What New Teen Polling Tells Us About the State of K-12 Education in 2024

Last week, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis signed a new bill banning children under the age of 14 from creating a social media account in the state. This bill, scheduled to take effect in January 2025, aims to “give parents a greater ability to protect their children.” It raises the question, what is the youngest age someone should be in order to access social media?

As coincidence would have it, we asked this exact question, along with many others, in our newest survey of American teenagers.

In partnership with Morning Consult, we at EdChoice surveyed a nationally representative sample of American teenagers, ages 13-18 (N=1,002). The survey was in the field from February 27-March 6, 2024. This is the 8th wave of the teenager survey and the first of 2024. Here are some of the major themes from the report:

Teens’ opinions on social media and cell phones

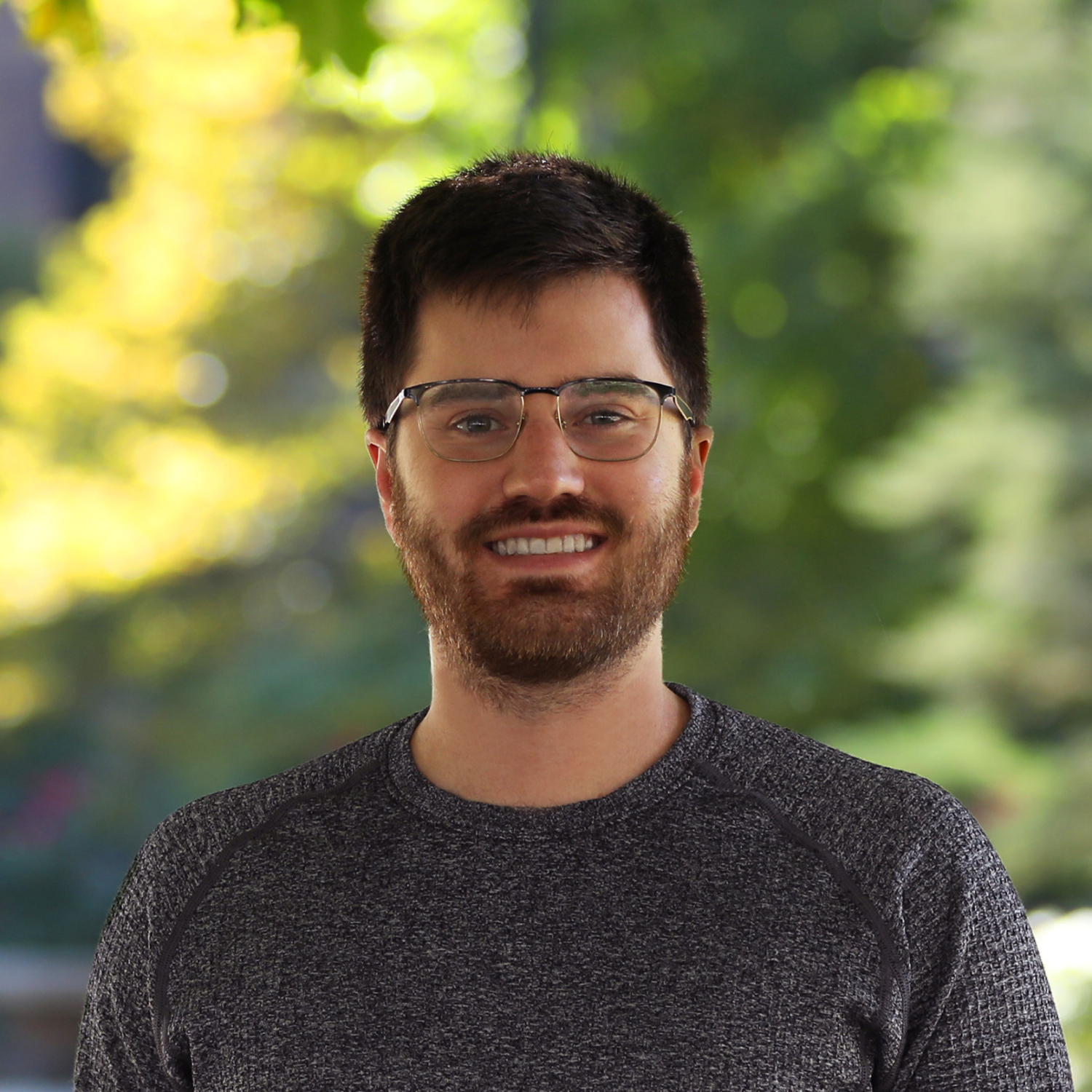

American teens may not be happy with the idea behind the new Florida bill. Thirty-four percent believe that children 12 years old and younger should be able to access social media. Thirty-two percent believe that children should be at least 13, and 35% believe they should be at least 14. This means that in Florida’s case, two-thirds of teens would oppose requiring someone to be at least 14 before accessing social media.

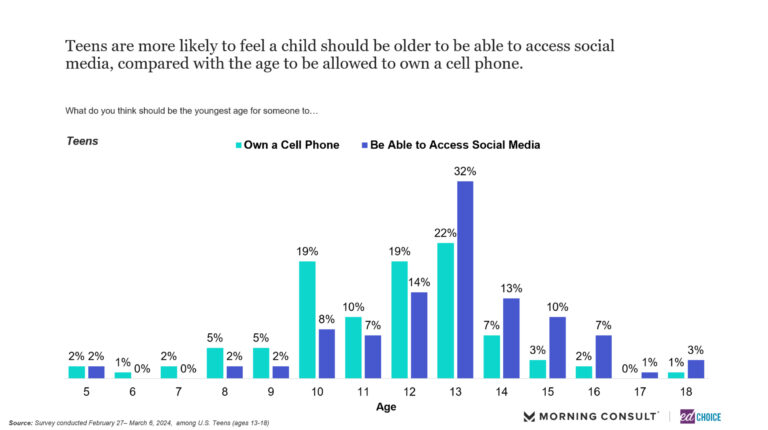

The idea of restricting the use of social media among minors feels connected to several other findings in the report. For example, 74% of teens said they are on social media either “extremely” or “very” often. Coupled with the point that 40% of teens said that social media has had a negative impact on their mental health and self-confidence, the motivation for bills like Florida’s becomes clear.

The idea of restricting the use of social media among minors feels connected to several other findings in the report. For example, 74% of teens said they are on social media either “extremely” or “very” often. Coupled with the point that 40% of teens said that social media has had a negative impact on their mental health and self-confidence, the motivation for bills like Florida’s becomes clear.

In addition to social media, we asked teens about the youngest age someone should be to own a cell phone. Teens were pretty certain, with 83% saying they think someone should be at least 10 years old before owning a cell phone.

The question of cell phones in school has been burning for quite some time. Teens’ views are clear: 91% support cell phones being allowed in school and 65% support the idea of allowing cell phones in the classroom.

Our most recent poll of parents painted a different picture. While 71% of parents supported the idea of students having their cell phone at school, only 38% felt students should be allowed to have cell phones in the classroom.

What’s happening inside the classroom from the eyes of American teenagers?

