Studying the Pursuit of Innovation: How Does Competition Affect K–12 Education?

It’s time to stop treating the problem of educational productivity as a grinding, eat-your-broccoli exercise. It’s time to start treating it as an opportunity for innovation and accelerating progress.

– Former U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan, November 17, 2010

States have been charged with doing more with less in recent years, a state of affairs termed “the new normal” by Duncan back in 2010. But productivity in any sector is never achieved by chastising or cajoling. Advances in the efficient delivery of a high-quality service are most likely to occur in response to strong incentives. Competition for student enrollment provides exactly this type of pressure on schools.

In a 1983 edition of Newsweek, Milton Friedman proposed, “The only solution is to break the monopoly, introduce competition, and give the customers alternatives.”

Our new report for the Friedman Foundation, Pursuing Innovation, takes a deep dive into that proposal by documenting how much and what types of competition currently exist in K–12 education, predicting which forms of competition are most likely to generate pressures for improvement in K–12 education, and brainstorming policy attributes that will maximize the effectiveness of competition-based education reforms.

The Types of Competition That Exist in K–12 Education Today

A small amount of competition in education already exists, but the types of students who stand to benefit the most are shielded from the transformative potential of competition by public school monopolies.

For instance, data from the U.S. Department of Education’s National Household Education Surveys Program reveal that parents who are the least likely to say they moved to their current neighborhood specifically to gain access to the local schools are typically black, poor, have lower levels of educational attainment, or live outside of an urban area. Basically, both resources (income and education) and opportunity (urban location) influence a family’s willingness and ability to exercise residential school choice.

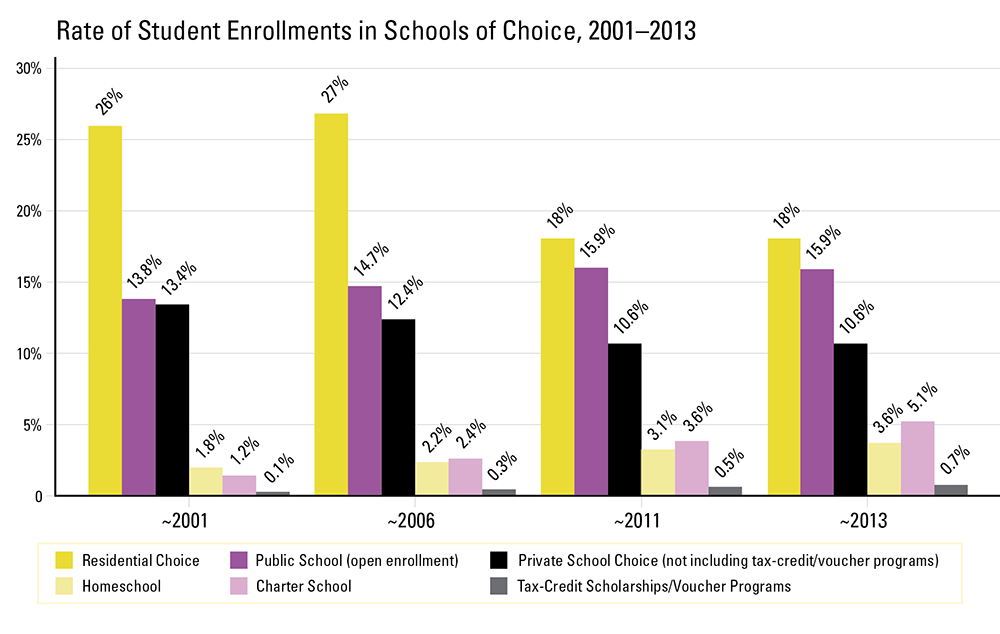

What’s changed in recent years, however, is the number of formal school choice programs designed to extend options to families with limited financial means.

By the spring of 2015, a total of 43 school voucher, tax-credit scholarship, and ESA programs enrolled more than 350,000 students, which is still a small percentage of all K–12 enrollments (about 0.7 percent), but a considerable increase from 2001 when six programs enrolled a mere 31,000 students.

The Styles of Competition Most Likely to Generate Improvement

As targeted school choice programs continue to expand, so does the number of students who can signal dissatisfaction with outdated or ineffective teaching and learning strategies by choosing to attend a different school.

We describe the most common types of school choice programs that state policymakers have implemented. Not all of these alternatives are authentic competitors to traditional assigned public school districts, however. We identify four reasons why charter schools and taxpayer-funded private school choice programs deserve close consideration as possible sources of authentic competition with local public school districts:

- Money leaves the district school when a student transfers out

- Many states are starting to shed enrollment restrictions on such programs (e.g., charter school caps)

- Student enrollments continue to grow at an aggressive rate

- Such programs are designed for students who would likely otherwise attend district schools

Because they don’t share these four features, other forms of school choice—such as inter- and intra-district choice, family-financed private schooling, residential school choice, and homeschooling—are less likely to invite a strong competitive response.

In spite of the sincere efforts that have been made to date to spur innovation in teaching and learning in the traditional public school sector, the data show that just infusing more per-pupil public school spending in the past has failed to propel the U.S. beyond its peer countries on international rankings of student achievement.

In fact, education productivity back in 1970–71—defined as NAEP points per thousand dollars of per-pupil spending—was between 80 and 110 percent higher than productivity today. Rather than focusing on simply raising the level of funding made available for education (and the tradeoff of other public priorities required by such an approach), we should view our productivity failure as a signal that we need to alter education’s incentive structure.

The Policy Features That Will Maximize Effectiveness

Education policy can be designed to maximize the potential benefits of competition-based education reforms, or not.

When drafting the legislation and rules that will govern implementation of an education policy, policymakers should consider design decisions that will encourage innovative and thematically diverse schools and educational offerings. Take, for instance, Louisiana’s Course Choice program, which allows high school students to shop among public and private course providers, including those that are exclusively online or feature a hybrid of face-to-face and distance instruction. Unbundling individual courses in this way ensures students have the flexibility to develop a personalized education and providers have the freedom to specialize.

Education savings accounts (ESAs) allow parents to withdraw their children from public district or charter schools and receive a deposit of public funds into government-authorized savings accounts. Those funds can cover private school tuition and fees, online learning programs, private tutoring, educational therapies, college course costs, and other higher education expenses.

Because some ESA programs permit parents to “roll over” unused funds to use towards college tuition at a later time, this new type of school choice program encourages parents to be price-sensitive in the education marketplace. And because parents can spend the education funds made available for their child in a piecemeal fashion, this type of policy incentivizes providers to think creatively about new ways to structure teaching and learning.

School choice policy should also consider ways to encourage expansion and replication of effective and popular schools. States could step in by offering school expansion loans with competitive interest rates or dedicated facilities funding. In a similar vein, school leaders should be empowered to leverage new social financial models that have emerged from partnerships between the public, non-profit, and private sectors. These include social impact bonds, innovation funds, and impact investing. Such tools offer a new mechanism for grant making that should be exploited to encourage the replication of high-performing schools.

Innovating in education can be risky. There are up-front costs to consider that inevitably redirect resources from other purposes, and reform leaders risk losing political capital if the innovative policies they institute fall flat. Though we have little doubt that teachers, principals, and school leaders in district schools genuinely desire to enact the types of reforms that will benefit students, the traditional incentive structures that have long dominated K–12 education stifle bold action when and where it is needed.

A burst of competitive pressure upends that structure, incentivizing schools to seek out innovation, instead of simply eating their broccoli. THAT should be the new normal.

*Opinions expressed by our guest bloggers are their own and do not necessarily reflect those of EdChoice.