Public Opinion Tracker: Teacher Survey Top Takeaways Q1 2021

In March 2020, schools across the country suddenly shut their doors in response to the rapidly developing COVID-19 pandemic. One year later, COVID-19 safety measures have been crafted and revised, vaccine distribution has accelerated, and the number of schools reopened or looking to reopen soon keeps growing. In the political debates around school reopening, the opinions, preferences, and needs of teachers have been utilized by unions, school administrators, and parents to support their policy desires.

In addition to our regular monthly polling of the general public and parents, EdChoice surveys teachers each quarter, and in March, we asked about their perspectives on COVID-19, how public institutions are handling the pandemic, school choice policies, and many more topics. It turns out, when you ask actual teachers, you might get different answers than popular narratives might predict. The most recent survey was conducted March 11-24 from a national sample of 1,000 teachers living in the United States and the District of Columbia. In this post, we break down the results from that survey alongside the results from parents in our March wave of the monthly tracker.

You can browse the full reports as well as our national and state dashboards, which illustrate public opinion on various educational issues at the beginning of the new year, at the EdChoice Public Opinion Tracker.

In a nutshell:

Teachers express more comfort with in-person education right now than parents. Like parents, however, teachers are open to alternative and flexible education options being offered to students long-term. In fact, large shares of teachers indicate that they would be interested in using a hybrid schedule or teaching in microschools. When it comes to progress during the pandemic, parents are more optimistic about their children’s development than teachers are about their students, as teachers are 15 percentage points less likely to consider their students progressing “very well” than parents. Teachers, especially private and charter school teachers, indicate an interest in teaching in “learning pods.” Perhaps most notable in this survey are the estimates teachers give for public school funding and teacher pay—both came in lower than what parents and the general public estimated and much lower than actual funding levels. While lower than parents and the general public, support among teachers for school choice policies are fairly high, especially for education savings accounts.

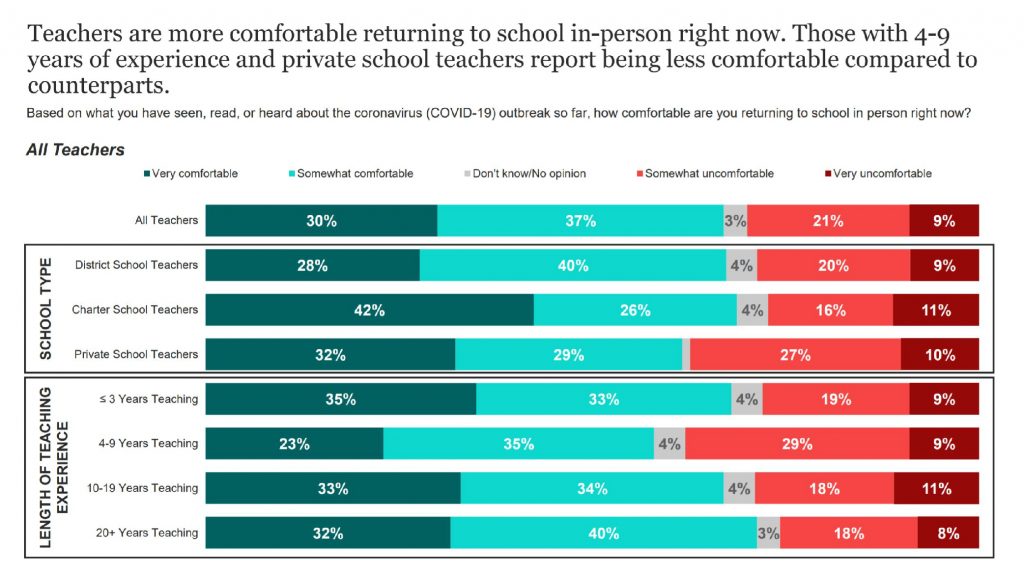

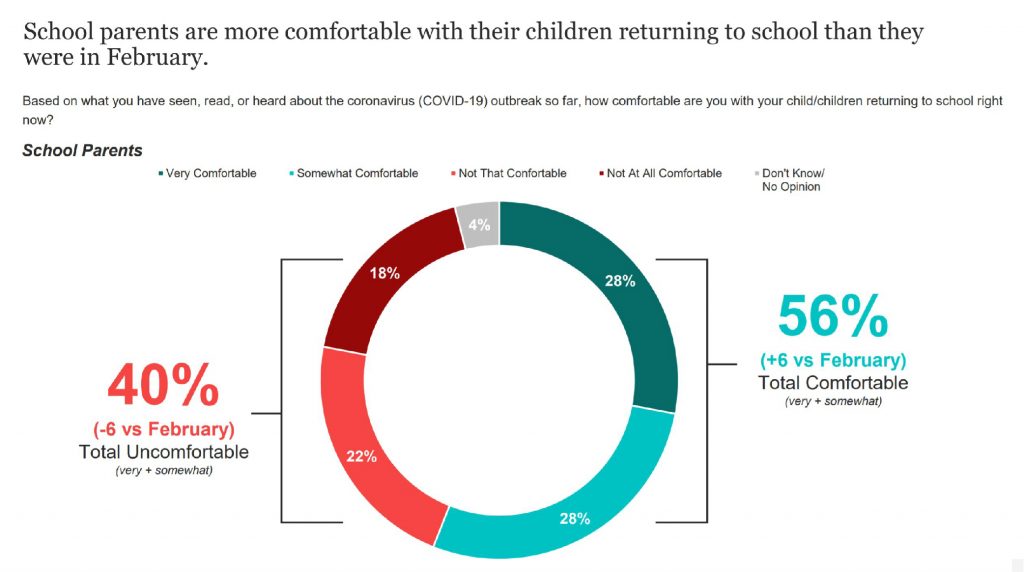

1. Teachers are more optimistic about the current suitability of in-person education than parents. Two out of three teachers are at least somewhat comfortable with schools returning to in-person learning right now. In comparison, just 56 percent of school parents currently are comfortable with in-person education, though that share has jumped substantially since the beginning of the year. Private school teachers are notably less likely than public district or charter school teachers to be comfortable with in-person schooling, though a clear majority still are favorable toward it.

