Why the Fuss Over School Choice and “Certified” Teachers is Overrated

Opponents of educational choice worry that empowering parents and students to attend private schools will lead to a Wild West of schools wrought with teachers who lack “certification,” a puzzling position to take considering public schools are increasing their employment of “uncertified” teachers.

Take Oklahoma as one example. With the passage of Senate Bill 498 last month, the Oklahoma legislature gave the state’s public education system much-needed flexibility during what the state Department of Education described as “an ever escalating teacher shortage crisis.” The bill allows retired teachers, including those who are no longer up to date with their state certifications, to return to teaching without a limit on their earnings for three years. The previous limit for these and other “emergency certified teachers” had been $15,000, and the state issued 1,160 such certificates for the past school year. That number has increased 35-fold in five years.

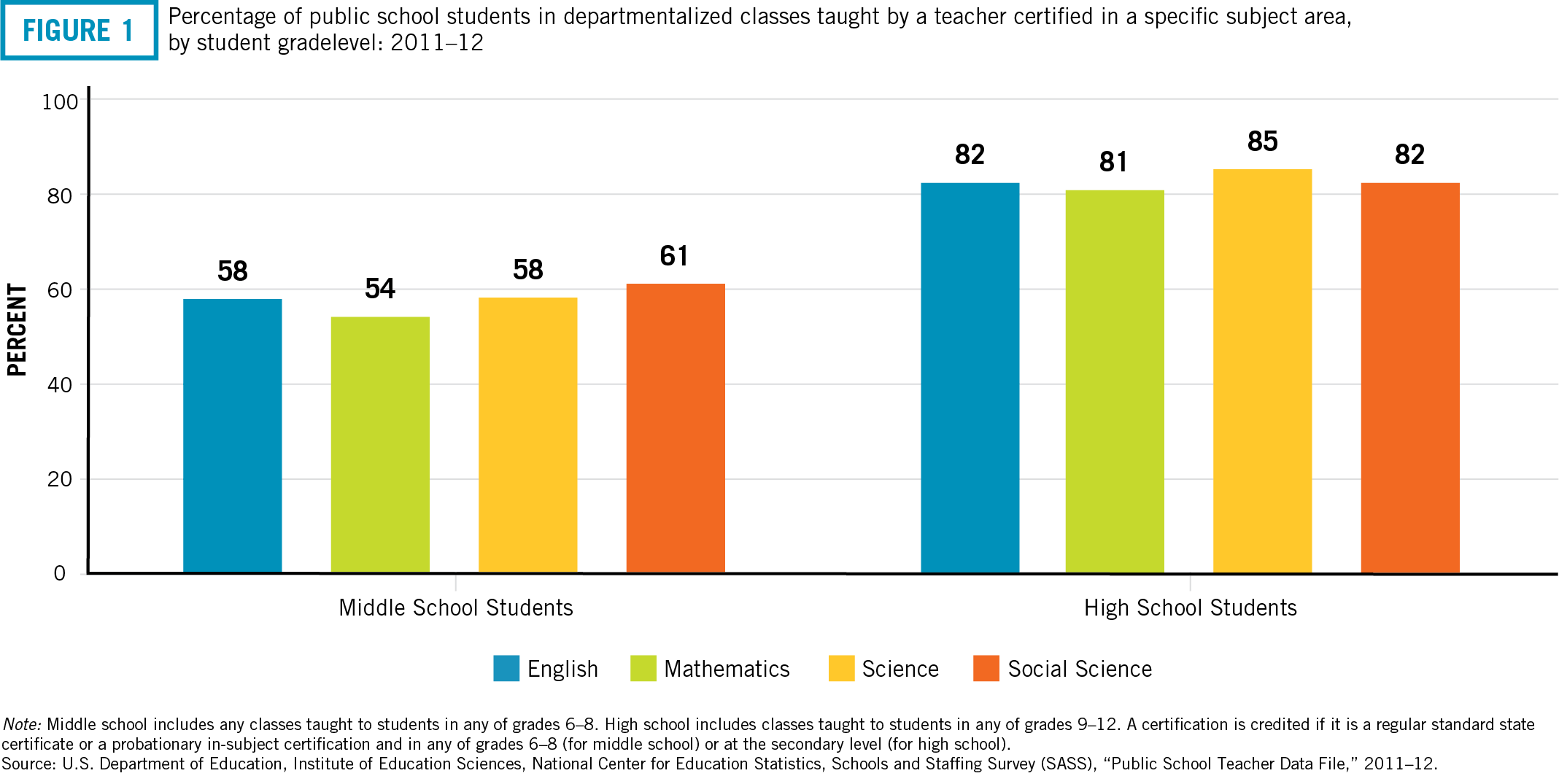

Public schools employing teachers who aren’t fully certified isn’t isolated to one or two states, either. The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) found not all public school teachers are state-certified in a recent study of K–12 public school students. NCES also reported that nearly half of middle school students in departmentalized classes—those with specialization in a specific subject area—are not taught by a teacher licensed in that specific subject, and roughly one out of five high school students is in a similar situation.

