Top Five Questions About Teacher Pay

Teacher pay has made lots of headlines the last couple years, with educators in Illinois and Indiana among the latest to take action to up their salaries.

Because K-12 funding is so complicated, we thought it would be a good time to throw out the Top Five questions we get asked about pay. Some of the answers—we tried to keep them simple—might surprise you.

1. Who sets teacher pay?

K-12 funding comes from a variety of sources—federal, state and local—depending on the state and how its budget and formula are structured. Teachers tend to be employed by their local school districts, which receive funding from those various sources and determine how to spend it.

Teachers protesting their pay have largely rallied at Statehouse buildings, but the elected officials there are only one piece of a much bigger funding puzzle that ultimately ends in the hands of leadership within a particular teacher’s school district. Those are the folks who negotiate contracts, set wages and oversee school-level budgets. Their meetings are often less publicized, and their elections are far less interesting, but they have tremendous control over how much money educators take home each pay period.

2. In places where K-12 funding is on the rise, why don’t districts pay teachers more?

Plenty of states have taken action recently to increase K-12 funding and teacher pay, but a union-backed think tank released a report last year that showed teachers make 20 percent less than other college-educated workers, though some of that gap is made up by health care and pension benefits.

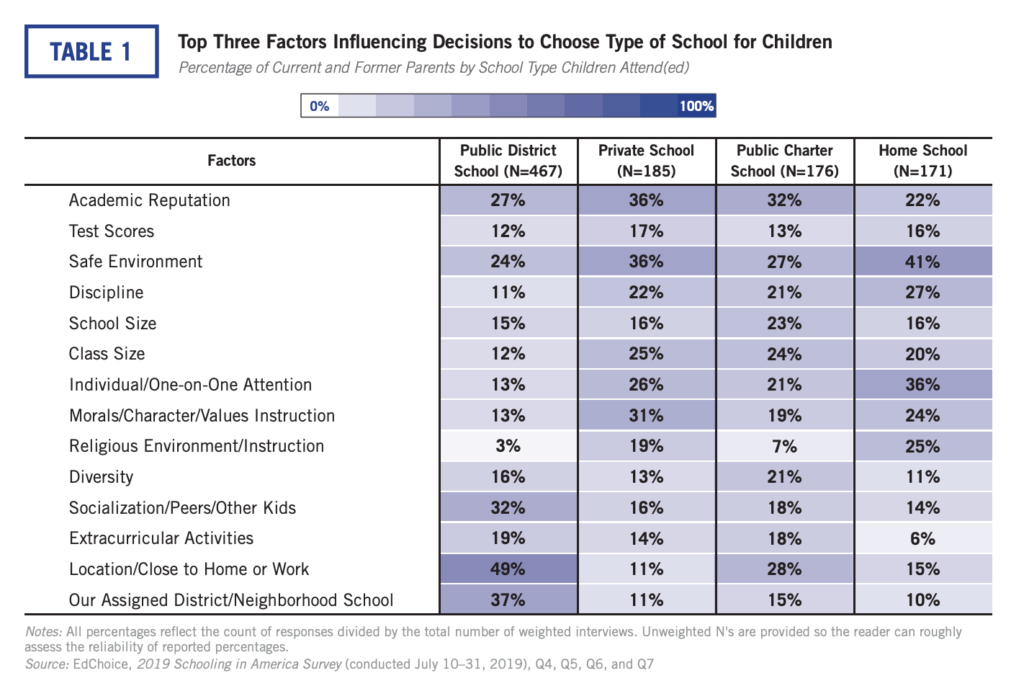

So how have districts been spending their money? Between 1950 and 2015, they hired teachers at a much faster pace than the student population has grown, resulting in smaller class sizes. Research may be mixed on the academic effects of class sizes, but it’s clearly an important issue for parents, especially those who have chosen a private or charter school for their kids:

Here’s the rub: While the number of teachers has grown 2.5 times faster than the student population, the number of non-teachers—including administrators, social workers, counselors, reading and math coaches, janitors, bus drivers, cafeteria workers and curriculum specialists—has increased more than seven times faster than student growth. We call that the staffing surge.

And as public schools hired more and more non-teaching staff, inflation-adjusted salaries for public school teachers fell by 2 percent.

Not only did teachers’ salaries stagnate, but they were also more vulnerable to cuts when school budgets were tightened. During the Great Recession—when the staffing surge was briefly and modestly reversed—school administrators were 1.7 times more likely to fire teachers than they were to fire other administrators or non-teaching staff.

3. Don’t we need non-teachers and support staff, too?

We’re not in the business of picking winners and losers; at the end of the day, it comes down to what districts—and the folks who govern them—set as their priorities. From our vantage point, though, it can be frustrating when school boards and administrators threaten to cut educators in order to get more funding—but then they don’t spend that money increasing teacher pay.

In reality, the people who most directly oversee the money that’s allocated for each district often face little public pressure to spend it on educators because the process of getting the money from Point A to Classroom B is so complicated.

4. So are these protests helping or hurting?

There’s no doubt huge protests in recent years have drawn unprecedented attention to teacher pay and the critical role teachers play in our kids’ lives. That’s a good thing. But we’d again urge caution about where blame is placed. Are there states where K-12 funding has lagged? Yes. But this issue doesn’t start and end with state budgets: It trickles all the way down to each individual school district and how they prioritize teachers and their pay and benefits.

5. What else could teachers be doing to raise awareness—and their salaries?

Ask more questions, especially if someone is trying to put all the blame in one place. K-12 funding comes from federal, state and local sources before winding up at the district and school levels, where even more decision-makers get their chance to allocate it.

Anyone who tells you that only the Governor or state lawmakers or Congress or the U.S. Department of Education are responsible for stagnating teacher pay might be someone who’s part of the reason teacher pay has stagnated.

Are you a teacher? Have you ever tried to figure out the funding formula that leads to your paycheck? Would you be interested in putting together a list of spending priorities that better reflects your vision of K-12 education? We’d love to hear from you at media@edchoice.org.