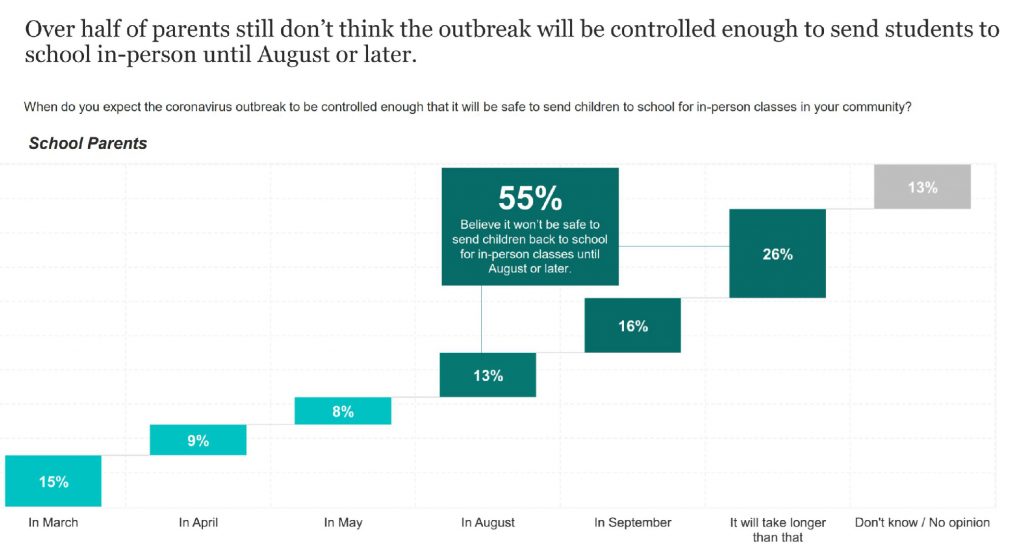

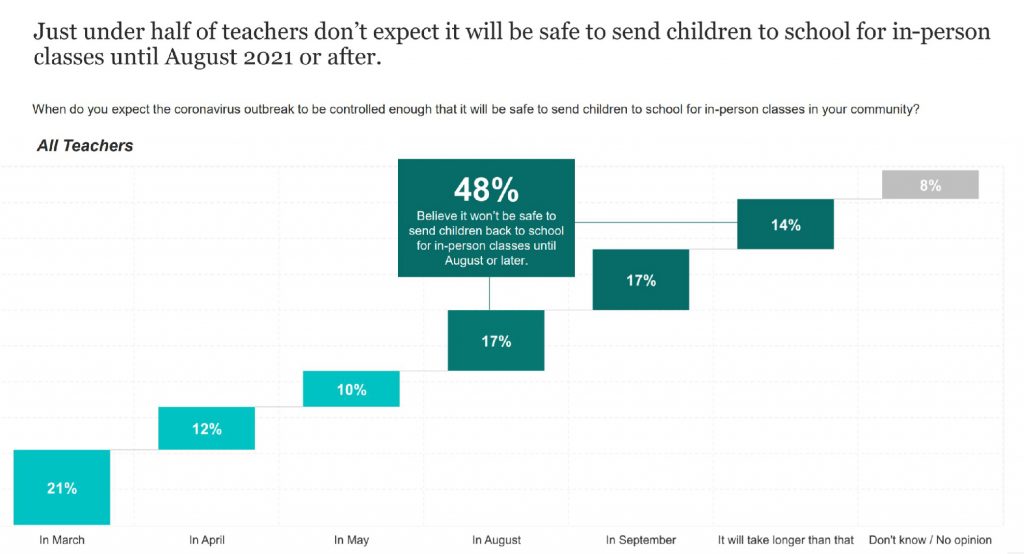

Teachers remain more positive than parents about current in-person education when asked when they think classrooms will be safe. For months, majorities of parents have indicated they think schools won’t be safe enough for in-person classes for at least four months. Likewise, in March, 55 percent of parents said in-person classes won’t be safe until the next academic year, compared to roughly one-third who think schools will be safe by May.

In comparison, nearly as many teachers think classrooms will be safe this school year as those who do not, at 43 percent and 48 percent, respectively.

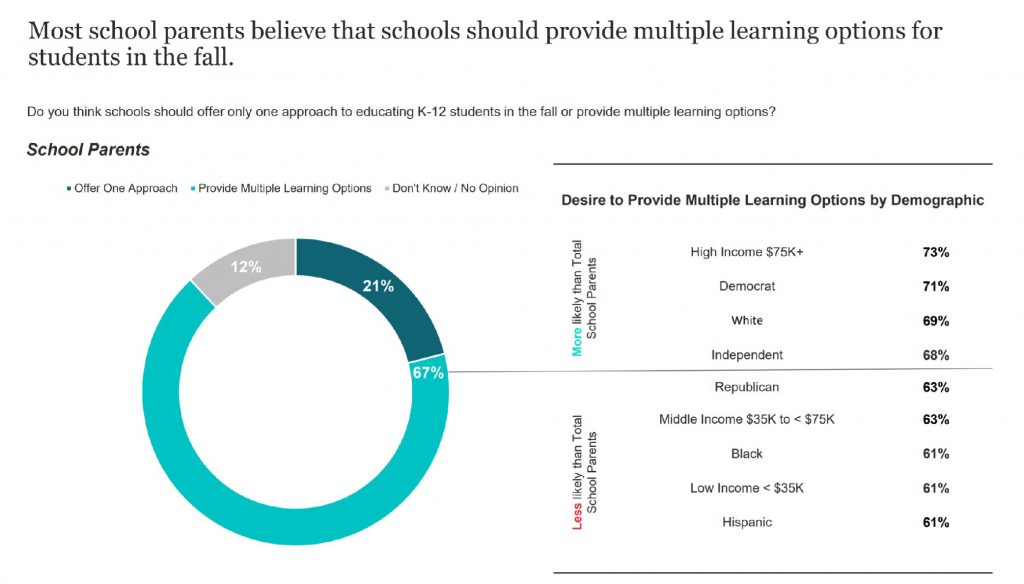

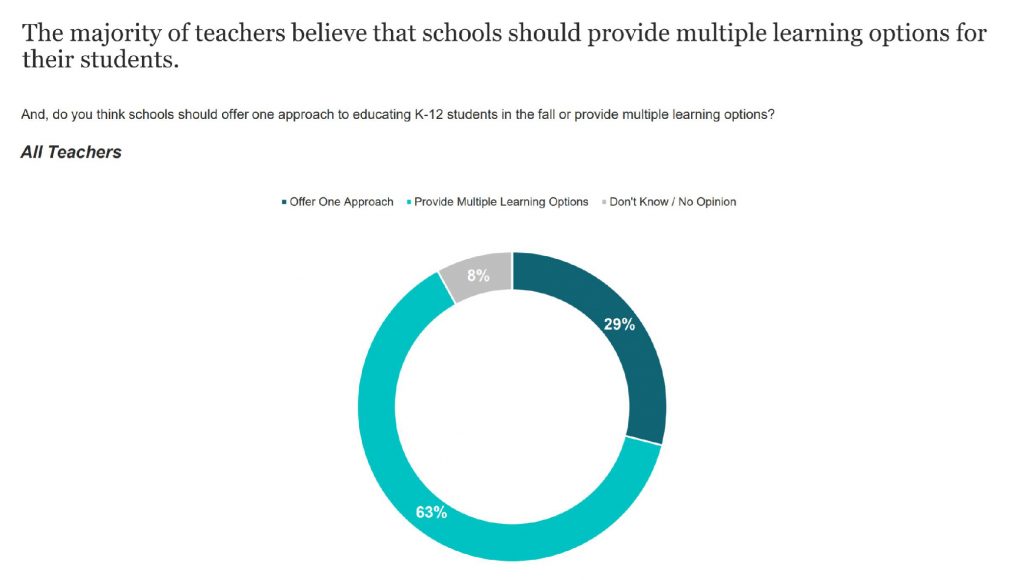

2. Both parents and teachers favor options in education formats. Two-thirds of parents and 63 percent of teachers think schools should offer multiple kinds of learning options for students next academic year. Parental preference for multiple options is positively correlated with income.