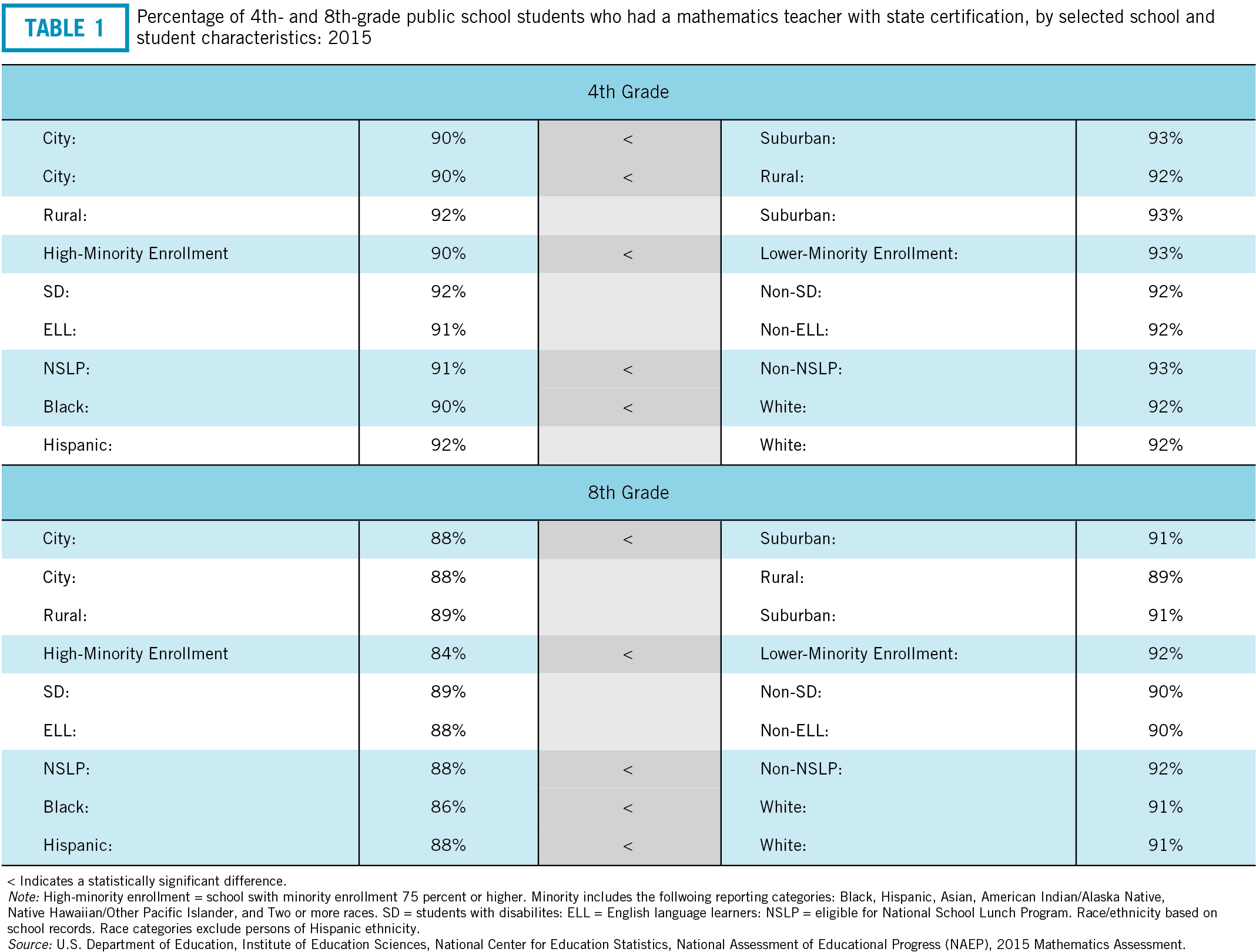

Furthermore, students in urban district schools had fully certified teachers in their classrooms at lower rates than suburban students. Students with special needs had certified teachers at lower rates than students without special needs. And English language learners had them at lower rates than native English speakers. When measuring the fourth and eighth grades, NCES reported that the percentage of students who had math teachers with state certification was lower for students eligible for free or reduced-price lunch than for noneligible students and lower for black students than for white students.

Though this discontinuity could seem alarming on its surface, the rigorous evidence on teacher certification effectiveness is mixed at best.

Kane, Rockoff and Staiger found that certification had small effects, if any, on student performance. On the other hand, they found early career classroom performance was a greater determinant of a teacher’s future effectiveness than their certification status. Goldhaber and Brewer found students taught by math teachers with emergency credentials do no worse than those taught by standard-certified teachers.

Credentialed teachers are often—and understandably—the staunchest defenders of mandatory teacher certification. But not all teachers benefit from mandatory certification, and the practice can make entry to and pay for the profession quite rigid. Nobel-laureate economist Milton Friedman, father of our organization’s intellectual legacy, summarized the issue best:

“With respect to teachers’ salaries, the major problem is not that they are too low on the average—they may well be too high on the average—but they are too uniform and rigid. Poor teachers are grossly overpaid and good teachers grossly underpaid. Salary schedules tend to be uniform and determined far more by seniority, degrees received, and teaching certificates acquired than by merit.

