Could We Solve Poverty and Pollution with School Choice?

It may seem obvious—people want to live near the best schools. But have you ever thought about the problems created when families flee weak school districts?

Recently, while visiting Atlanta, I came face-to-face with a disheartening reality: the sight of neighborhoods in deep poverty sitting in the shadows of gleaming skyscrapers.

These mammoth buildings contain relatively wealthy workers who pack the interstate twice a day for their commutes from the suburbs, making Atlanta traffic rank as some of the worst in the world. Recognizing the stark contrast of those working in downtown vs. those living near downtown, I was sad to see that even in Atlanta, a place considered a success story, there are many poor people trapped in geographically concentrated poverty. Why is this happening in cities across the US?

In this post, I will discuss how school assignments have helped create pockets of poverty by promoting a phenomenon known as spatial sorting. Then, I will describe a few potential solutions—solutions that address a major social justice issue and perhaps the biggest environmental issue in our country today.

SCHOOL ASSIGNMENTS AND SPATIAL SORTING

How It Works

So, what is spatial sorting? This term refers to a phenomenon where people are geographically separated when:

- politicians draw school boundary lines

- families who can afford to choose to live on the side of the line with better schools (‘voting with their feet’)

- the quality of life—schools, family income levels, poverty rates, crime rates—on either side of the line become drastically different.

One side of the line becomes economically healthier and the other side more economically depressed. Those who can’t afford to live “on the good side of the line” are left behind geographically, but also economically and socially. This destructive process of economic segregation also moves job opportunities away from poor areas and to where wealthier families cluster.

The effects of spatial sorting are even clearer when comparing the number of school-aged children in cities to their suburbs. Across America the number of children in age groups 0–4 and 5–9 is equal. So, keeping this figure in mind, census data shows the drastic exodus of middle class families to the suburbs when children hit age 5.

Atlanta, for example has 15 percent fewer 5- to 9-year-olds than 0- to 4-year-olds. Where have school-aged children gone? Across district lines and into the suburbs.

Traffic between Atlanta and its suburbs can be horrendous because parents spend hours commuting to a city that they will not let their children live in. It’s an environmental and sociological disaster.

COLOR OUTSIDE THE LINES

Examples and Ideas

And now for good news! There are places and systems that ignore the lines drawn by politicians and that undermine spatial sorting.

And now for good news! There are places and systems that ignore the lines drawn by politicians and that undermine spatial sorting.

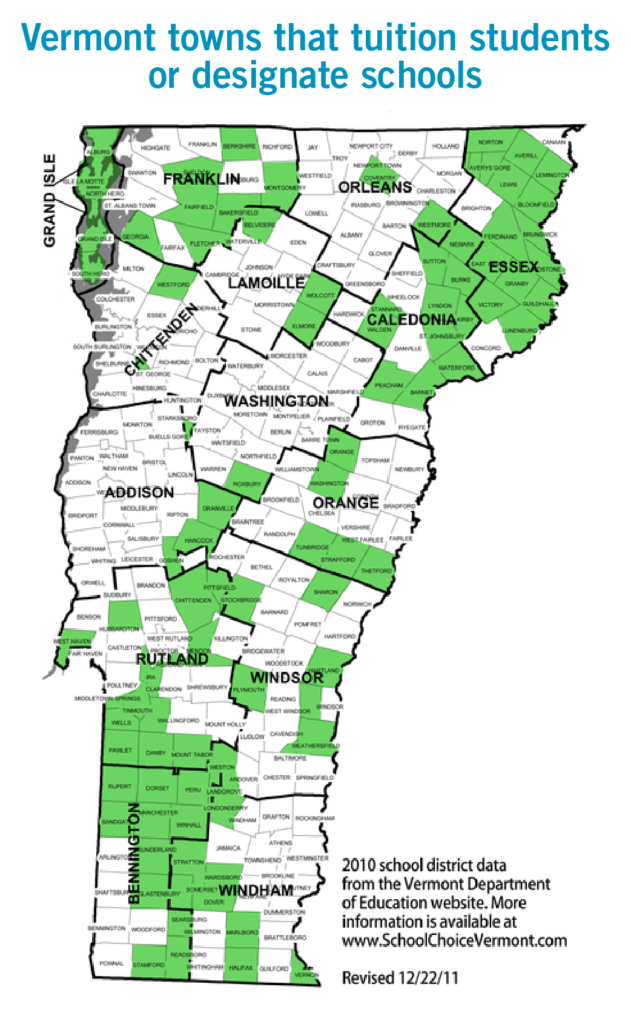

One interesting example, the “tuitioning system” in Vermont, has been around since the 1800s. In Vermont, towns that do not have their own public schools pay for children to attend private schools or public schools in nearby towns. Some children even attend out-of-state schools. Some have gone to school in Canada!

In 1998, the Winhall school district in Vermont moved from the assigned-school model to the tuitioning model, offering an interesting case study on tuitioning. Winhall had a poor-performing public school, so the district switched to tuitioning and gave the old school building to a new private school that agreed to take all students in the district (if they desired to attend).

What happened?

Spending per child went down, test scores went up and families with children were and are now inclined to stay in the district. Census data show 14 percent more school-aged children live in this area than pre-schoolers do, meaning families with school-aged children are moving into the district. In other words, the Winhall school district points to the potential for combatting the mass exodus of families with tuitioning.

Research also shows that Vermont’s tuitioning districts have higher property values too, a sign that having choices is economically valuable. This Vermont newspaper article also clearly captures the switch to tuitioning as the impetus for a local real estate boom.

Vermont is not the only place that allows families to “color outside district lines.” Many charter schools operate without attendance zones.

As previously published by EdChoice, the Orange County School of the Arts (OCSA) exemplifies the family relocation impact a good school can have on an urban area. In this case, this charter school relocated to Santa Ana, a distressed area that has had one of the worst 5- to 9-year-old departure rates in Southern California. After the school relocated to the city, hundreds of families moved to get closer to the school, with many moving into the city. Crime rates around the school declined significantly. And OCSA’s story is one of many accounts where charter schools have changed the face of struggling communities.

DON’T COERCE

Do the Reverse

So, what can cities learn about using schools to combat poverty?

First, it is important to recognize that drawing lines around schools and assigning children to them can begin a chain of events causing urban schools to decline, ultimately causing economic segregation and blight.

Second, cities should adopt systems that allow families to ignore lines, such as Vermont’s tuitioning, which has offered a successful example for 150 years.

Spatial sorting is obviously disastrous for poor communities. But spatial sorting is a problem for the middle class as well—creating sprawl, long and expensive commutes, traffic congestion and increased CO2 emissions, not to mention raising the incidence of diseases like diabetes and high blood pressure that could be avoided without long, sedentary commutes.

WE’VE GOT THE POWER

Spread the word

Until recently, city school boards had exclusive control over school policy, keeping conversations about neighborhood impact off the table. Other public officials charged with fixing neighborhoods couldn’t do anything about schools, even though schools are the most powerful economic development lever available.

But now, these new conversations are shifting the imbalance of power, making mayors and city councils (who are bold enough) willing to grab this lever. YOU have power too. If you feel passionate about the future of our neighborhoods, share this post with your mayor, councilmen, councilwomen or county commissioners.

But maybe you’re not convinced that school choice can create economic development. Got questions? Tomorrow we’re tackling the question, “How can scholars have all the same facts about school choice and the economy but arrive at different conclusions?” Want the answer? Stay tuned for our next post.

Read the second post in this series: Why Do Experts Disagree on How to Approach Concentrated Poverty and Education?