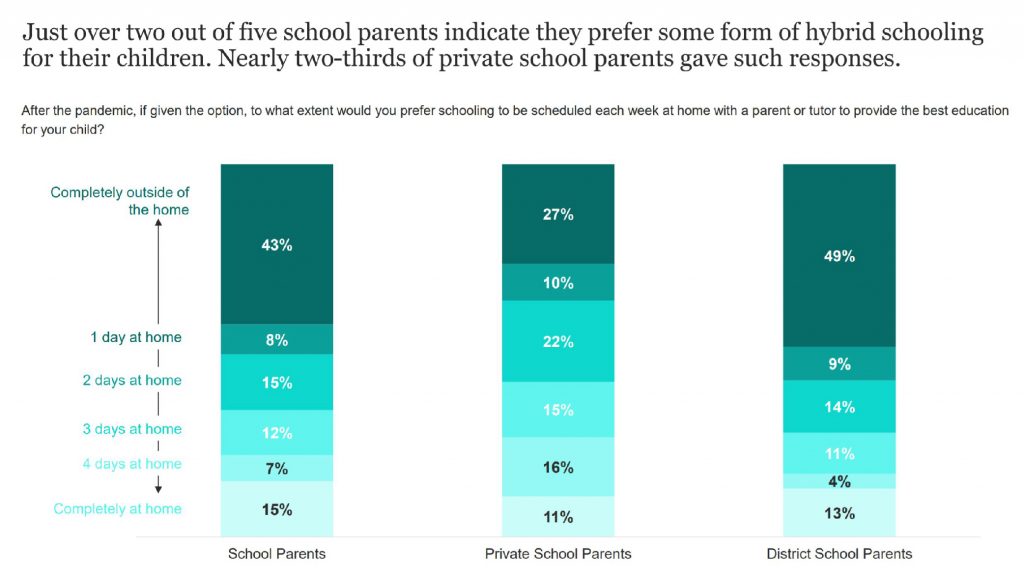

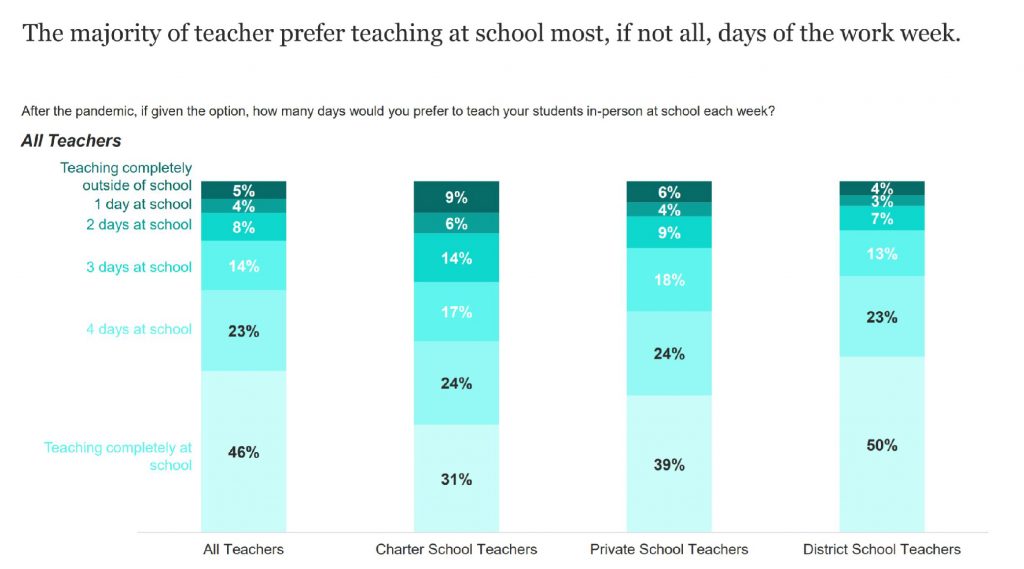

If given the option, both parents and teachers say they would utilize multiple formats in the long-term. 42 percent of parents and 39 percent of teachers say they would ideally go to school one to four days per week, conducting the rest of learning from other locations. Both district school parents and district school teachers are more likely to prefer an academic schedule based entirely in schools.

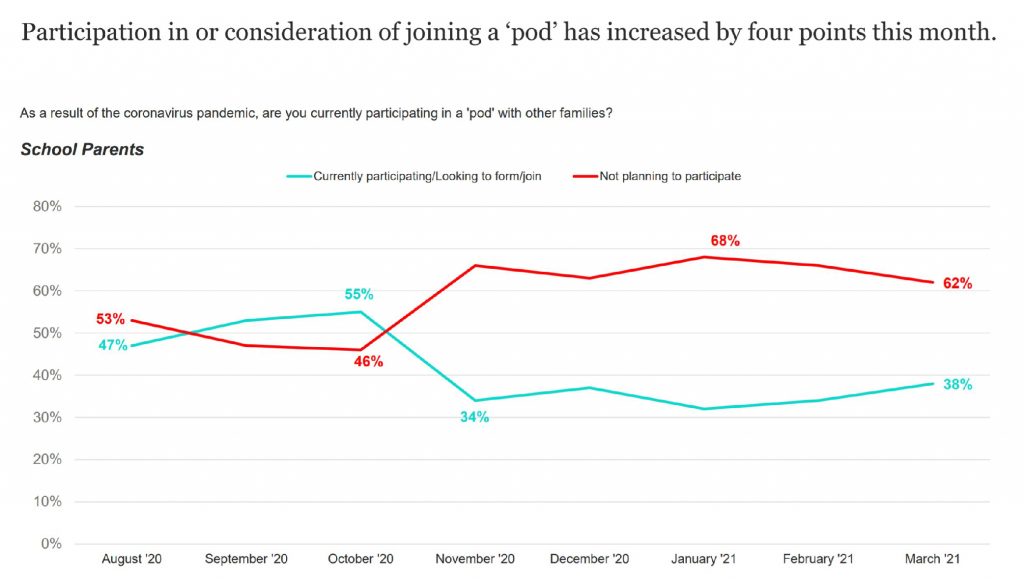

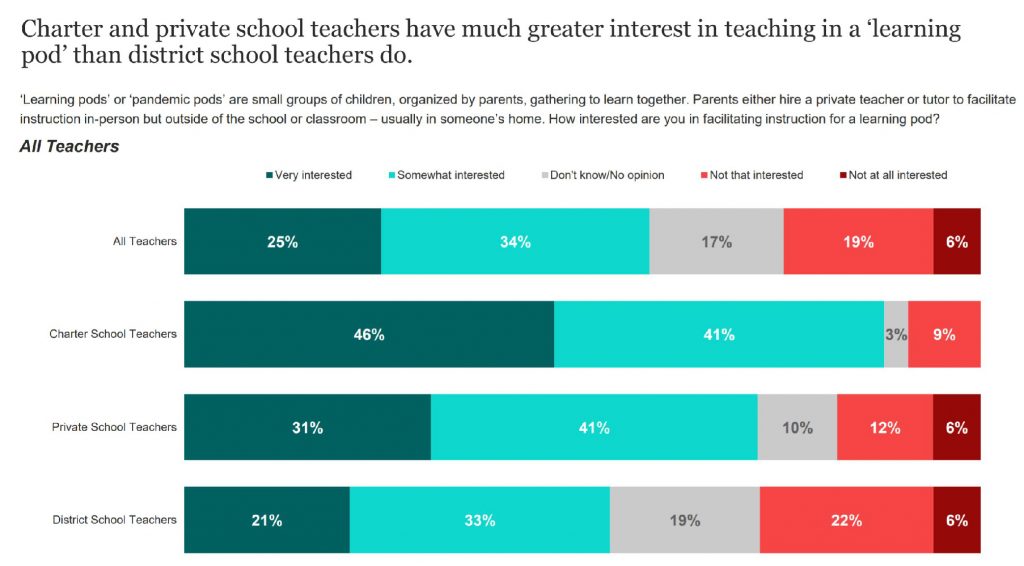

3. Teachers, especially those working at charter and private schools, are interested in working at “learning pods.” Learning pods, also known as “pandemic pods” or “microschools,” proliferated in the last year. Parents indicating their families were participating in or looking to join pods peaked in October 2020 at 55 percent. Since November, that number has hovered between 30 and 40 percent.

