How Nevada’s Pension Structure is Hurting Teachers, Taxpayers—and What Can Be Done to Fix It

This is the second in a two-part series on Nevada’s fiscal climate and educational choice.

This is the second in a two-part series on Nevada’s fiscal climate and educational choice.

In the first part of our series, we examined the fiscal effect of Nevada’s educational savings account (ESA) program, finding that schools could save almost $700,000 for every $1 million spent funding ESAs for Nevada students.

This is a clear financial benefit for schools that no longer have to educate students utilizing ESAs, but it does little to remedy the underlying financial problems the state faces with respect to funding its education system. We turn now to those issues in the second part of our series.

Like many states in the nation, Nevada is struggling to meet its future obligations to public employees, including public school teachers, and the alarm has been sounding for some time.

Unfortunately, these challenges are having a negative effect on large public school districts.

Between what is owed to the pension systems that cover teachers and the assets they have on hand to pay what’s owed, the states faced a deficit of $500 billion in 2014—an increase of $100 billion over the prior two years. The median pension plan has 67 cents set aside for each dollar it owes for benefits. In Nevada itself, pension debt for the Public Employees Retirement System (PERS) is $12.5 billion, or $27,750 per student. This debt has increased five-fold since 2000.

Though there is much debate surrounding the sustainability and viability of public pension systems, one thing is certain: Costs are rising as Baby Boomers continue to enter retirement. University of Arkansas economist Bob Costrell estimated that per-pupil school pension costs alone have doubled nationally in the last 10 years—from $500 per pupil to more than $1,000 per pupil.

There is a common misperception that teachers and other public employees receive “gold-plated” or “Cadillac” pensions. In reality, most teachers leave before reaching retirement eligibility and wind up contributing more than what their pension benefit is worth. Teachers provide an invaluable public service educating our children, and all teachers deserve access to a retirement plan that is secure, sustainable, and works for all teachers.

States such as Nevada will be hard pressed to find ways to pay for these promises.

Final-salary defined benefit plans like Nevada’s create political incentives that lead to substantial underfunding. Most of the nation’s public school teachers (about 87 percent) are covered by these plans. Nevada’s pension plan is typical. In Nevada, teachers’ benefits are defined by an accrual factor (2.5 percent), the number of years he or she works, and the average of his or her final three years of salaries.

Incentives for politicians and long-run costs are poorly aligned. Pension costs for new employees usually do not emerge until decades later, when employees separate from service and start collecting retirement. The professional careers of politicians tend to be much shorter. Consequently, massive pension debt tends to emerge much later as a result of deals made decades earlier.

Despite balanced budget requirements, states are carrying substantial magnitudes of pension debt. The technical term for this debt is unfunded actuarial accrued liabilities, or unfunded liabilities, which refers to the amount owed in pension benefits in excess of the assets on hand to make those benefit payments. Depending on assumptions about the rate of return on a plan’s investments (the discount rate), the national estimate of unfunded liabilities for public pension plans ranges from $1.38 trillion to $4.43 trillion.

Of course, governments don’t have to pay this debt all at once—common practice is to amortize it, making periodic payments. What is certain is that paying down this pension debt will require raising pension costs. That means in order to meet their obligations, plans will need to either increase employer contributions (by increasing taxes), increase teacher contributions, divert funds from other areas of public service (by “crowding out” funding for those services) or some combination of these actions. If no changes are made, the state will have to continue robbing Peter to pay Paul by giving less generous pension benefits to new generations of teachers to alleviate the state’s existing pension debt.

In this piece, we break down Nevada’s pension costs and offer a few solutions that might improve the fiscal health of the state and school districts.

How Teacher Pension Benefits are Funded in Nevada

Pensions for an individual teacher are funded by annual payments made by the teacher (employee) and the state and/or teacher’s school district (employer). Nevada provides its public employees two kinds of cost-sharing plans.

In the “Employee/Employer Pay” plan, school district and teacher contribution rates are equally shared (Nevada statute NRS 286.410). School districts pay the entire portion of employer contributions for teachers, and districts get the money to pay out those benefits from students’ per-pupil education funds. When teachers separate from service, they may have the option of receiving a refund of their contributions instead of receiving a pension if they are vested (have been in the plan a minimum number of years).

Alternatively, under the “Employer-pay” plan, school districts pay the full contribution rate. To make this plan cost-equivalent to the shared cost plan, a teacher’s base salary will be reduced by an amount equal to half of the district contribution rate. Thus, while a teacher does not make contributions directly to the plan, per se, they forego a certain amount of wages that equals exactly one-half of the full contribution rate. Think of this as an “implicit contribution” by teachers. For example, if a district pays 26 percent of payroll on behalf of a teacher in a given year, then the salary it pays this teacher under the Employer-pay plan will be reduced by 13 percent at base that year.

Final average salary—one of the components of a teacher’s retirement benefit—will be increased by half the total contributions made by school districts. In other words, although a teacher in the Employer-pay plan is paid a lower salary in lieu of not making contributions into the plan, their retirement benefit will not be based on this lower salary. Rather, it will be computed as if a teacher was enrolled in the Employee/Employer Pay plan. It follows that the two plans are cost-equivalent for teachers.