Those words were written back in 1962. Since that time, we know from publicly available data and our original research that real expenditures on K–12 education have risen, and public school teachers have seen their real salaries fall while administrators and other non-teachers are hired at a far higher rate.

It’s little wonder that there’s a growing conversation nationally about the shortage of teachers and how to get more college students to enter the profession.

We recently interviewed Stanton Skerjanec, a first-year charter school teacher in Fort Collins, Colo., who hit the nail on the head:

“I think most teachers (and I don’t want to sound naive about this), but I think most teachers want to just teach. They want to do their job. Of course, there are individuals and groups that are the more unionist type that just want to maintain a sort of status quo, but by and large, they want to do their job. That said, they may think that they can’t do their job, or that they’ll be hindered in their job, if we go to a new, more free choice system.

“Now, one of the common things I hear with non-charter teachers is: The poor get left behind. The demographically underprivileged get left behind in this system, that we have no guarantees with it. And there are always risks of failure. That, we need to acknowledge. There’s always risk of failure. But I always ask them, ‘Do you want to risk a better future, or do you want to maintain a status quo that has almost no future in sight?’ That’s where you have to bridge the common ground saying that we want to enable teachers to teach. We don’t want to burden them with either a bureaucratic state or some status quo that isn’t going anywhere.

Yet policymakers continue to burden the teaching profession and its practitioners with regulations and requirements that doubtless turn many subject matter experts away from sharing their knowledge with young minds.

Perhaps now is the time to engage in a broader conversation about licensing that places the emphasis not on technocratic accountability but on flexibility for students, schools and, most importantly, educators.