Many pods employ private teachers to facilitate instruction. We asked teachers if they would be interested in educating children in this format. A majority of them said they would be at least somewhat interested, and one out of four said they would be “very interested.” Charter school teachers are especially interested, with nearly half indicating strong interest. Private school teachers also are interested in pods significantly more than their district school counterparts.

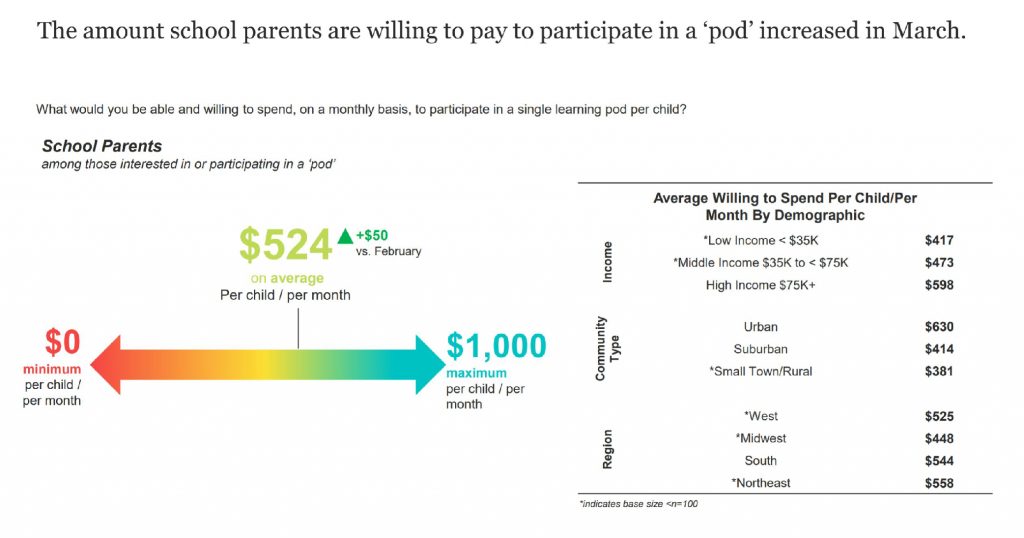

We also asked parents and teachers interested in pods to take finances into account. For parents, we asked how much money per child they would be willing to pay to participate in a pod. In March, the average parent said they would pay $524 per child per month to participate in a pod, about $100 more than the average response in January.

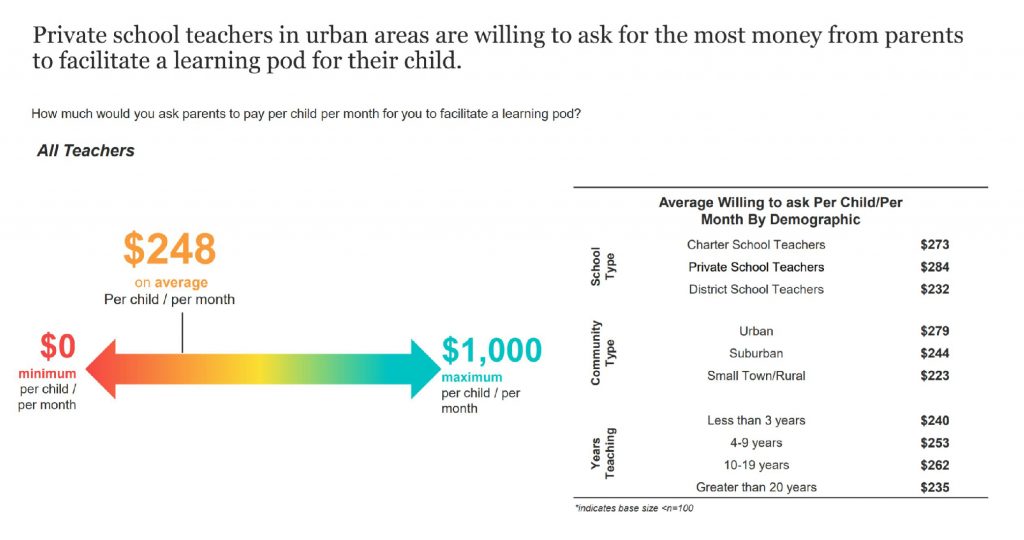

We asked teachers how much compensation would be required for them to teach in a pod. Their average asking price was less than half of parents’ average willingness to pay, at just $248 per child per month.

One limitation in interpreting these survey answers is that teachers were not given an indication of how many children they would be teaching in this hypothetical scenario. One teacher may expect to teach 15 children while another may expect a smaller pod of five students. All else equal, the compensation per child needed for teaching in a pod to be “worth it” would be different for these two teachers.

