Public Schools Should Rise Above [Which] Mark?

A new education documentary provides another glaring example of how the lack of consumer choice in K-12 education undermines the efficient allocation of resources to our schools. Unfortunately, the way the film portrays the recent squeeze on public school finances leaves out a lot of important context.

Produced by Indiana’s West Lafayette Community School Corporation, home of Purdue University, Rise Above the Mark pushes back against forces its creators feel are unfairly attacking public schools. West Lafayette’s public schools are widely regarded as among the best, if not the very best, in Indiana. The film centers primarily on how changes in accountability requirements have taken much of the joy out of teaching and have interfered with teachers’ ability to help the students that really need it.

Although there is some truth to that, a key segment of the film, dedicated to the financial squeeze public schools have been facing, deserves greater scrutiny.

Through the last half of the 20th Century, spending on public schools outpaced the growth of the economy and most other state and local government spending. A pace that was simply not sustainable.

No question, when Mitch Daniels was elected Indiana governor in 2004, downward pressure was put on state spending as he worked to simultaneously reverse the budget deficit he inherited and address an ongoing property tax revolt across the state. Then, just as he was being re-elected, the Great Recession of 2008 hit bringing more financial pressure and pain to a wide swath of the U.S. economy. An impact from which, six years later, many sectors have still not yet fully recovered. Among those still staggering back to their feet are state and local governments. All of those factors have had a direct effect on Indiana’s public schools over the past decade as the vast majority of their funding comes from state and local taxes.

As the former Controller for the City of Indianapolis, during this downturn, I can attest to these financial challenges firsthand. I know most school business officials have had a rough go of it in recent years.

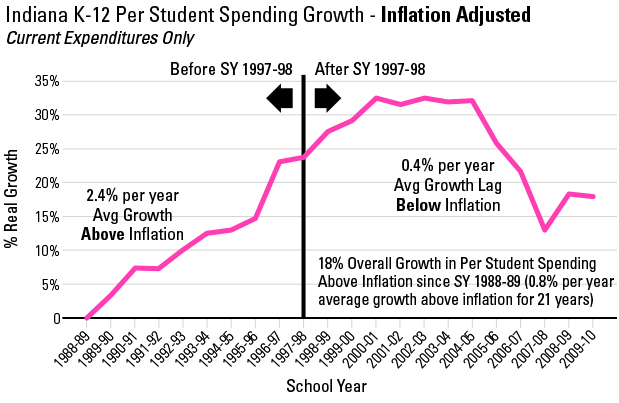

Emphasizing school spending since 1998, adjusted for inflation, the film claims that financial pressure and inflation have eroded school resources. For example, it cites an analysis showing funding available for a typical classroom, costing $100,000 to operate in 1998, drop to only the equivalent $82,500 in 2012. That’s a 17.5 percent decline over 14 years! It also cites 2002 as the high water mark for public school funding, with inflation-adjusted per-classroom funding at the equivalent of $107,850, meaning the drop over just the last 10 years has been even sharper. Presumably, the 2002 level is “the mark” which the filmmakers are suggesting we must rise above (though not stated explicitly).

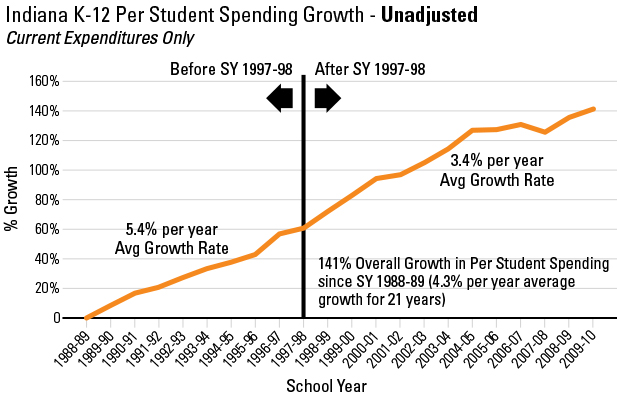

But such financial data, presented out of context, leads more often to confusion than to enlightenment. In this case, a little context reveals that unadjusted per-student spending by Indiana’s public schools, for “current expenditures” since 1998, rose by 50 percent through 2010. That’s an average annual growth rate of 3.4 percent, despite Gov. Daniels’ spending restraint and the Great Recession. In fact, spending per student (as measured by current expenditures) rose by 141 percent over the 21 years following the 1988-89 school year—a 4.3 percent average annual growth rate.

To be fair, over this same period since 1998, price inflation for state and local governments (as measured by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis) was 57 percent. So, it is true that public school nominal spending growth of 50 percent did slightly lag inflation. But the real financial challenge, during this period, was that inflation-adjusted school spending per student fluctuated greatly—rising sharply from 1998 through 2002, then falling sharply after 2005 (see figure below). No wonder public school officials have felt squeezed!

For the first time in decades, public school officials have had to deal with real funding constraints. That’s the point! Through the last half of the 20th Century, spending on public schools outpaced the growth of the economy and most other state and local government spending. A pace that was simply not sustainable. The October 2012 Friedman Foundation report, The School Staffing Surge: Decades of Employment Growth in America’s Public Schools, succinctly illustrates that fact.

So which mark are we supposed to rise above? Is surpassing the 2002 level of inflation-adjusted per-student spending the goal? Or should that 2002 level be viewed as an outlier—the high point of a cyclical upswing?

The filmmakers blame politics, and “out-of-touch” politicians, for all the recent problems in public education. They may have a point. It is impossible for a political system to allocate resources efficiently. Just as the recent squeeze on funding for public schools was effected by politicians, though triggered by other fiscal pressures, the earlier decades of rapidly rising public school funding was also a political outcome. Emotion drives the allocation of resources within a political system more so than across the broader economy.

The recent financial challenges of Indiana public schools, as cited in Rise Above the Mark, is another cautionary tale of the risk of ceding all power over the allocation of education funding to the political system. Introducing more consumer choice into the education marketplace will provide important signals about how much money is necessary to deliver a high-quality education to all students and where those dollars are most effectively applied.

Under a system of broad-based school choice, funding for schools (both public and private) will be determined more by the performance and true needs of schools than by the vagaries of a political process responding to partisan electoral pressures.