Breaking Down Nevada’s Pension Costs

The statutory contribution rates are close to the actuarially required contributions (ARC).

That means what districts and teachers are required by law to contribute to their pension plans is close to the amount necessary to amortize pension debt over a fixed number of years (usually 30 years). In fiscal year (FY) 2014, the statutory contribution rate under the Employer-pay plan for school districts was 25.75 percent, while the total ARC rate was 27.99 percent. Thus, there was a deficiency in contributions required to fully amortize all pension debt.

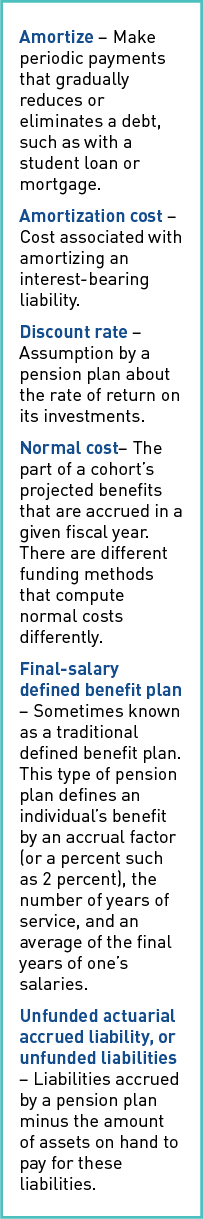

Figure 1 below presents the breakdown of the total statutory contribution rates for teachers and districts under the Employer-Pay plan over time. It demonstrates the rising contribution requirements among teachers and school districts. The magenta line illustrates the total cost of the plan; it depicts the statutory contribution rate for school districts. The blue bars and turquoise bars are equal in size for each year and represent what a district contributes on net, and what a teacher contributes implicitly in the form of lower wages.

Sources: NV PERS actuarial valuation reports, respective years

Costs for teachers and districts have increased by almost 40 percent since 2002.

In FY 2002, the full contribution rate was 18.75 percent—the teachers’ implicit contribution rate and the net district contribution rate were 9.4 percent each. By FY 2014, these rates each increased to 12.9 percent. To put it in context, a teacher with a $50,000 base salary in 2014 would have implicitly “paid” $1,750 more in foregone wages that year than a teacher with the same base salary in 2002.

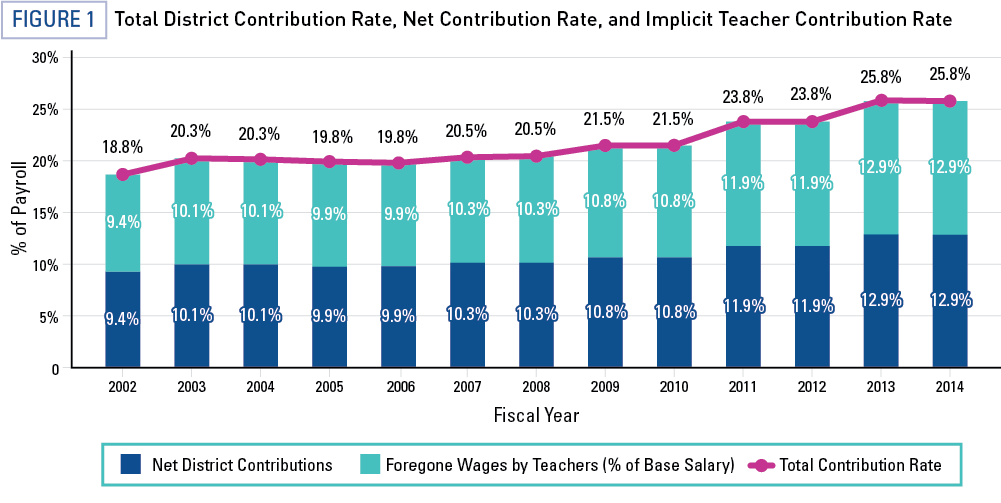

A growing portion of these teacher and district pension costs, however, has been steered toward paying off pension debt. This represents an opportunity cost to school districts increasing funds that must go toward paying down pension debt but that could have been used for other things directly related to student learning. We can observe this shift in Figure 2, which further deconstructs employer pension costs into two additional and distinct costs: the employer normal cost and the amortization cost.

Normal costs are the funds needed to pay for projected pension benefits earned by the cohort of teachers in a given year (i.e. they represent the cost of pension benefits allocated to a given year). The employer normal cost is the total normal cost minus the teachers’ implicit cost. Amortization costs reflect payments required to pay for all pension debt, repaid over a certain period (typically 30 years, as currently with Nevada). These costs combined reflect a district’s net (or direct) pension costs.

Source: Author’s calculations based on Comprehensive Annual Financial Reports for NVPERS for fiscal years 2002 to 2014

One telling sign of increasing strain on a system is whether payments to amortize pension debt make up a growing portion of employer contributions.