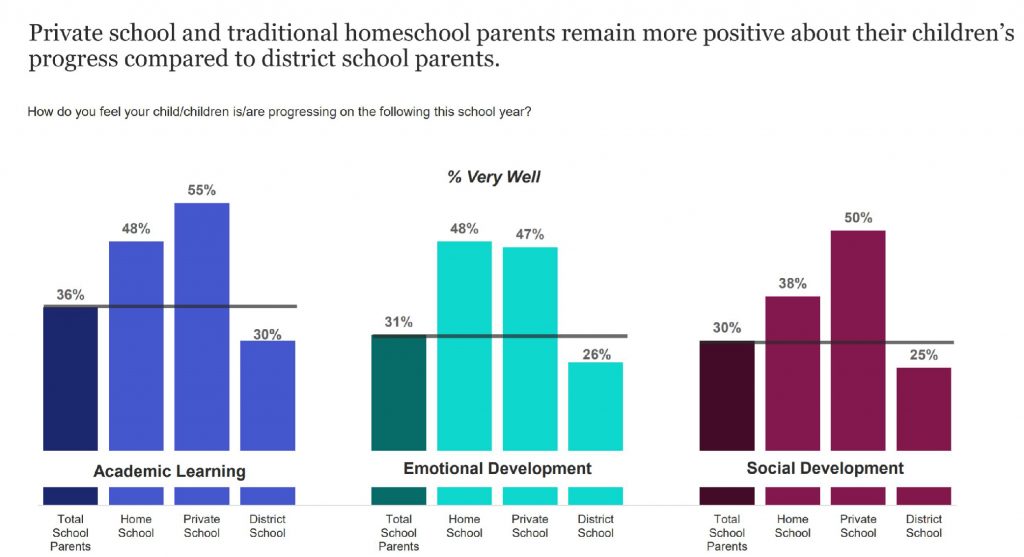

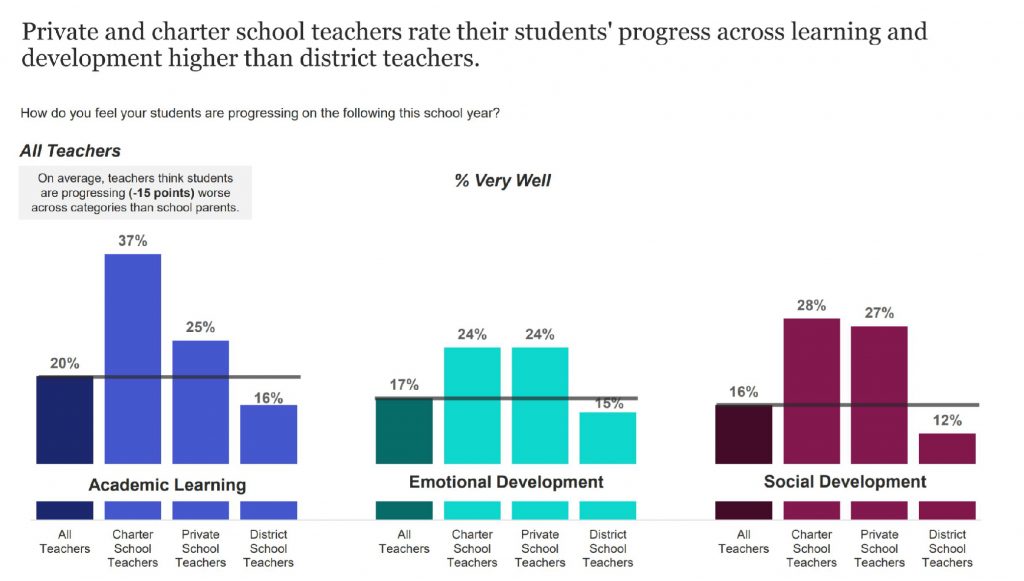

4. Parents are more optimistic about their children’s development this year than teachers are about their students. We’ve asked parents how they feel their children are progressing academically, emotionally, and socially this year. In March, the share of parents saying their children are progressing “very well” increased by 8 percentage points in academics, 6 percentage points for emotional development, and 3 percentage points for socialization relative to February. Over the course of this school year, private school parents have tended to display greater positivity about their children’s development than district, charter, or homeschooling parents, and that trend held true for academics and socialization in March. Homeschooling and private school parents are essentially equally positive about their children’s emotional development.

On average, teachers are 15 percentage points less likely to consider their students progressing “very well” than parents. Just one-fifth of teachers believe their students are progressing very well academically, and 17 and 16 percent of them are very positive about their students emotionally and socially, respectively. Notably, while private school parents have been the most positive parents by school type, charter school teachers are significantly more optimistic than private school teachers about their students’ academic progression this year.

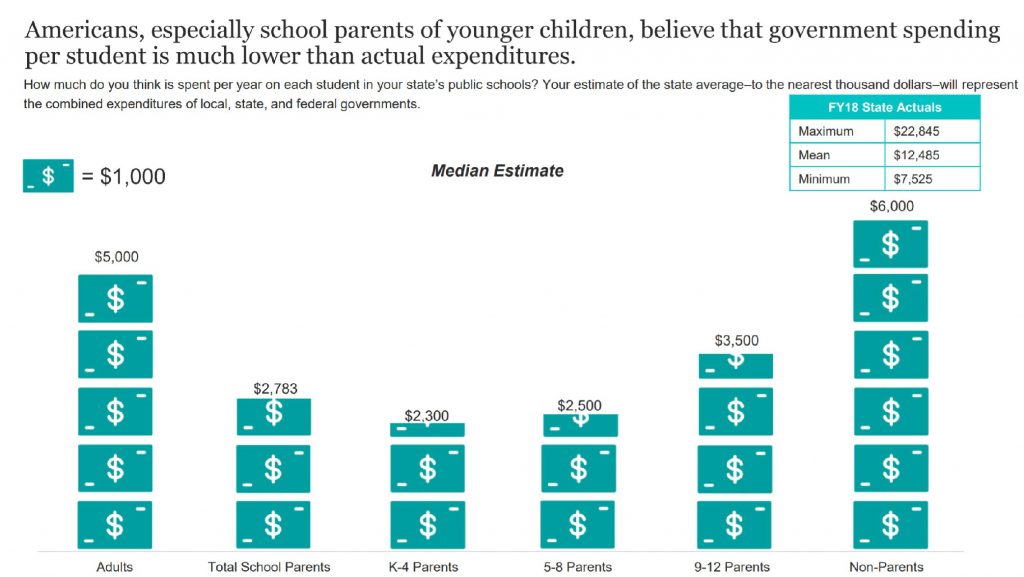

5. Teachers more severely underestimate public spending on K-12 education than the general public. For a few months, we have asked Americans how much money per student they think governments give public schools. Consistently, the median estimate among all adults is $5,000. School parents think the number is half that, with the median estimate being $2,783. Both of these guesses are severely below actual government spending. The average per-student public school spending in the U.S. is $12,485. Even the state with the lowest per-student spending still spends nearly three times what parents expect, at $7,525.

