The K-12 Financial Cliff: What States Could Face If Students Switch Schooling Sectors

Much attention has rightly been paid to American families across the nation who continue to help their children learn at home during this pandemic. When will schools go back? Will they even go back in the fall, and what will that look like?

Our economy—with one in five American workers currently out of a job—has similarly dominated national news. And it’s not good news, either.

We want to take a moment to focus on the intersection of these two stories, specifically what might happen if students currently enrolled in private schools are no longer able to attend those schools due to the financial hardship caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

This could happen because families are no longer able to afford tuition or because schools see a drop in the charitable giving that supports their ability to offer scholarships to students in need. (For reference, the Great Recession just over a decade ago decreased private school enrollment in “high-severity” metropolitan areas by roughly 40 percent.)

Either way, students who currently are in private schools largely supported by family sacrifice, private dollars and publicly funded scholarships could suddenly wind up back in the traditional public system.

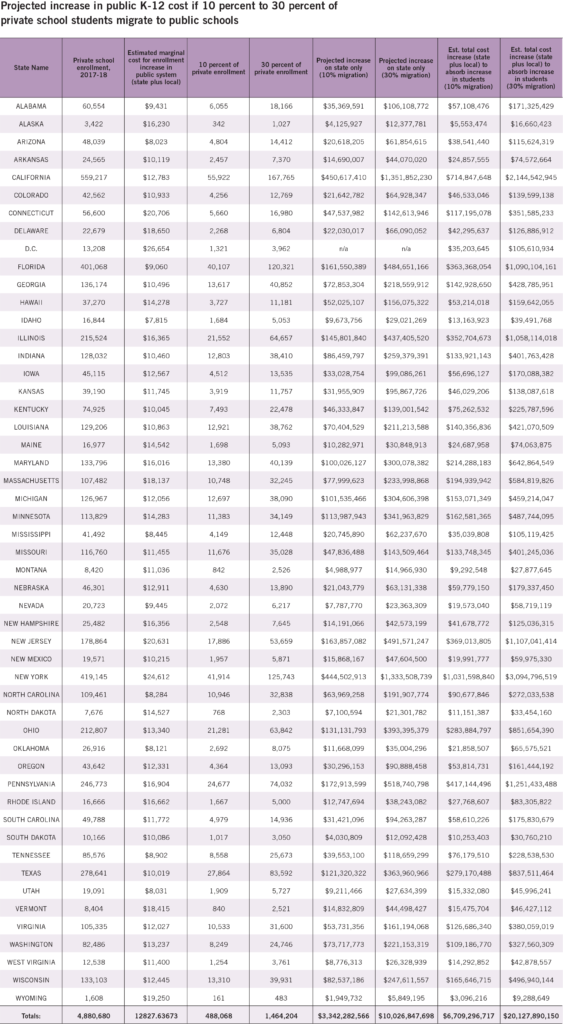

We dug into the state-by-state numbers to find out how many students attend private schools and what would happen to state and local budgets if a percentage of those students wind up back in the public system. We used federally available data for state and local per-pupil funding in each state to make our calculations. The picture is not rosy for states or districts.