In FY 2002, the net contribution rate for districts was 9.4 percent, and the rate needed to pay off the pension debt over 30 years was 4.59 percent. Thus, the amortization requirement made up about 40 percent of total district contributions. This share nearly doubled over 12 years, to 74 percent of employer costs in FY 2014.

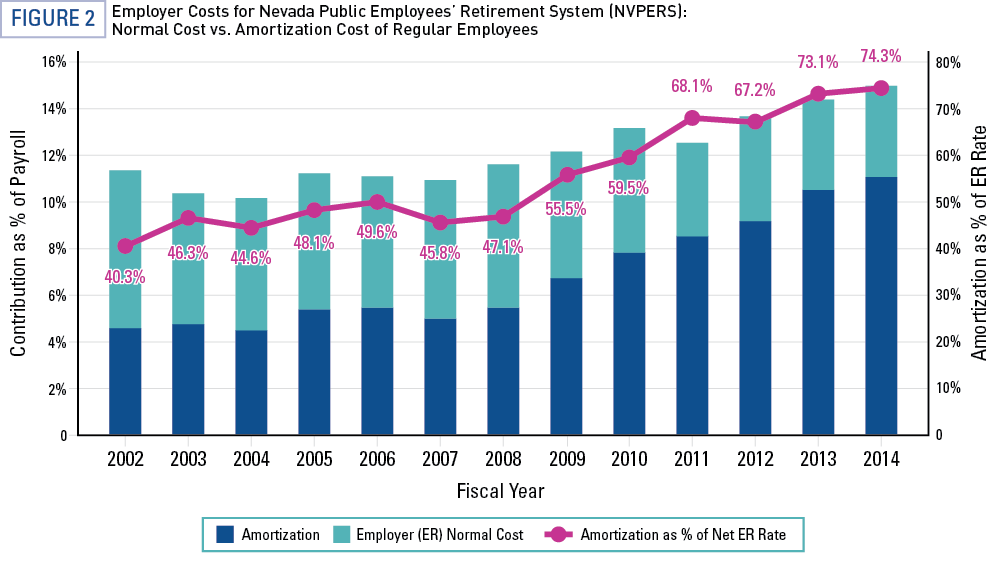

Annual payments devoted to paying off pension debt over this period, in per-student terms, doubled from $540 per student in FY 2002 to $1,189 per student in FY 2014 (Figure 3). That could mean districts are spending $649 more per child to pay off debt rather than spending it on instruction in the classroom today.

Total amortization payments ($537 million for FY 2014) have increased by an exceedingly greater rate than all normal costs over this period—267 percent compared to just 53 percent. Rising pension costs are being driven in large part by growing pension debt and reflect obligations that Nevada and its school districts must find ways to pay.

Source: Comprehensive Annual Financial Reports for NVPERS for fiscal years 2002 to 2014

Author’s calculations based on Comprehensive Annual Financial Reports for NVPERS for fiscal years 2002 to 2014 and enrollment data from the National Center for Education Statistics and Nevada Department of Education

Nevada government officials will need to fulfill the state’s fiscal responsibilities. Though pension system reform is widely debated, it may not be enough to meet obligations without having to take other action, such as raising taxes and teacher contributions or reducing funding for other public services.

For instance, reforms enacted in other states have tended to affect only teachers hired after reform is enacted and do not affect benefits that have already been earned (the so-called legacy costs). This kind of reform typically leaves newer teachers with fewer benefits than those who have been in the classroom for longer periods of time. In some cases, the differences can be quite dramatic. Illinois provides a cautionary tale for Nevada (see Figure 5 of this paper).

Possible Solutions to Nevada’s Pension Debt Problem

There are at least two things Nevada can do to directly address its pension debt challenges.

First, a very good first step toward a more sustainable system would include enacting a plan that ties contributions directly to benefits. This will stop the bleeding of increasingly accruing pension debt.

Second, the state should set contributions to the actuarially required amounts each year. Not doing so exposes future generations to greater risk that they will bear the burden of funding these systems.

Finally, as we explored in the first part of this series, expanding school choice offers a complementary path to increased financial stability. For every $1 million spent to fund Nevada’s ESA program, school districts, on average, would save about $700,000. That’s money that could be returned to the classroom to replenish per-pupil funds that currently are being spent to alleviate pension debt. To be clear, although an ESA program is not going to solve any state’s fiscal troubles, it can nonetheless free up resources that could be directed to the classrooms.

There is a common misperception that teachers and other public employees receive “gold-plated” or “Cadillac” pensions. In reality, most teachers leave before reaching retirement eligibility and wind up contributing more than what their pension benefit is worth. Teachers provide an invaluable public service educating our children, and all teachers deserve access to a retirement plan that is secure, sustainable, and works for all teachers.

Though these solutions may be difficult to execute, the Silver State must harness the willpower necessary to deal with these challenges to ensure financial stability and have a system that works for all teachers.

Read the first installment of this series, The Fiscal Impact of Nevada’s ESA Program, to learn how Nevada’s ESA program can help the state’s fiscal health.