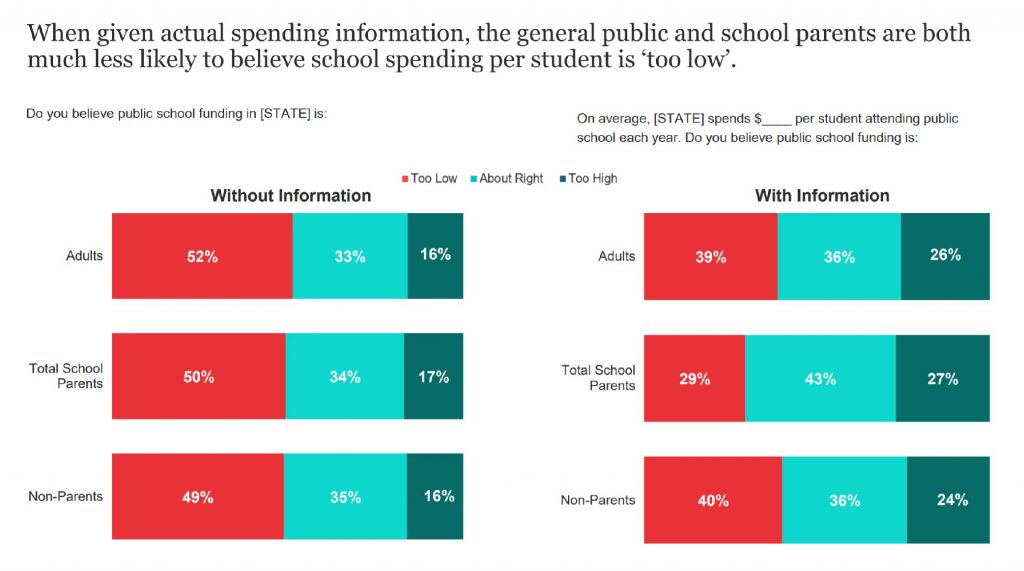

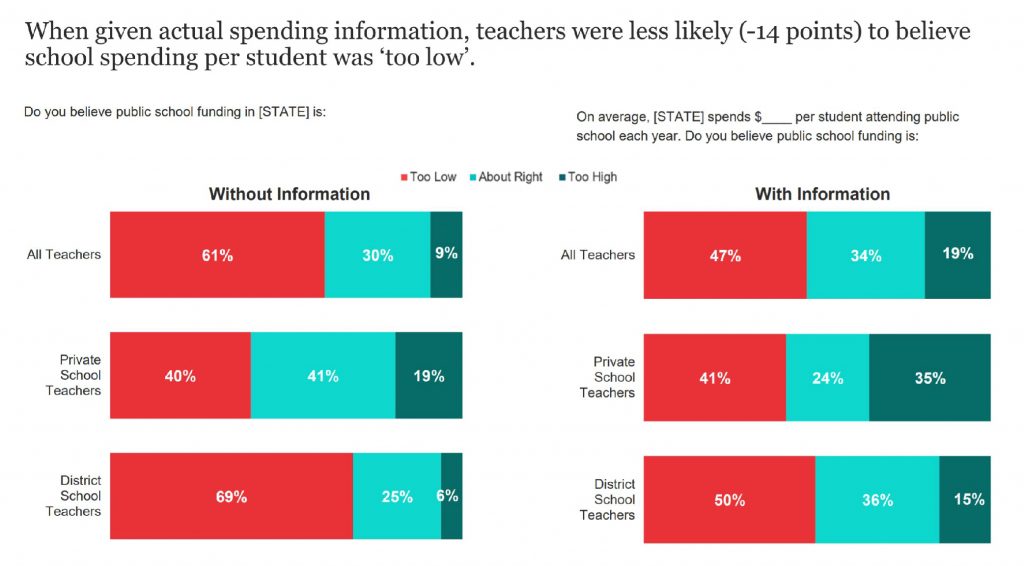

Learning what actual per-students spending is has a tangible effect on people’s opinions about school spending levels. In a split-sample poll, respondents who learn how much their state spends on public schools are substantially less likely to say public school spending is “too low” than those who do not—especially if they are school parents.

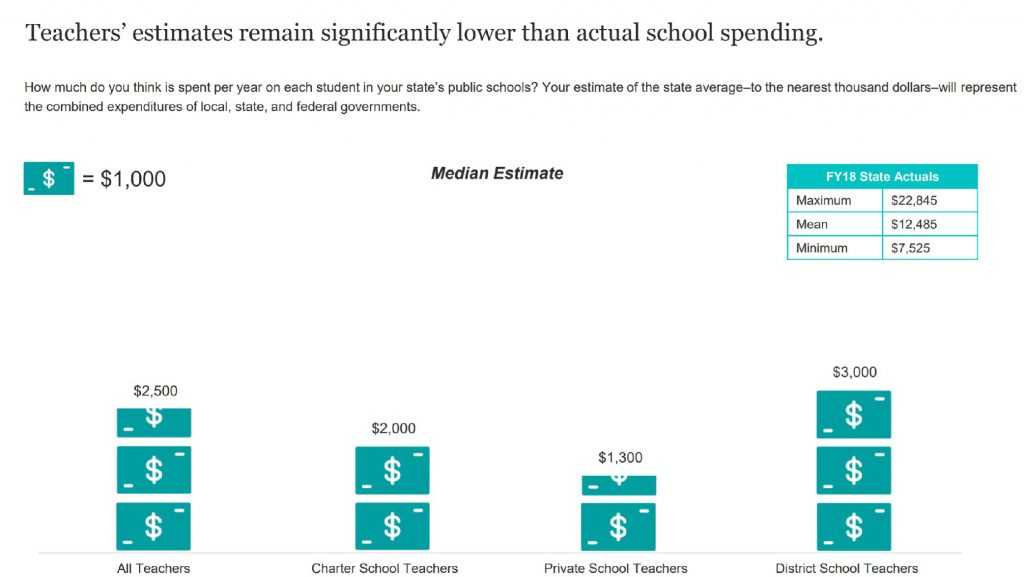

This trend is even starker for teachers. District school teachers have higher public school spending estimates than charter or private school teachers. At $3,000 per student, however, this estimate remains well less than a quarter of the national average.

In another split-sample question, district school teachers also were substantially less likely to say public school spending is “too low” if they learn what actual public spending on K-12 education is in their state. In fact, at a 19-point drop, the swing was greater than that of parents and adults more broadly. Still, a broad conclusion is that teachers are more likely to say public school spending is too low, including private school teachers.