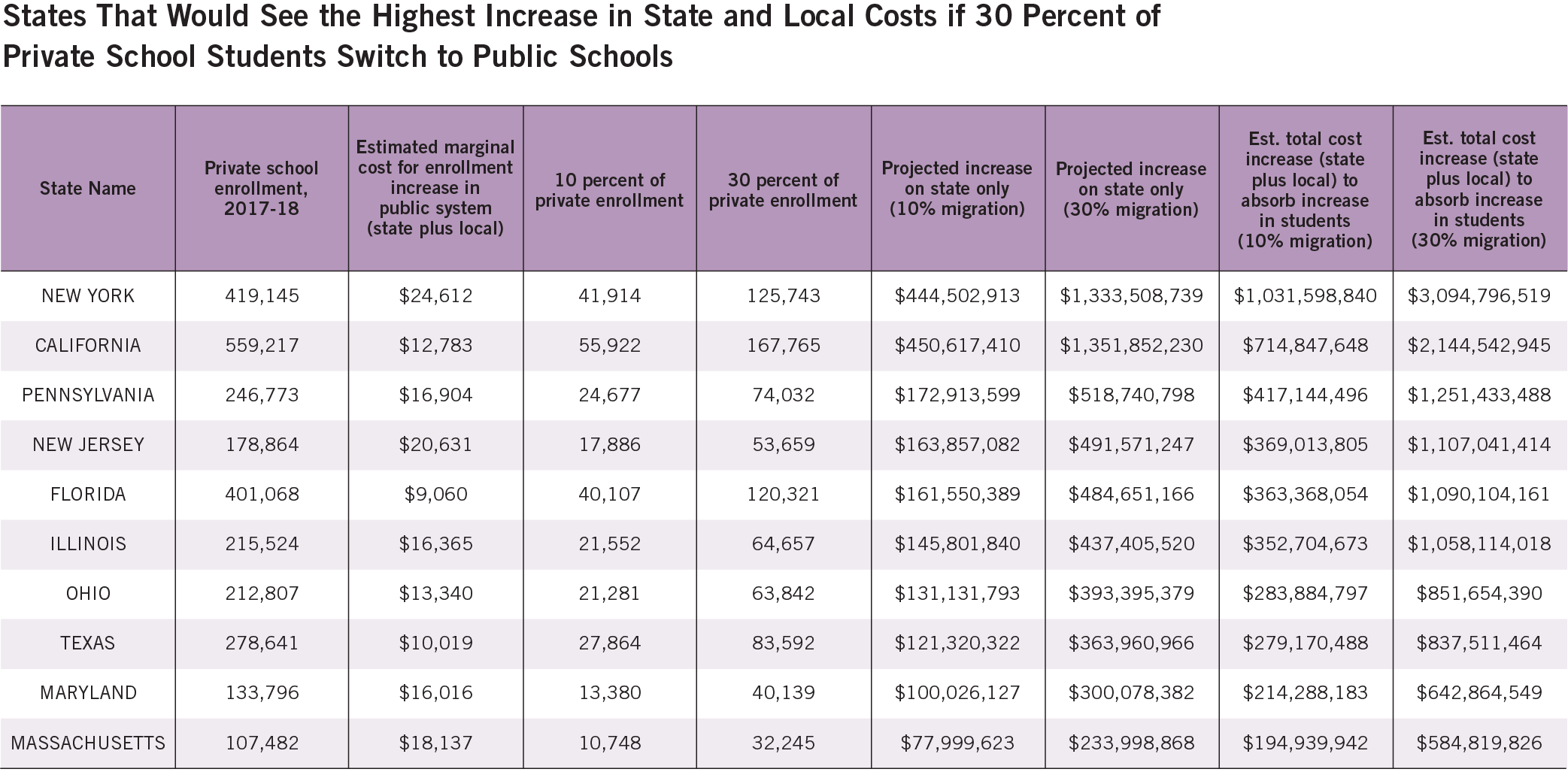

If only 10 percent of private school students return to the public system, the combined state and local cost would be $6.7 billion, with $3.3 billion falling to the states. If 30 percent of private school students have to be reabsorbed into the public system, that cost jumps to roughly $20 billion, with states responsible for just over $10 billion.

Given that state leaders already are preparing for significantly reduced revenue and a strained economic recovery post-pandemic, these numbers are staggering and should worry every education advocate in America.