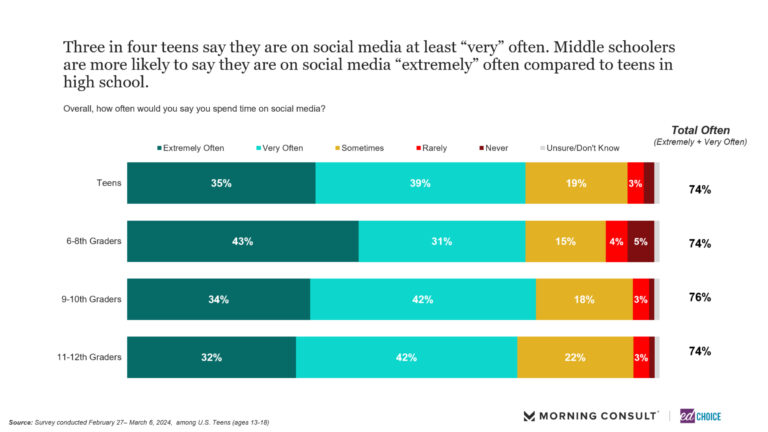

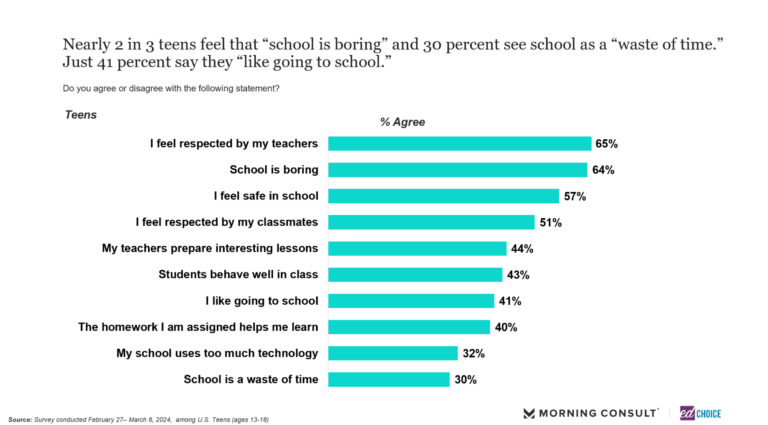

Teenagers did not hold back when asked to share their, along with their classmates’, experiences in school. When asked about school generally, 64% of teens agreed that school is boring. Perhaps worse, only 41% of teens said they like going to school while 30% said that school is a waste of time. They painted a similarly bleak picture of their classmates’ views towards school. Nearly three in four teens said their classmates are bored in class, while 15% of teens said none of their classmates want to be in school. Thinking back to the prevalence of cell phones in the classroom, more than half (55%) of teens said their classmates use their phones inside the classroom.

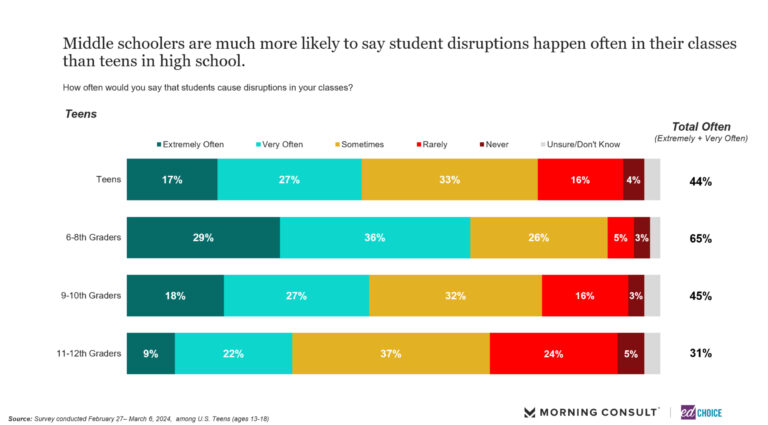

Admittedly, it is not breaking news to learn that teenagers aren’t huge fans of being in school all day. It is fair to ask, though, to what extent does teens’ indifference or boredom impact the classroom? According to teens, 44% say students cause disruptions in their classes either “extremely” or “very” often. The problem is amplified among middle school classrooms, with 65% of middle schoolers reporting students are causing disruptions in their classes either “extremely” or “very” often. Asked about the frequency of student misbehaviors in class, roughly one-third of teens feel student misbehaviors are “a lot” or “a little” more frequent compared to this time last school year. Middle schoolers stand out again here, with nearly half (48%) feeling as though student misbehaviors are happening more frequently than this time last school year.

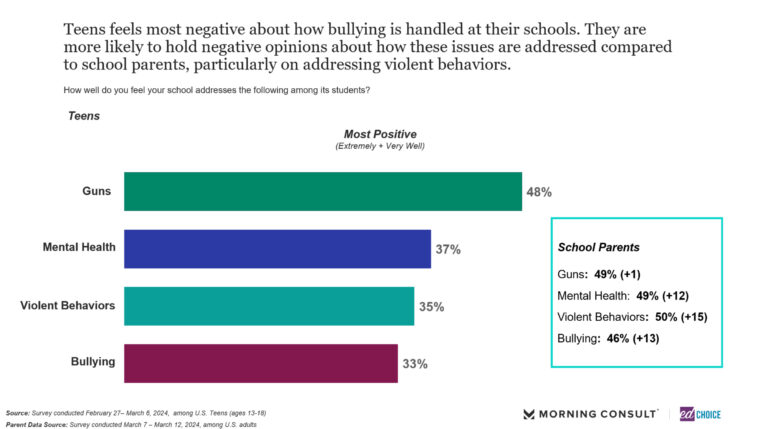

Assuming the idea that student disruptions and misbehaviors are happening more frequently is accurate, how much of the blame falls on the school itself? What are some ways schools can improve to help foster a better learning environment for students? Well, according to teens, addressing bullying and violent behaviors would be a good place to start. Only about a third of teens feel their school is doing well addressing problems like bullying (33%) and violent behaviors (35%).

