Parents of School-age Kids Need Tech Support

We all know the cliches about the coronavirus pandemic. It was “disruptive.” It “changed everything overnight.” It “highlighted existing inequities.” And on and on.

But sometimes, cliches are cliches for a reason. The pandemic was disruptive. It did change everything (almost) overnight. It did highlight existing inequities. Just because we’ve heard people say it a million times doesn’t mean that it isn’t true.

Good research can burrow past cliches and into more detailed and interesting patterns and experiences. A new paper from scholars at my alma mater St. Louis University (Go Bilikens!) and the University of Missouri (I am ambivalent about the Tigers!) interviewed African-American parents in the rural Midwest to better understand their experiences during the pandemic.

Interestingly, the respondents had mixed feelings about, well, almost everything. They very clearly saw both the upsides and downsides of social media, videoconferencing, and the other technologies that dominated socially distanced life. The parents were happy to be able to order food online and connect with their friends, family and faith communities virtually, but also saw and felt burnout from too much screen time. One quote from the authors stuck out to me:

“Prior to the pandemic, parents were tasked with reducing screen time for their kids and involving them in more physical activity []. In a pandemic world, however, parents were not only tasked with ‘reversing’ that messaging but also becoming more involved with technology themselves and for their kids.”

Talk about a whipsaw!

The overriding feeling of parents interviewed was that they were left to “sink or swim.” Sure, lots of online resources are available, but how do you find them? How do you curate them to separate the good stuff from the bad? Sure, we can connect via videoconference or social media, but what happens when everyone wants to get on the WiFi all at once? How do you prioritize who gets the bandwidth? How can parents manage the interpersonal conflict that inevitably arises? Sure, there are great learning opportunities online, but how do parents draw the line between learning time and leisure time on the internet? How do they know when there has been too much screen time?

The authors also identified some straightforward limitations like internet connectivity and devices.

While students had access to both at school, it was more of a struggle at home. Parents also admitted that they lacked the technical training to troubleshoot problems and couldn’t help when devices failed or the internet stopped working.

Now, the study has its limitations. The total sample was only 11 parents. They were, admittedly, not drawn randomly. So it is inappropriate to generalize the findings too much. It is quite possible that different families had different experiences and that these families were outliers.

That said, what the authors find resonates with the anecdotes and stories that many of us have been hearing for months. We’ve been on calls with co-workers whose video feed is choppy because their children are trying to videoconference at the same time. Debates around screen time have been had around many kitchen tables. Sibling conflict driven by social isolation and limited phones, tablets, or computers was rife.

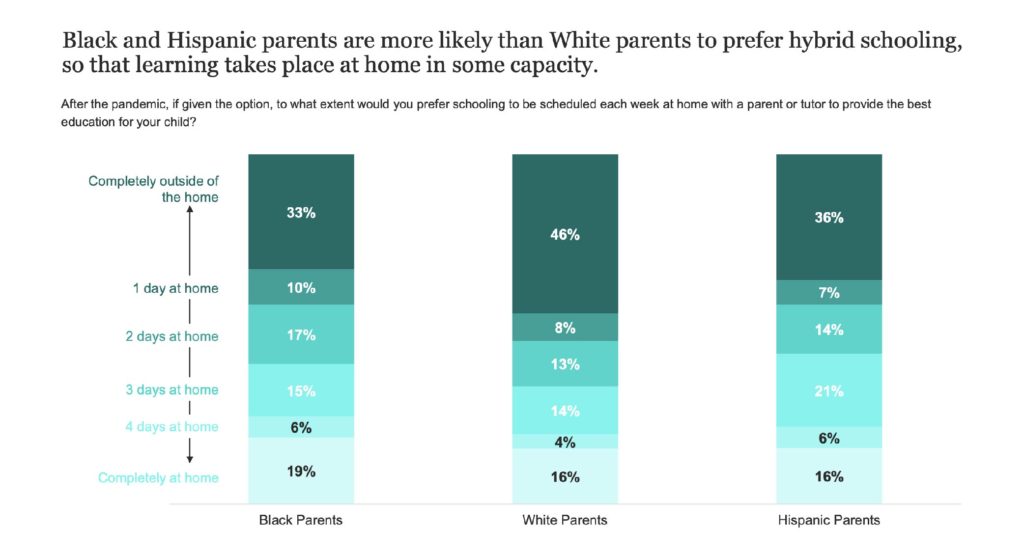

According to our polling data, a substantial portion of parents, and an ever larger proportion of Black parents, would like to have some kind of hybrid learning schedule going forward. In total, 19 percent of Black parents would like to homeschool full time, while another 48 percent would like to have their children spend at least one day per week at home. This is more than white parents, 16 percent of whom would like to homeschool full time, and 39 percent of whom would like to have their children spend at least one day at home.

If that is going to be the case, internet infrastructure is going to be critical. If families have multiple children at home on Zoom, YouTube, Google Classroom and any of the myriad other online resources at once, that is going to eat up bandwidth pretty quickly. (As an aside, I’m bullish on Starlink to solve many of these problems for rural communities, but it is not quite ready for primetime just yet.)

Schools cannot expect families to simply figure it out. Bandwidth availability should be a key consideration when thinking about future policies and practices.

A (hopefully) once-in-a-generation pandemic is a situation in which everyone, in some facet of their life or another, is going to have to sink or swim. Everyone is an expert in hindsight, but a more fruitful use of energy is to look forward, learn lessons from the pandemic, and apply them both for disaster preparation and for changing schooling in ways that can better meet the needs of children. Understanding families’ experiences of the pandemic is a great place to start the discussion.