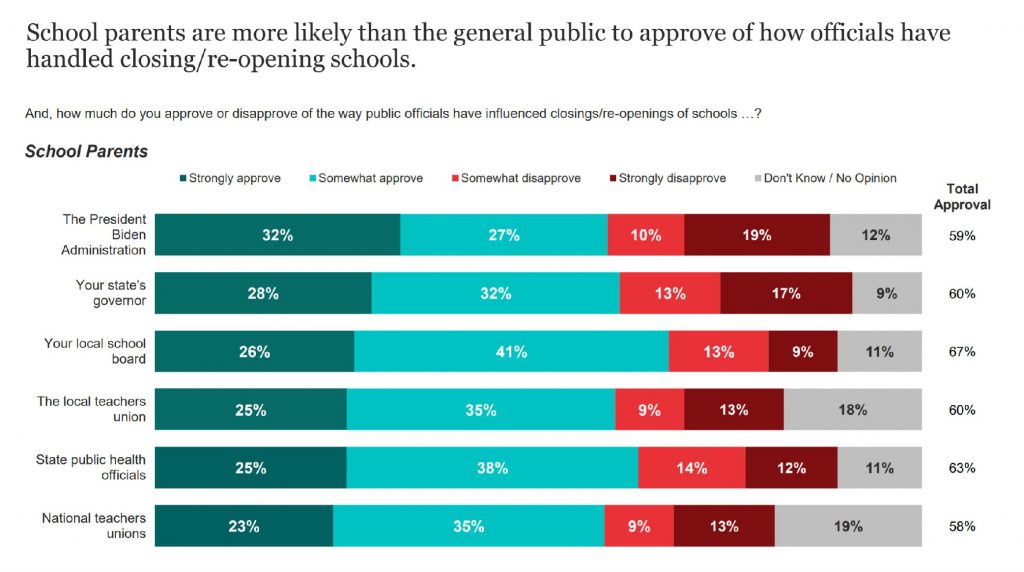

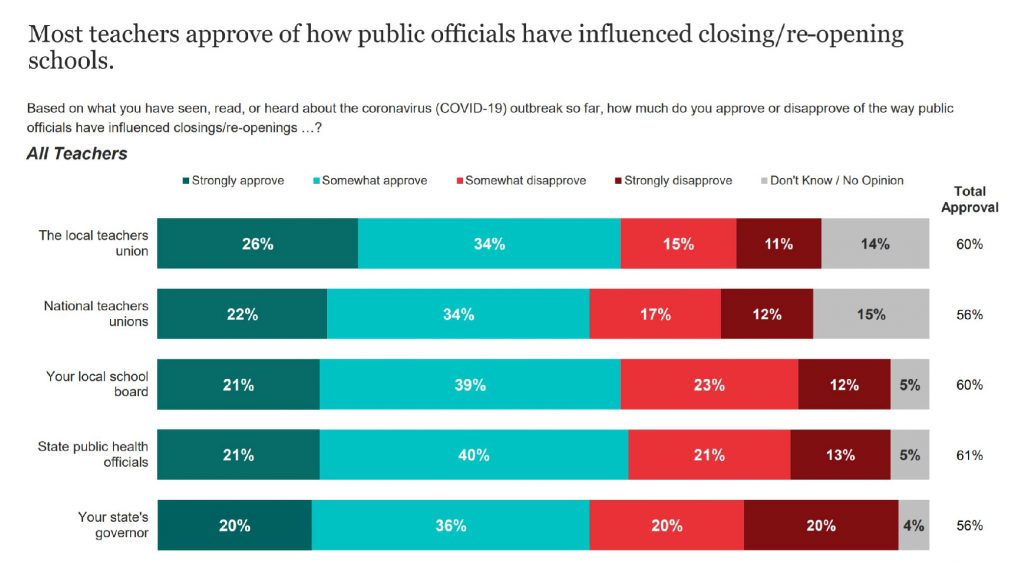

6. Teachers approve of unions’ influence on school reopenings to about the same degree as parents. Three-fifths of parents and three-fifths of teachers at least somewhat approve of their local teachers union’s role in their school’s closing and reopening policies in the wake of COVID-19. Strong approval also is essentially equal, at 25 percent of parents and 26 percent of teachers. National teachers unions have slightly lower approval ratings regarding reopening policies than local unions. Unlike parents, however, teachers rate both local and national teachers unions higher than all other public institutions presented.

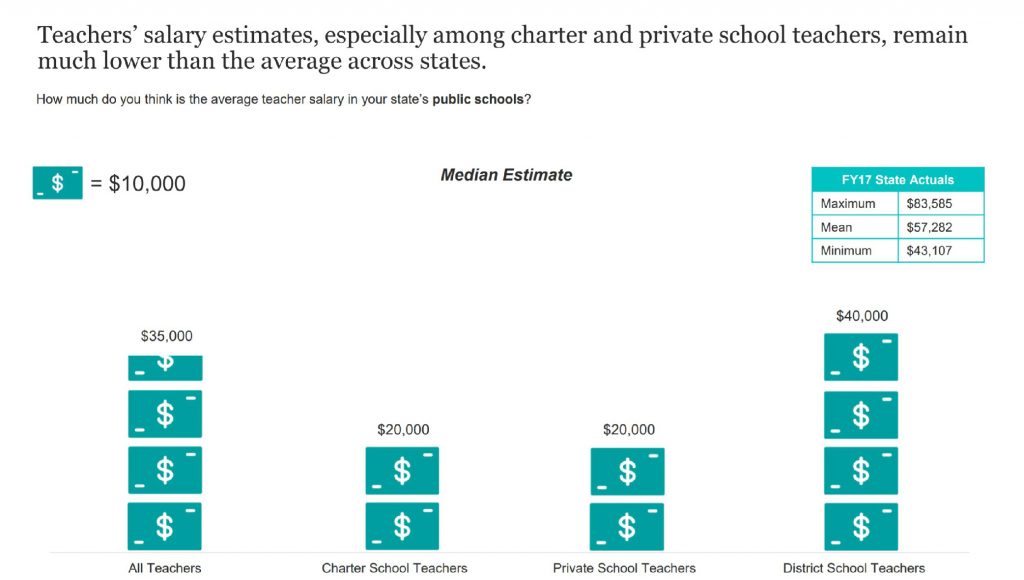

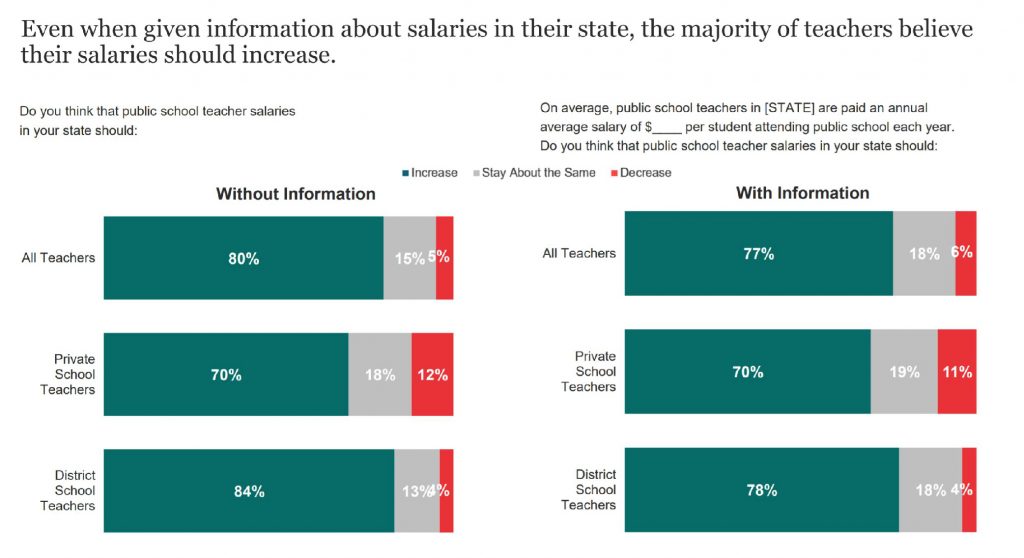

7. Teachers underestimate how much teachers are paid. We asked teachers how much they think the average teacher makes in their state’s public schools. As with overall K-12 spending, district school teachers have a higher estimate than charter or private school teachers, who estimate remarkably low average salaries of $20,000 per year. At $40,000, the median district school teacher estimate is still lower than the national average salary, and it is also below the average of the lowest-paying state in the country.

Significantly underestimating average teacher salaries did not significantly impact teachers’ belief that teacher pay should increase.