The same can be said for mental health, with only 37% of teens feeling their school is addressing the issue well. Mental health, both in and out of school, is an area of concern for teens. We ask teens to rate how they feel about various aspects of their life, including their academics, health, and relationships. Out of all these areas, teens are least positive about mental health, with only 34% saying that they feel satisfied with their own mental health. Correspondingly, teens feel least supported in their mental health needs (64%), compared to support they receive for academics (83%) or thinking about the future (78%).

To what extent are absenteeism and school safety connected?

Perhaps the most illuminating finding, though, comes from the previously discussed question examining teens’ thoughts towards their school generally. Only, yes only, 57% of teens feel safe in school! A finding as striking as it is relevant to our discussion, it is no wonder teens are not quick to sing their schools’ praises for their handling of issues like bullying and violent behaviors. Safety in school is undoubtedly one of, if not the top priority for parents as well as the school itself, yet nearly half of teens are questioning their safety while at school. Obtaining a quality education is going to be a much larger mountain to climb if the students are worried about their safety.

Achieving a quality education is also quite difficult if the student is not present in class. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, K-12 absenteeism has skyrocketed. U.S. Department of Education data shows that 30% of students were chronically absent in the 2021-22 school year—and only minor improvements since. To make matters worse, parents underestimate how often their kids miss school. According to new data from the USC Understanding America Study, only 15% of caretakers say that their child missed more than six days of school in the fall 2023 semester. In our March poll, a quarter of teens reported missing more than 10 days of school over the course of the school year, and 32% of teens said that their friends had been absent from school for more than 10 days this year. This gap between teens’ self-reported absences and parents’ estimates may reveal that parents are not fully aware of their kids’ school attendance—a concerning possibility as schools try to reduce this surge of absenteeism.

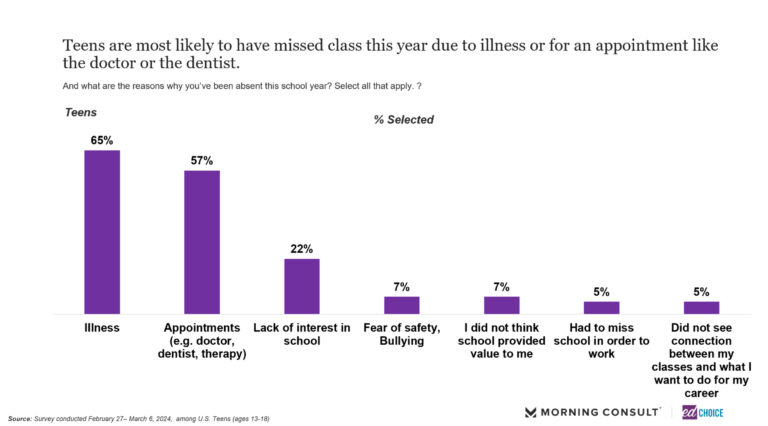

While this recent surge of absenteeism is undoubtedly a major problem for both families and schools, the root causes are not entirely clear. In the report, teens were most likely to list illness (65%) or some kind of appointment (57%) as the reasons for being absent from school. Teens also listed reasons such as lack of interest in school (22%) or fear of safety, bullying (7%) to explain missing school.

There is a lot to unpack here, surely, but more than one in five teens citing a lack of interest in school as their reason for being absent is startling. Missing school because of illness or a dentist’s appointment feels relatively customary. On the other hand, skipping school due to a lack of interest or feeling unsafe is much more problematic. New data and research are desperately needed to better understand what is driving the higher rates of absenteeism. Until then, schools have plenty of areas to improve upon.