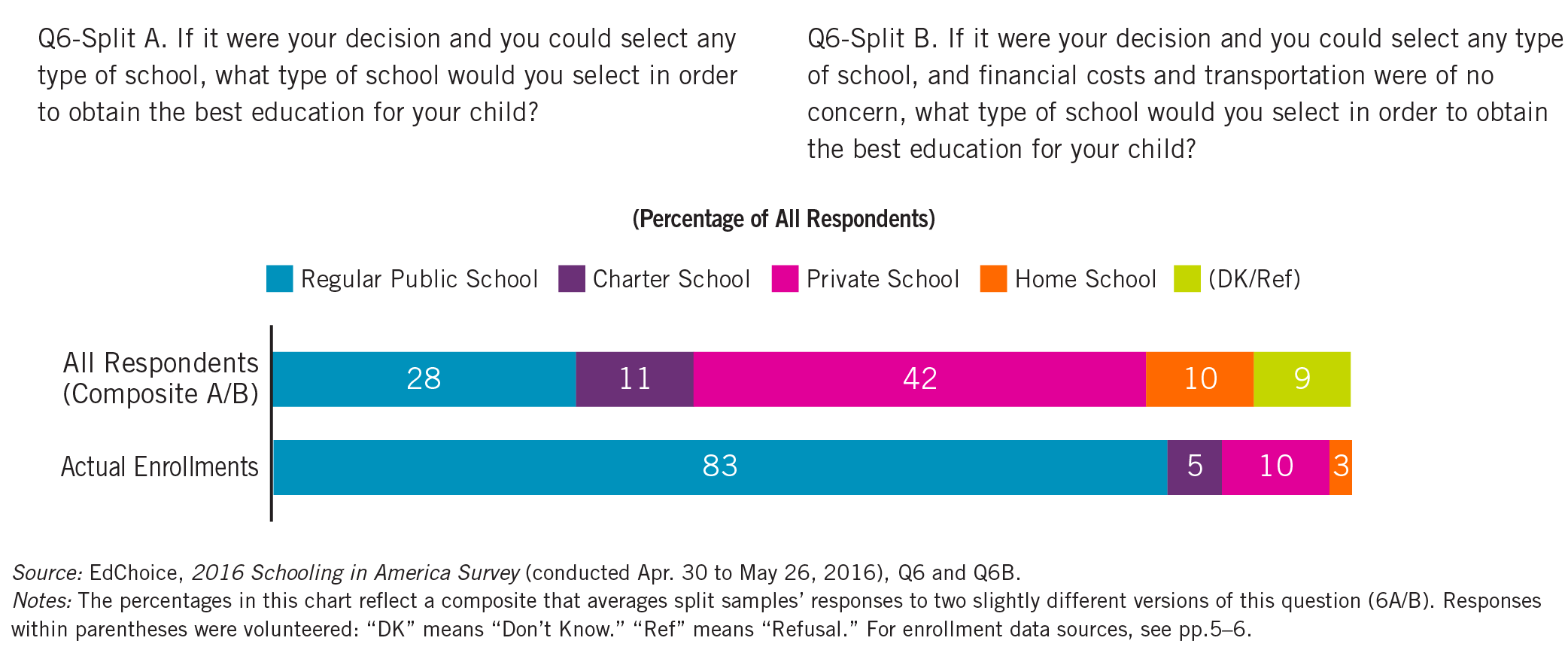

It’s true that 83 percent of students attend traditional public schools, but—unlike many other public goods, such as libraries, parks and beaches—that’s not entirely by choice. Far fewer would do so if there were fewer obstacles in their way. When asked about their preferred school type, 41 percent of American school parents prefer a private school; only 28 percent would choose a public district school; 17 percent would choose a charter school; and 11 percent would home school.

The “Public Schools Are Inclusive” Assumption

The third flaw is thinking that school choice can’t also open doors for races and classes to mix.

The truth is public school families have used a form of school choice: buying a home in a different district. Parents who start raising children in urban areas may move to the suburbs as soon as their children are ready for school. They are effectively buying their way into higher-performing schools, and those schools are part of a system that sanctions barring the door to families who can’t do the same.

Every study ever conducted on school choice programs in America has found they improve integration by allowing children to move from more segregated schools to more integrated schools. That bodes well for a system where all families can choose.

Furthermore, if the goal is more people investing in turning around our struggling public schools, reverting to a choice-less system where your ZIP Code is king isn’t the way to make that happen.

A look at Census Bureau statistics backs this up: “[In] 2011, children between ages 5 and 14 constituted 7 percent in urban core Central Business Districts (CBDs) across the country, less than half the level in newer suburbs and exurbs.” So even if all families were required to send their children to traditional public schools, rather than availing themselves of charter, private and home school options, many families still wouldn’t invest in what they see as “failing” schools.

As upcoming EdChoice research shows, innovative options like arts-based charter schools may actually attract suburban families to re-invest in urban communities, whether by dining at local restaurants after school functions or even moving back into the city to be nearer to their school of choice.

What Will Our Family Choose?

As we find ourselves now in choosing mode, we must consider the options available to us—and what’s best for our daughter.

Our zoned public school has been struggling to meet the needs of its students, but local community leaders want to help. The proposal would allow the neighborhood to take control of the school through a newly formed nonprofit. That would give school and community leaders micro-control over every detail of the school—from finances to curriculum to hiring—while leaving the school under the local school board.

The plan would put more teachers in classrooms and add social support services to the school, which struggles to meet the needs of students from families that move often, many of whom are non-native English speakers. The school wants to increase parent engagement, have a longer school year and help families as a whole.

It’s a beautiful vision, full of the “equality and justice” Hannah-Jones lauds. And if the school board allows the plan to go through, we’re considering sending our daughter to the school. After all, we moved to the area to help improve the neighborhood. And what better way to do that than by getting involved in our local school?

But here’s the thing: If we opt in to this school, we do so with the knowledge that we can opt out later if it doesn’t work for us. We could choose to move to a magnet or charter school next year. We could slash our expenses to pay for a private school. One of us could quit our job to homeschool. We have options, and that empowers us. Every family in America should have access to those same options. For many, school choice programs are the only way to ensure all doors—not just one out of three—are open to their children.

But even if we never enroll in our public school, we’ll still get involved. After all, supporting school choice programs and helping improve our zoned public school aren’t mutually exclusive options. I will do both in my community because education—not just one school or type of school—is for the public good. School choice is about creating a whole new system in which all families are empowered to make choices—whether that’s a traditional public school, a charter, a private school, a home school or a combination of all these options.

If you find yourself responding, “But if we just fix the public schools, no one will need school choice,” you’re certainly not alone. It’s a nice thought. But it’s not a realistic one.

For one thing, even the perfect neighborhood school won’t be able to meet the individual needs of every kid in its catchment zone. Kids’ interests and learning styles are just too diverse. If you need evidence of that, just look to the highest-performing district in your area. You’ll still find families who opt for private, charter or home school education because those options better fit the needs of their children.

And think of the message that “we need to make all public schools great” sends to parents like me who are making decisions for their children’s education right now. We don’t have time for the community and its politicians to eventually agree to fix schools. We can’t waste our children’s limited school years waiting for the dust to settle as districts finally implement real changes. Our kids’ futures are on the line.

That kind of uncertainty isn’t good enough for my kid. Would it be good enough for yours?