Unbundling: How K–12 Education Could Do Transportation Differently

As school districts across the country deal with uncertainty about how schools will reopen in the Fall as the COVID-19 lockdown is lifted, many organizations (such as AFT and AEI) have proposed guidelines for education leaders to consider as they pen their plans for reopening. Some of these guidelines include calls for physical distancing, screening measures recommended by the CDC to identify potential cases, and employing protective equipment.

As school leaders choose to follow certain physical distancing protocols in school buildings and classrooms, they also need to consider how those protocols are followed in pupil transportation environments.

The CDC recommends that school buses should seat one student per row and to skip rows to help maintain a healthy environment. Effectuating this recommendation may require larger fleets of school buses, which will also require an increase in bus drivers. Some districts may be able to cope with minimal hassle if buses already operate well under capacity to begin with. Many districts, however, may need to make big changes that could substantially increase the costs of their operations. Other scenarios are possible, of course, including more than one complete run of school buses per day, which also increases transportation costs.

Prior to COVID-19, public K–12 school districts spent more than $25 billion annually on student transportation, or 7 percent of its total spending. An estimated 55 percent of public school students, more than 25 million students, are transported by an estimated 480,000 school buses each day at public expense.

Nationwide, the cost of transporting students on a per-pupil basis, after adjusting for inflation, rose from $657 to $912 between 1998 and 2017, an increase of 40 percent—and these costs may go even higher given social distancing requirements. Table 1 compares the growth in real overall public K–12 spending to growth in real pupil transportation spending. Most states experienced greater rates of growth in pupil transportation spending, with about half of states having pupil transportation spending outpacing overall spending growth by 10 percentage points.

