Should Anyone Use Student Test Score Studies to Determine School Choice Success or Failure?

Collin Hitt of Southern Illinois School of Medicine, Patrick Wolf of the University of Arkansas and I have a new working paper out with the American Enterprise Institute that challenges some fundamental assumptions about how we evaluate school choice programs.

One of the advantages research on school choice programs has is that we have data that follows students for a long time. Not only can we measure short-term changes in student tests scores, but we can also look at later life outcomes like high school graduation and college matriculation.

One would assume that programs that improve test scores would also improve later life outcomes. Digging into that research, though, it appears that improving test scores is neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for increasing graduation, college attendance or college graduation rates.

How do we know this?

Well, my coauthors and I collected every study we could find that studied some kind of school choice program (everything from school vouchers to charter schools to career and technical education schools to early college high schools to small schools of choice) and provided results on both short-run test scores and long-run educational attainment results. We then used simple vote-counting methods to classify whether or not the findings for each were positive or negative and whether they were statistically significantly so.

What we found were multiple instances where the studies’ findings did not line up.

In some cases, studies that had shown negative test scores in the short run showed positive graduation rates in the long run. In others, short-term test score gains did not translate to positive long-term results.

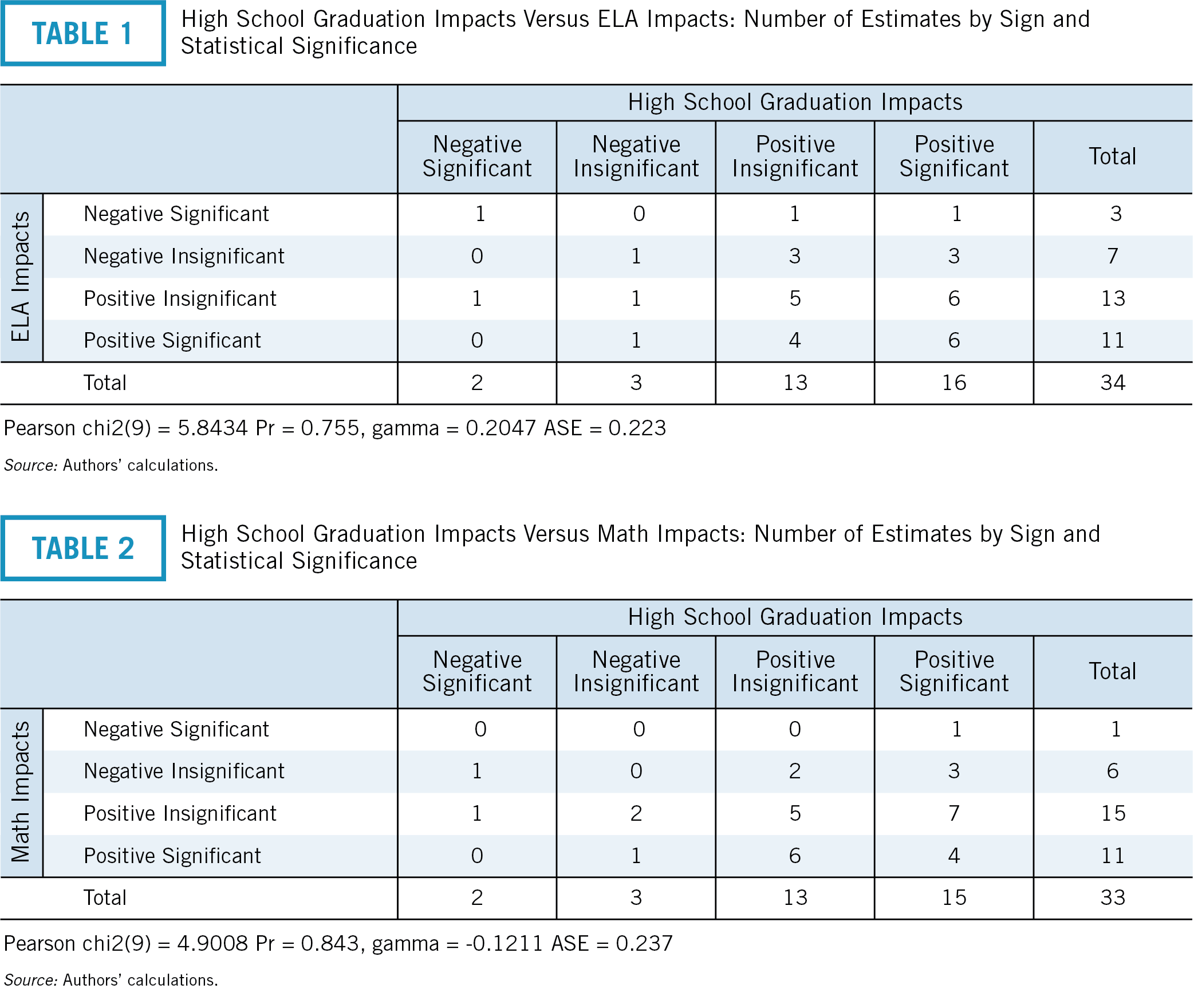

Here is the first table from the paper, where we have a visual representation of the findings for each study that looked at test scores and high school graduation rates. In theory, if the achievement and attainment results were the same, all of the findings would appear in a line starting in the upper left corner and ending in the lower right. Studies that found significantly negative achievement findings would also find significantly negative attainment findings, etc. etc.

As you can see, they do not. Of the 34 total findings for English Language Arts, only 13 match up. Of the 33 total findings for Math, only nine match up. The rest are spread out across the board.

I’ll spare you the rest of the tables. If you want all of the gory details, you can find the paper here.

But what does all of this mean for policy? In our conclusion, we write:

“The most obvious implication is that policymakers need to be much more humble in what they believe that test scores tell them about the performance of schools of choice. Test scores are not giving us the whole picture. Insofar as test scores are used to make determinations in “portfolio” governance structures or are used to close (or expand) schools, policymakers might be making errors. This is not to say that test scores should be wholly discarded. Rather, test scores should be put in context and should not automatically occupy a privileged place over parental demand and satisfaction as short-term measures of school choice success or failure.”

This is a working paper, so we’re always open to feedback. As more and more studies of various school choice programs are conducted, we should be able to add to the sample and see if the pattern holds up.