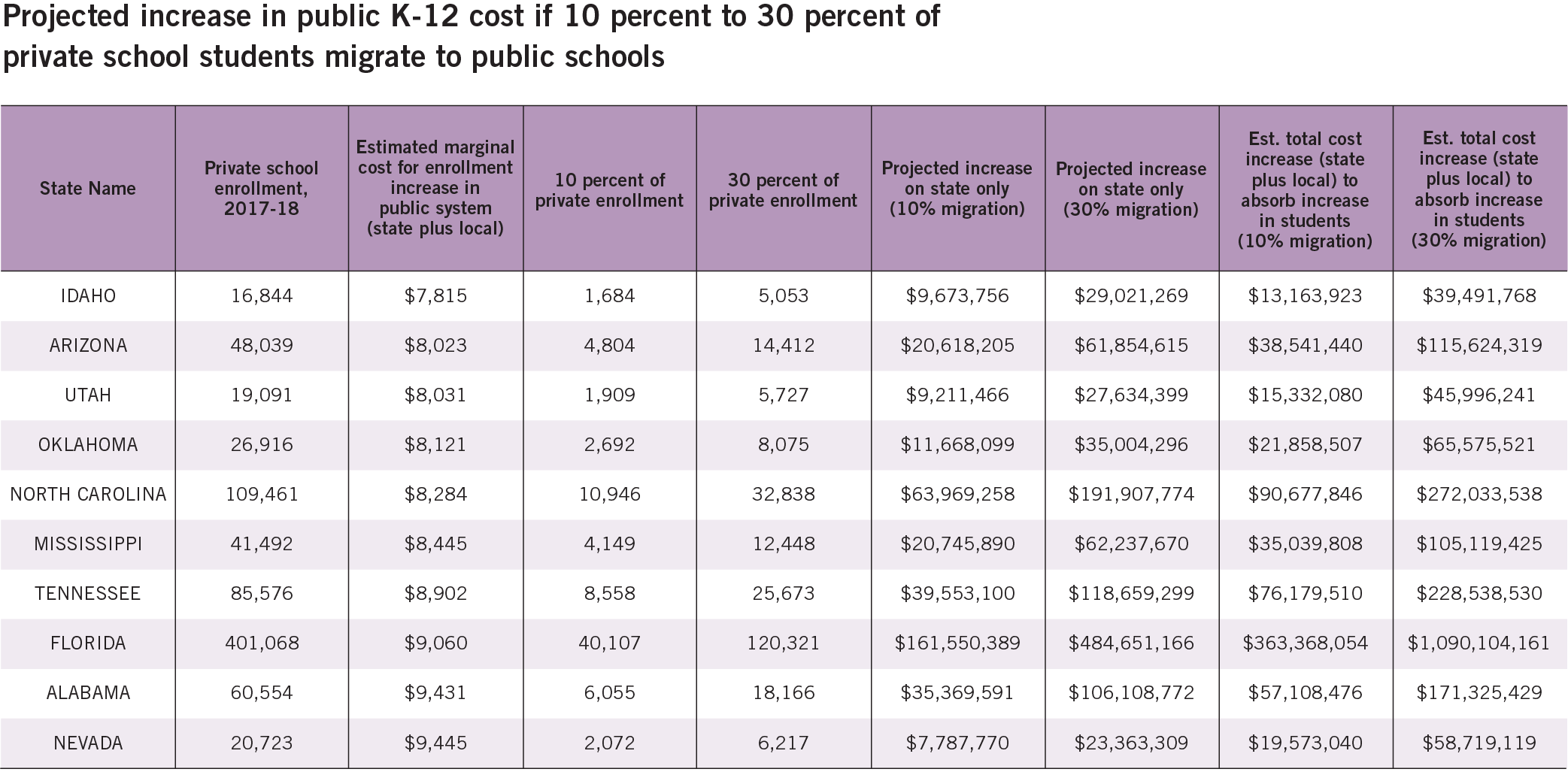

Average per-pupil state and local funding for K-12 education runs the gamut from a tick under $8,000 in Idaho to more than $20,000 per student in New Jersey, Connecticut, New York and Washington, D.C.

It’s true that states with higher per-pupil funding would have to come up with more funding to cover a shift of students from private to public education, but states that fund students at lower levels could still have to find hundreds of millions in new revenue. That’s because the share of private school students varies from state to state.

Top Ten States with the Highest Burden Under 10 and 30 Models

Effect on States with the Lowest Per Pupil Funding in the Nation

Some of these states might be better positioned than others to absorb these additional costs in normal times, but all states currently face financial uncertainty in light of COVID-19. (We will address the additional threat posed by the looming pension crisis, which grows more severe in times of economic instability, in a future blog post. Public pensions have lost $1 trillion as a result of COVID-19.)

These data points should give any policymaker pause for fiscal reasons, but there’s another, perhaps even more compelling, reason to consider the effect of this pandemic on K-12 education: consistency.

Our lives have been disrupted and, in many cases, upended in ways we could not have imagined even six months ago. No matter what schooling type they attend, most children haven’t seen their friends face-to-face in weeks, and many schools have called off in-person for the duration of this academic year. It remains to be seen whether things will be back to normal by fall.

Choosing a school for a child is a decision not taken lightly. If families are forced to give up their school of choice, that is yet another painful change added to the layers of painful changes our nation has endured since March.

As policymakers look to the future—whether in the next few months or in the next legislative session—we hope they will note the high cost to state and local budgets if students are forced to leave the private schools they have chosen to return to the traditional public system.

We hope, too, that they take into account the very real toll any move between schools takes on students—especially when that move is involuntary. At this moment, it feels like we should do everything in our power to maintain the parts of our lives that can be consistently maintained. Schooling can be one of these areas if policymakers keep all types of K-12 education in their sights as they plan for post-pandemic recovery.