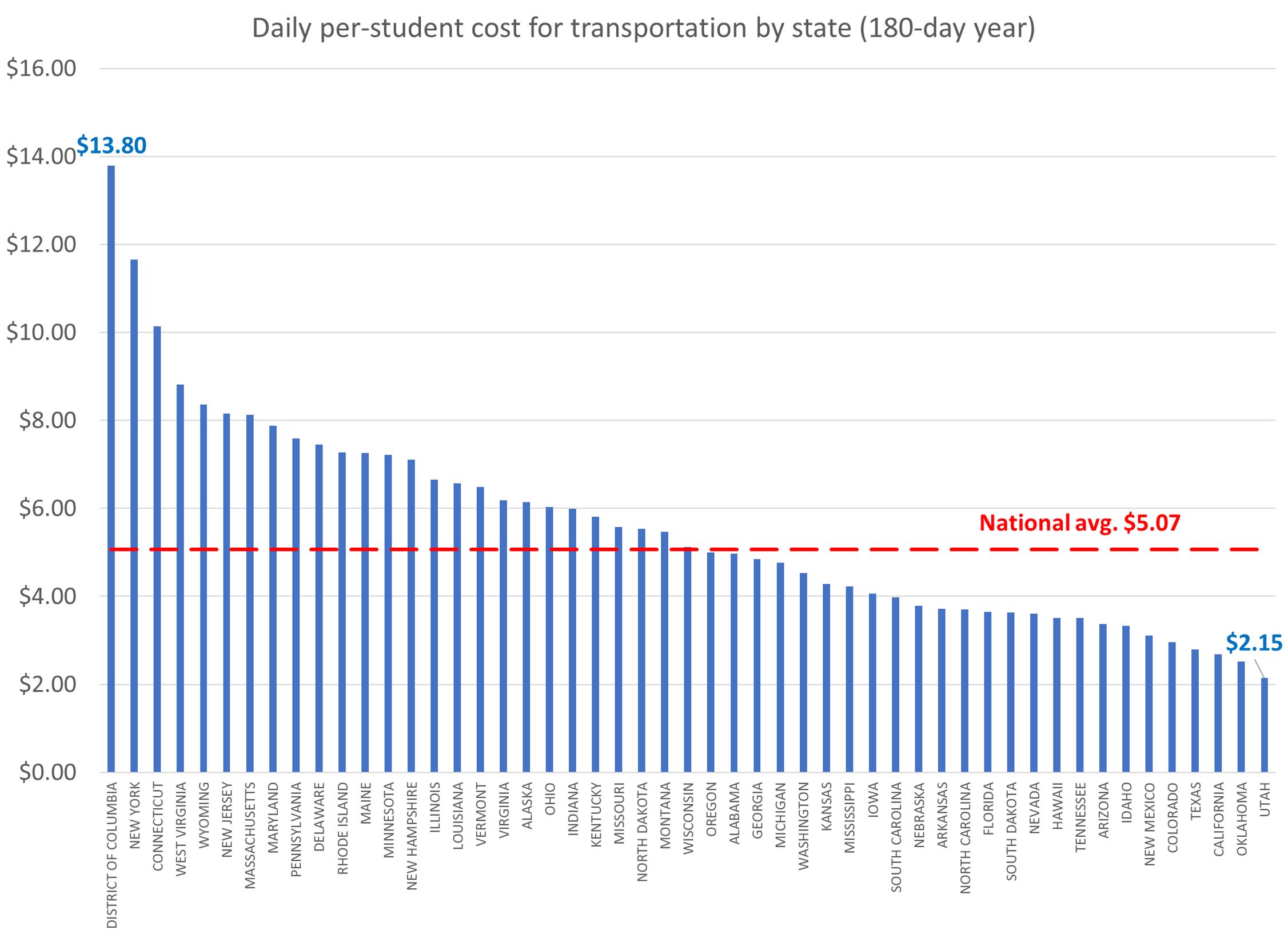

Put another way, the public school system spends a bit more than $5 per student each day on transportation (based on a 180-day school year). As shown below, these costs vary significantly across states—and will also vary within states across school districts.

Twenty-two states plus the District of Columbia spend more than $1,000 per student on pupil transportation. New York and D.C. spend more than $2,000. That’s about $12 and $14 per student each day, respectively. At the other end of the distribution, California, Oklahoma and Utah spend less than $500 per student on transportation, or less than $3 per day for each student it transports.

In a handful of states, such as Hawaii, Ohio and Wyoming, per-student transportation costs more than doubled. Transportation costs in the District of Columbia increased more than 200 percent over this period. In Florida, Idaho and Oklahoma, these costs increased by less than 10 percent.

While per-student transportation costs decreased in New Mexico by 18 percent since 1998, costs for pupil transportation have increased almost everywhere else. In light of all the uncertainty surrounding the effects of the COVID-19 recession and how districts will cope:

• Can policymakers do anything to mitigate the increased fiscal strain that many are predicting, particularly in the area of pupil transportation?

• Are there other providers who might get into the mix who can provide the same level (or better) service?

• Can we alleviate the responsibility of pupil transportation for school administrators, freeing them from this hassle?

Reducing costs and improving the quality of services are two main reasons that districts might consider entering into partnerships with private enterprises. Although nobody really knows the complete extent to which school districts contract out for pupil transportation nationwide, many districts in some states already contract out to private vendors to provide school support services that would otherwise be performed by district workers.

The proportion of school districts that contract out to private vendors varies considerably. According to a 2015 survey of 5 states by the Mackinac Center, for instance, about two-thirds of school districts in Pennsylvania contract with private vendors to provide student transportation while in Georgia less than 2 percent of school districts did the same.

Contracting out to private vendors itself will not guarantee that desired outcomes will be achieved. Here are some recommendations:

• Eliminate costly and unneeded regulations. The fundamental nature of school transportation with the odd hours it requires for workers and the spread of students across large geographic areas make it a challenging market to work in. The tangle of state and federal regulations that place requirements on what buses need to look like and who needs to be driving them bake in a lot of costs. Of course, transportation safety is important for parents – public officials should eliminate regulations and costs without coming at the expense of children’s safety.

• Embrace innovation. Cost pressure can drive innovation, and policy makers and district leaders should embrace it. Startups like Kansas City’s Transportant are using technology to improve bus routing and bus management that can improve the rider experience and drive costs down. Numerous ridesharing platforms have experimented with student transportation, and with some regulatory flexibility and improvement to their systems, could be a solution as well.

• Learn from other states. To lower pupil transportation costs and perhaps provide better service will take some rethinking and new approaches. This great Bellwether Education Partners slide deck lays out a persuasive case that simply contracting out pupil transportation hasn’t been a solution for better service or lower costs. There is a large divergence among states in per-student transportation spending (Figure 1), and the explanation does not seem to be urban vs. rural states. Can high cost states like DC, NY, CT and WV glean any lessons from low-cost states to reduce their own costs?

• Get the processes right for contracts. Some empirical studies such as this one suggest that outsourcing to a private vendor itself will not guarantee the desired outcomes of lowering costs and raising quality. Districts will need to have well-executed processes such as bidding, awarding, and monitoring contracts. This helpful primer from Mackinac includes some useful guidelines for districts that might be considering contracting out school support services.

Pupil transportation may prove to be a tough nut to crack, but public school leaders and state policymakers need to eliminate costly and unneeded regulations and look at innovations like Transportant and ride sharing to see if they can provide better value to taxpayers and more convenience for students and schools. Given the increasing costs and dissatisfaction that many people on both the school and industry sides of the equation are feeling, pupil transportation seems ripe for rethinking and improvement.

Read more from The Unbundling Series:

Five Services Public Education Should Do Differently

Three Ways Public Schools Can Rethink Food Services

A New Way to Approach Teacher Professional Development and Classroom Supplies

Rethinking How We Deliver Remedial Services to Students Who Need Them

Three Policies That Would Improve Schools’ Core Education Services