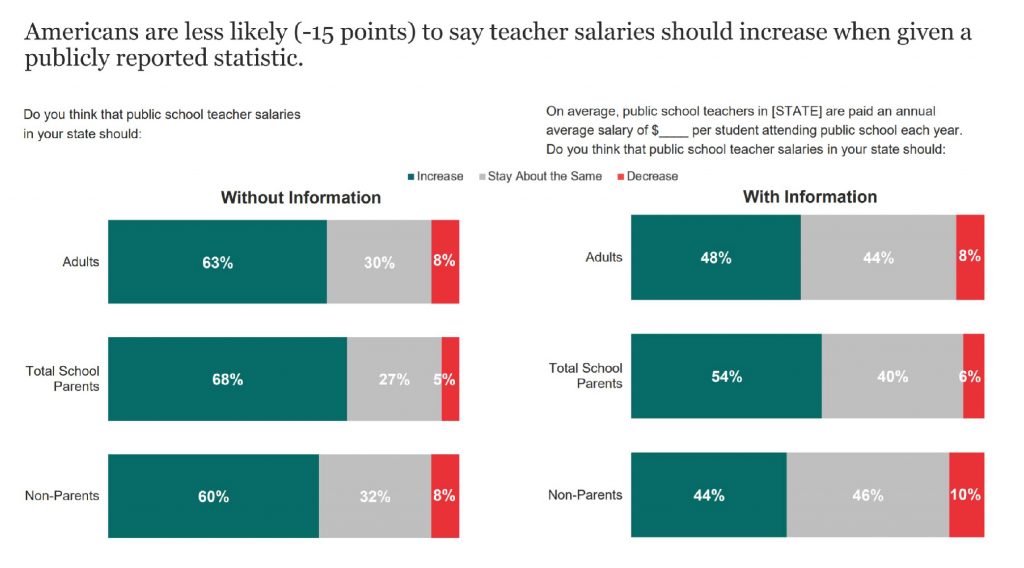

Americans also underestimate teacher pay to about the same degree as district school teachers. Unlike teachers, however, those that learn what the average teacher salary in their state actually is are noticeably less likely to believe teacher salaries should increase.

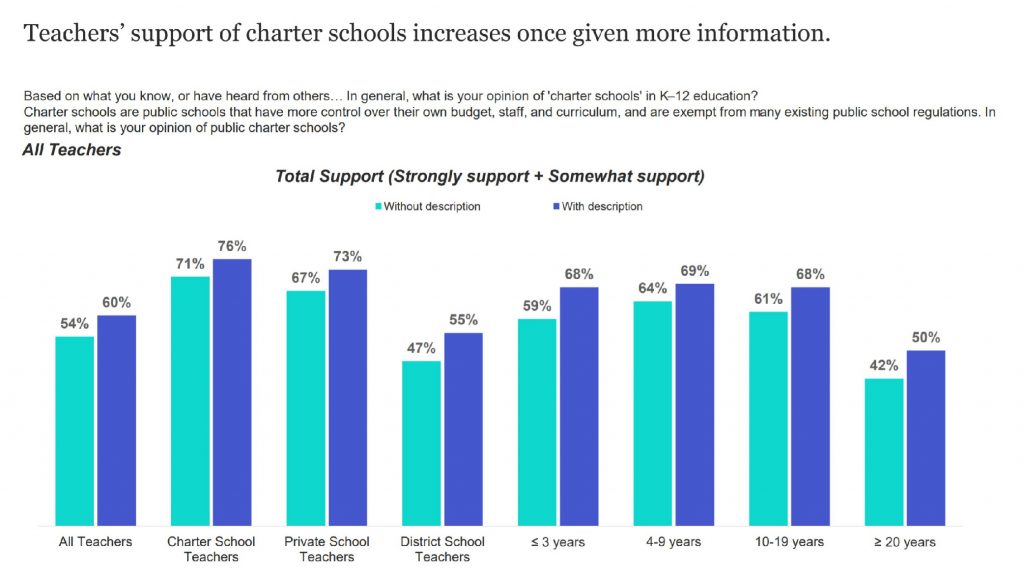

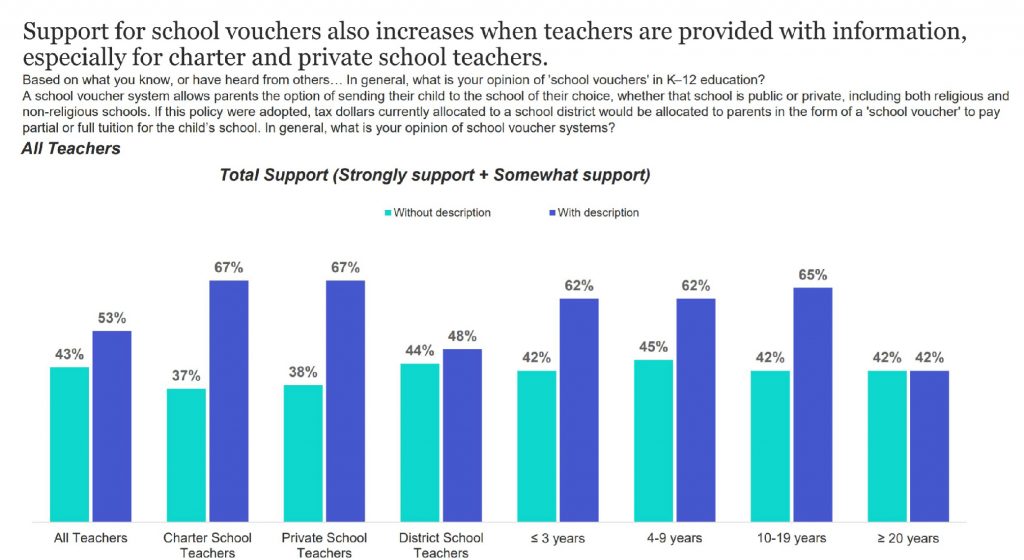

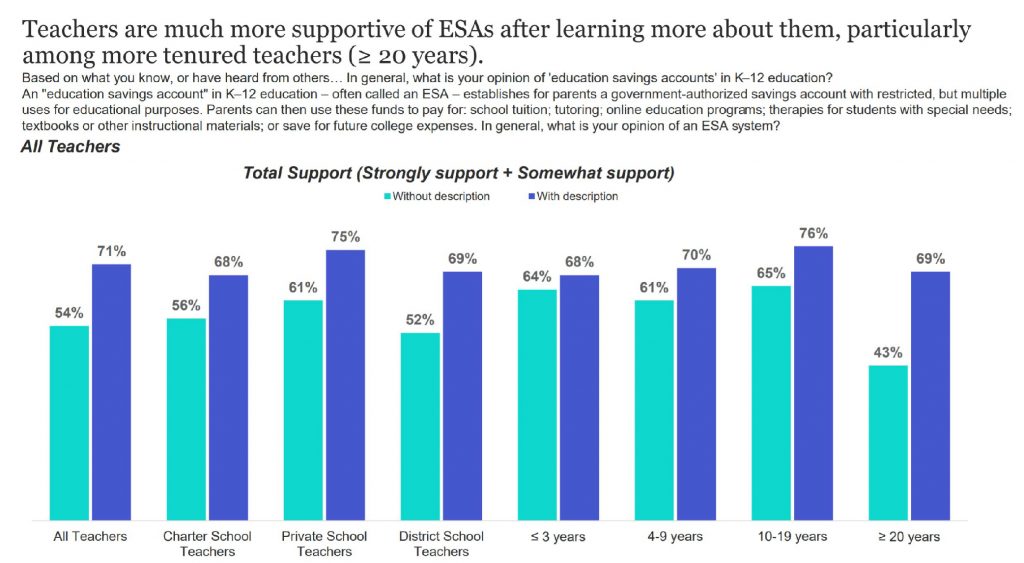

8. A majority of teachers support school choice policies. While lower than that of school parents, most teachers at least somewhat support charter schools and education savings accounts (ESAs), and a majority also support private school vouchers once given a description. While district school teachers, perhaps unsurprisingly, are less supportive of school choice policies than charter or private school teachers, a majority of them still support ESAs, a majority supports charters when offered a definition, and 48 percent support private school vouchers when defined.